Sugar and Death: The Phenomenon of Baccarat Rouge 540

A deep dive into the most world's most pervasive perfume

It smells like wealth; it smells like heaven; it smells like latex gloves; it smells like a dentist’s office. It smells like luxury; it smells like fairy floss; it smells like burnt plastic; it smells like iodine. It costs $730AUD for 200ml, and yet remains a bestseller. Its short, square bottle with the gold-and-ruby label glimmers like a jewel box on the perfume shelves of influencers and celebrities. Its success has made its creator the famous perfumer in the world and landed him one of the most prestigious roles in the fragrance industry at Dior.

If you live in the hinterland of any city on Earth, you have smelled this perfume. If the algorithm of your news feed or TikTok has decided you’re interested in perfume, you have heard people talking about it. The overpowering medicinal-sweet smell that seems as if it would be cast in jewel tones if it were visible, that never ending scent that finds every corner and lingers there for days; in an era of perfume that is defined by clearly legible notes, it is completely abstract.

A spectre is haunting the world’s shopping centres: the spectre of Baccarat Rouge 540.

Fragrance culture is currently going through a metamorphosis, those tense and fraught stages between forms, and no perfume encapsulates this better than Baccarat Rouge 540. This perfume is at the heart of the niche explosion, the rising popularity of unisex scents, perfume cloning, influencer culture, and the juggernaut that is “perfumetok”. Baccarat Rouge 540 - lovingly called Baccarat by its fans - is the first great viral scent of the TikTok era, it has already changed the way we think about and talk about perfume.

Baccarat’s popularity warrants a deeper analysis of how it came to dominate the fragrance world and land on bestseller lists next to the giants of the industry like Chanel and Dior. Baccarat has immense value to perfume commercially, but does it have any value artistically? And though this is one of the rare perfumes that transcends fragrance culture to become iconic in the mainstream, what does its immense popularity mean for fragrance trends in the future?

The story of Baccarat Rouge 540 and its creator, Francis Kurkdjian, are atypical in modern perfume. Maison Francis Kurkdjian (MFK) as a brand is achingly aware of this, and markets itself on exceptionality. The success of Baccarat has singlehandedly propelled the brand from the fare of fragrance fanatics into the mainstream. It can now be considered one of the great houses of niche.

Niche perfume loosely refers to any perfume brand whose major selling product is perfume: contrast to designer perfume, which is often a companion product to fashion or jewellery companies. Niche perfume has become dominant in the fragrance market in the past twenty years. It includes brands such as Byredo, Le Labo, Editions de parfums by Frederic Malle, and Parfums de Marly.

Another important signifier of niche perfume is that the people who run the company don’t make the perfumes - much like designer houses, niche companies follow the traditional avenue of perfume creation, sending out briefs to which the fragrance oil houses, also known as Big Perfume (Givaudan, IFF, Symrise, and Firmenich) compete to win. This is in contrast with artisan perfume, which are usually small batch independent perfumers running their own shop and making the perfumes.

It is an unspoken law that if a niche company finds enough success, it will be bought out by one of the major beauty conglomerates (L’oreal, Estee Lauder, Unilever, LVMH, and increasingly Puig). One could posit that the goal of every niche brand is to be acquired by the giants of the industry.

A niche brand can’t rely on legacy like Chanel or Dior - one would think this means the actual perfumes have more pressure to be good, but instead they have more pressure to be unique. With niche, the bottle matters, the marketing matters, the influencer collaborations matter. The perfumes are loud and their sillage is eternal.

Into this landscape, Maison Francis Kurkdjian was launched in 2009. It is the collaborative brain child of Kurkdjian and CEO Marc Chaya. Immediately we see that this brand is exceptional on the niche landscape - its perfumes are made by one perfumer, and the entire house is named after him. This may be common in fashion but it is incredibly rare in perfume as the industry suffers from a cloak and dagger tendency to keep its perfumers hidden, chained to the desks of Givaudan and Symrise while brands pretend that their perfumes have been conjured out of thin air.

There is movement both within the industry and by perfume obsessives online to make the industry more transparent, but it is slow and frustrating work. This is the big sell of MFK, the it factor that makes them unique - a perfume house set up in the artisan style but at niche scale. It’s a business model that would have only worked for one perfumer, and one alone.

If there is a perfumer who was going to become a household name, it was always going to be Francis Kurkdjian. Famous in the world of perfume since he created Le Male (Jean Paul Gaultier, 1995) fresh out of ISIPCA (Institut supérieur international du parfum, de la cosmétique et de l'aromatique alimentaire) at 24¹, he quickly built a roster of releases against his name that would impress even the most staunch French perfume traditionalist: Green Tea (Elizabeth Arden, 1999), Narciso Rodriguez For Her (Narciso Rodriguez, 2003), Eau Noire (Dior, 2004), Rose Barbare (Guerlain, 2005), and Tihota (Indult, 2006).

Kurkdjian’s career established him as the go-to perfumer for avant-garde fashion houses, art installations, and bespoke perfume collaborations. His work has included creating the ‘scent of money’ for Sophie Calle, and creating an olfactory element for events at the Villa Medici and the Palace of Versailles. Kurkdjian is French-Armenian and created a new range for the iconic Papier d’Armenie scented papers. This consulting work would continue after he and Chaya established Maison Francis Kurkdjian in 2009.

Kurkdjian’s style is described on his website as ‘guided by enchanting yet precise codes: purity, sophistication, timelessness and the boldness of a classicism reinvented.’² While it is tempting to dismiss this as typical perfume industry faff, the crucial phrase here is ‘classicism reinvented’. Kurkdjian’s style is revolving in the small world of French perfume legacy that lingers in the air at ISIPCA and Givaudan and Firmenich.

Perfumers who self describe as having a classical style (Jean-Claude Ellena is another) worship at the altar of Roudnitska and Jean Carles, and this can be smelled in everything that they make. When you are constantly trying to reinvigorate classic structures in perfume, the same thing that everyone else has been doing for a hundred years, there’s only so many ways to sing the same song. These perfumers make pleasant perfume; sophisticated perfume - they don’t make innovative perfume; exciting perfume.

To perfume agnostics I give the analogue that Francis Kurkdjian is the Leonardo DiCaprio of the fragrance world: he became very famous very young and has since curated a reputation for quality. Like Leo, when you look back at the actual work it may be a reputation that is not exactly deserved, but it is there nonetheless.

Quality, classicism, sophistication and luxury: these are all words that define the portfolio of perfumes at Maison Francis Kurkdjian. Every perfume of Kurkdjian’s could be considered classicism reinvented…. except one.

Abstraction

“As always, I started by finding the name, because a great story often leads to a great perfume.” - Francis Kurkdjian

Before it was Baccarat Rouge 540, it was Rouge 540 Baccarat.

The name, as Kurkdjian tells it, comes from the temperature that Baccarat heats glass to reach the iconic ruby red shade they are known for. The year was 2014 and Baccarat, a glassware company, commissioned Kurkdjian to create them a custom scent for their 250th anniversary.

The appeal of the brief for any perfumer is apparent: in the great trailblazing era of perfume in the 1920’s when every perfume had a unique bottle and those bottles were handmade, Baccarat was the glass maker of choice. Their prestige in the world of perfume can only be compared to Lalique, and even then Lalique did not make the original bottles for Mitsouko (Guerlain, 1919). To make a perfume for Baccarat would be an impressive line on the resume for any perfumer.

Luckily for us, people want to know the story of Baccarat’s creation and Kurkdjian is more than willing to tell it. From various interviews he has done about the scent, ranging from when it was first released in limited form to after it had gone viral, we can piece together the structure and creative process of the perfume.

“The symbol of Baccarat is the red crystal, which is made out of gold and crystal and it is about the alchemy of the gold infusion which becomes red at 546 degrees. The resulting crystal is very heavy but has more clarity, more density than glass. So I wanted to translate that idea of clarity, of density. It’s powerful without being heavy. It’s sweet, there is a yumminess, but it’s not sickening ... I am not working with ingredients like vanillas and musks, because they are very thick and heavy. I’m only working with very clear materials and that’s why [it appeals so much to everybody].” - Kurkdjian³

The Maison Francis Kurkdjian website lists only four ‘ingredients’ for Baccarat Rouge 540: Hedione, Ambroxan, Cedar, and Saffron.⁴

Fragrantica, which lists notes by a user generate aggregate vote system, lists: Saffron, Jasmine, Amberwood, Ambergris, Fir Resin and Cedar.⁵

This feels like a short notes list, but it is specifically designed to be so, as Kurkdjian says:

“Rouge 540 had a short recipe. If it were a painting, it would be more like a Rothko than a Seurat or a Renoir: fewer colors, but just as much emotional resonance. I didn't want too many ingredients, only those which were essential to the formula” - Kurkdjian⁶

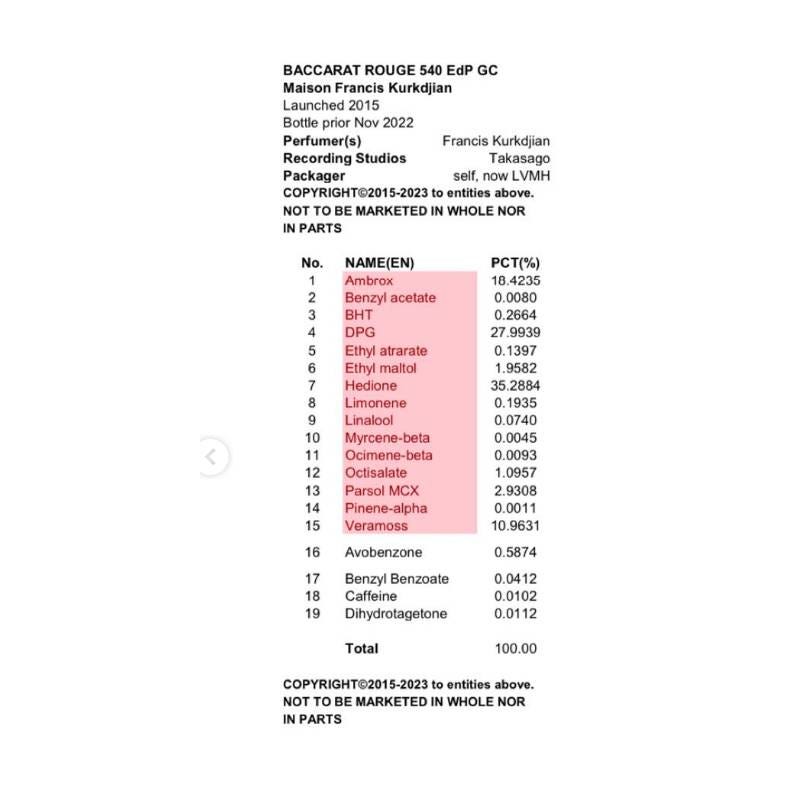

A post on @fragrance.drama, an advocate for transparency in the fragrance industry that publishes gas chromatography reports and analysis on popular perfumes, posted a comparison between Baccarat and Cloud (Ariana Grande, 2016), that does much to lift the veil on what is going on in this perfume. The data, as the caption on the original post states, is raw and not a genuine formula reconstitution:

In regards to fragrance formulas, this is still a stunningly short list - formulas can have over a hundred line results, as viewed on this analysis of Chanel N⁰5 also from @fragrance.drama. Using larger quantities of a smaller amount of ingredients is a bold and risky way to make perfume. Overdosing ingredients can lead to nose fatigue or worse, consumer rejection of the scent.

But overdose, as Kurkdjian states, was always the plan:

INTERVIWER: Tell me about Baccarat Rouge 540.

KURKDJIAN: It’s an amazing fragrance, I think. We’ll see, but I think it’s one of my masterpieces.

INTERVIEWER: Why?

KURKDJIAN: The way it smells. How people respond to it. The formula. The overdose of everything. And it’s only synthetic molecules. I put in orange and tagetes and a few naturals right at the very end, but otherwise it’s synthetic. There’s a synthetic oakmoss, veltol and Ambroxan and hedione. It’s a Jean Carles formulation. You start with two ingredients. You balance them. Then you add a third one. You balance the whole.⁷

Though there can be much unneeded mystery surrounding fragrance marketing, the chemical compound lists of a formula are only half the story and accord or note lists are the other: the formula lists the ingredients that the perfumer uses, and the notes list the product that they have intended to make. A balance between the two is where we can find a deeper understanding of this perfume.

How to describe the scent of Baccarat Rouge? It is a perfume for which comparatives to other perfumes are useless, because Baccarat is a masterclass in abstract perfumery.

Abstraction is the opposite of defined in the way that vagueness is the opposite of specificity. Instead of trying to evoke jasmine, an abstract perfume will diffuse the characteristics of a flower so that no one particular note comes to the fore. The most famous of all abstract perfumes is the most famous perfume, Chanel N⁰5 (Chanel, 1921), which is indescribable if you have not smelled it and unforgettable if you have. Abstract perfumery may have less risk by avoiding imitation - people know what a rose smells like, so if you are trying to imitate that and get it wrong, you’re toast - but when you sail into uncharted waters it can be a gamble that the consumer will want to come with you.

In an era where definition rules in perfume - the note is in the name and sets an expectation so you know exactly how a perfume called Lime, Basil and Mandarin (Jo Malone, 1999) is meant to smell - an abstract perfume is the opposite of that. Abstract perfumery does not smell of anything distinct in nature, and so it only smells of itself.

An abstract perfume holds its throat to the dagger. It is helpful to know the components of an abstract perfume in order to piece together the dots of its creation, so let us describe the elements of Baccarat to piece together the whole.

TAGETES

In the words of its creator Baccarat is entirely synthetic bar some notes of citrus and tagetes (marigold) in the opening. This is not a perfume of gradually unfolding layers - everything is there and screaming at you from the first note to the long, long drydown. Thus these opening notes are lost in the fury of the first spray - they give the scent some lift and brightness but are not there to do the same job as the fruity top notes of a designer department store perfume, the siren’s bait to lure you in and kill. Perfumers will often try to add at least some natural ingredients to a perfume formula because their complexity can confuse a chromatographic result, which may also explain tagetes’ presence here.

JASMINE

Naming jasmine as a note when the perfume really contains hedione is one of the artful lies we’ve all agreed to simply let perfume companies get away with. Hedione is a synthetic ingredient with a own long and fascinating history - it is perhaps the most ubiquitous synthetic in modern perfumery. When hedione was discovered in the 1950’s it changed the way perfumes were constructed. It’s still in use today because the lightness and floralcy it gives perfume is hard to replicate - and because it smells really, really good. There are many components to the scent of a flower: the greenness of the stem, the airy and slightly sweet scent of the bud, and the air of decay that sits behind it all like a time bomb, growing stronger as the flowers nears its end. Hedione captures that moment of a flower in its fullest bloom, sweet and light and sunkissed. It is this brightness that hedione brings to Baccarat, a sense of air and space conveyed through the impression of a flower. Hedione will also enhance and lighten most other notes - hence we see in the data pull that it is the biggest component of Baccarat by a wide margin.

CEDAR

Saying a perfume has a woody note is about as useful as pointing out that a hand has a thumb - most of them do and there’s usually something wrong if they don’t. The thumb of Baccarat is Virginia cedar. It’s a woody note that smells of pencil shavings, sharp and crisp but also a little metallic. You can taste this note in the back of your mouth; it’s dry and scratchy, adding to the airiness of the perfume because it doesn’t have that dense smokiness that woody notes often do. This is the sawdust shaving off timber in a warehouse; this is not wood in the forest, it’s almost too picture perfect and there’s none of the resin or sap of nature. Combined with the scent’s medicinal saffron note, this cedar feels like the scent of a very well made particleboard: it’s high end for what it is, shellacked and lacquered, but it is still wood pulp.

SAFFRON

Next is saffron, and here’s where we start to get into the guts of the thing. There are many saffron synthetics used in perfumery - one of the most famous being Safraleine, used magnificently in Tom of Finland (Etat Libre d’Orange, 2007). It is the saffron synthetic that gives Baccarat its trademark medicinal bite, that twist that smells wrong in a way - this is the note that people say smells of bandaids because it conveys a flicker of unease. All great perfumes have an edginess — it’s what keeps them interesting - but most choose to add this though animalic notes or skin-like musks, not by evoking the first aid kit of an officer at the Somme. Medicinal smells turn our stomach both from gut feel - most medicine, after all, is poison - and because of the cultural association of the too-bright hospital, the smell of being unwell, the mis-en-scene of death. Saffron is the great gamble of Baccarat, the love it or hate it note. If an animalic leather or musk is meant to bring edginess to other perfumes by evoking a human body, this note is remarkable for its inhumanity. Saffron can sometimes feel a bit sweaty, fleshy, but there is none of the human here and all too much of the scalpel.

ETHYL MALTOL/VELTOL

And then, of course, the sugar. Ethyl maltol, another molecule that changed perfumery, is poured all over Baccarat like molten sugar syrup. Its use in Baccarat is confronting because sugar does not have a smell, it has a taste, so sugar notes are usually paired with a food scent to lead your nose to the story it wants to tell. Ethyl maltol and patchouli reads as chocolate, ethyl maltol and cherry evokes a lollipop, and on and on through the entire genre of gourmands. BR540 doesn’t make it this simple. It is a profoundly inedible perfume, not interested in being palatable, and yet the overdose of sugar is still there, sweetening the jasmine and the saffron, the tagetes and the ambroxan. Like candied peel, like an embalmment of sugar, a scent to put you off your food for hours and at the same time make you ravenously hungry. There is a syrupy, overindulgent facet to this note in Baccarat. Rather than candy it gives an impression of grenadine, saccharine and ruby-red and thick as oil.

VERAMOSS

This is the most interesting element on the formula sheet. It’s not mentioned in our notes list but is named by Kurkdjian as the ‘synthetic oakmoss’ ingredient. Oakmoss, though you may not believe this, is perhaps the most politically fraught ingredient in perfumery. Natural oakmoss was an indispensable part of the classic perfumer’s palette in the classic fougère and chypre scent structures. Due to controversial decisions by IFRA, the fragrance industry’s regulator (that is funded, coincidentally, by Big Perfume) to restrict the use of oakmoss due to allergen sensitives, this ingredient is now unusable if you want to sell perfume. The race to develop synthetic oakmoss substitutes was on. This is also the note where we have to mention that not all synthetics are equal to one another: just like with natural ingredients, there can be variations in quality of synthetic notes. The higher quality ones are usually ‘captives’, proprietary to one of the Big Perfume houses (and yes, they actually call them that, like they are holding their little synthetic creations prisoner in the scented castle). Perfumers not working for the house that owns a captive have to pay, and pay handsomely, to use them. Veramoss is an IFF captive oakmoss synthetic - the same thing is called Evernyl at Givaudan. It is this note that gives Baccarat its resinous gummy facet, that chewiness that enhances the sweetness of the maltol. Moss notes also act as a fixative, deepening every note and extending their projection. Veramoss may be playing second string here, but Kurkdjian understands that without this note there can be no symphony.

AMBROXAN

Last comes Ambroxan: the villain of the story. This synthetic is a woody, musky scent which is designed to mimic, as the name implies, the famed ambergris. Ambergris, though being one of the few animal derived naturals still considered ethical to use in perfumery (no whales were harmed in the making of this scent), is exorbitantly expensive and hard to source. Even when it can be found, its use in mass market or industrial level perfumery is impossible - too much variation in too little a quantity of product. There are many ambergris imitators, but ambroxan is perhaps the most prevalent. Name a mass market designer scent of the past ten years, especially one designed for men, and the little gremlin will appear: it is the backbone of Aventus (Creed, 2010), the guts of Bleu de Chanel (Chanel, 2010) and Sauvage (Dior, 2015), and the entire skeleton of Molecule 02 (Escentric Molecules, 2008). Its scent, then, is the scent a man in his mid 20’s who oversprayed his cologne that morning as he exits the room: an undeniably synthetic and slightly sweet ambered musky thing, a smell that feels both light and slightly oppressive somehow, like it wants to smother you kindly.

These are the building blocks of Baccarat, but it is not a jasmine perfume or a saffron perfume or an ambroxan perfume. It takes all of these components and diffuses them like a camera lens expanding, wider, wider, until everything is so large and out of focus that you can only see colours bleeding in to one another in a mass of sugared floral saffron musk.

The interplay of these notes create the jeweled world of Baccarat Rouge 540. The sweetness of the ethyl maltol combined with the lemony touch of the tagetes and hedione contrasted against the spice of the saffron evokes a cola scent as our nose struggles to find a reference for what we’re smelling (cola itself being an accord of citrus, cinnamon, vanilla and sugar). The cedarwood and ambroxan form a woody-amber backbone for the scent that is characteristic for perfumery in the 2010s. They are what help to project the scent so strongly - but this is deepened by saffron into becoming something darker and seamier than a typical masculine branded perfume. Indeed the contrast between the saffron, woods, and ambroxan - all pulling towards a more traditionally masculine scent, and the hedione and maltol - more traditionally feminine - are what creates the tension that is able to render this unisex for marketing purposes. All the while, the oakmoss pulls all of these strings together and turns them into more than the sum of their parts. The notes are oversized and overdosed, clashing in to one another, the planets and asteroids that collide to make the space dust that is Baccarat.

Perhaps the most famous element of Baccarat is that this it projects so overwhelmingly. The scent is stomach-churningly loud and its sillage will outlive the sun, but it is not heady or thick or powdery. Instead it has a strangely translucent feel, an airiness due to the lack of complex naturals, that makes the scent feel so modern that it would be inching towards avant-garde if not for the overdose of ethyl maltol.

This is unsurprising considering the amount of synthetics used and that a huge projection was one of Kurkdjian’s goals in the formula. The perfume is huge, like a helium inflated balloon, but it is also endless - it can last days or weeks if sprayed on clothes. People who wear Baccarat almost always end up with a closet full of clothes that smell of Baccarat; it infects; it persists.

Why does this perfume not seem to fade into the background with frequent wear as our noses become accustomed to it? The conclusion I have come to is this: like the sweet poison fruit of some unearthly tree, Baccarat smells like sugar and death. Our sense of smell is designed to detect danger and food, which is why the sweetly poisonous Baccarat can never become a scent your nose acknowledges and then ignores. Your nose smells Baccarat and says eat, and then it says run. It speaks to the animal in you, the ungovernable, the part of you that is Eve grasping the apple, the little tick in your brain that will take what you shouldn’t have exactly because you shouldn’t have it.

This olfactory trick of evoking danger and hunger is why the scent makes people think of wealth and of power. There is a ruthlessness to Baccarat that makes it well suited to CEOs and teenage girls. To me, this smell evokes a panic even as I am drawn to smelling it over and over. The image Baccarat evokes is of the inside of a precious jewel, fractionated and glimmering but also claustrophobic and breathless, as if you are falling endlessly through a jagged, jewelled universe.

Whenever I spray Baccarat Rouge 540, I think about Uncut Gems.

The film, released in 2019 when Baccarat was starting to make the jump from sensation to phenomenon, is about a jewellery store owner who tries desperately to sell off gemstones to pay his gambling debts. The film is a masterclass of anxiety - you start watching it tensed and cannot relax until the credits start to roll, knowing that at some point it’s all going to go wrong, it has to go wrong, but not knowing when or how. The film itself is cast in jewel tones; the soundtrack is unsettling and metallic; the cinematography is shaky and febrile; the momentum sweaty and paranoid.

The entire film feels like a longshot, chaotic and relentless. Uncut Gems is a dark parable, an encapsulated kaleidoscope world on its own that you are sucked in to for the duration of the runtime and simply cannot escape - even if you hit pause, you’re still in there. It is a brilliant film, but a harrowing one. This, to me, is the feeling of Baccarat precisely.

If perfume is an art form, does Baccarat take us that next step forward in our cultural development of perfume? I believe it does. This is a perfume that smells like nothing else on the market. It is not the same limp white floral or blasting fruitchouli accord you have been smelling for 15 years; it is technically a gourmand, which is technically a subset of amber, but the scent is one that defies easy classification precisely because of its newness.

Much like Angel (Thierry Mugler, 1992) created the genre of gourmand, Baccarat will create a new dialect of perfumery, an entire subgenre of its own. I call this style a gourmand bijoux, a sweet-amber scent that’s a step away from realism, a touch more artificial and jewelled. Much like no one could have anticipated Angel sending us down a twenty five year path of olfactory sugared overdose, I don’t know if Baccarat’s bejeweled success will be a good or bad thing for the perfume industry. All I know is that if it brings me more perfumes that unsettle me, that make me think as well as make me feel, than I will be happy indeed.

Imitation

“The success of a scent is not only a matter of how and who creates it, it’s also how you market your idea and how you sell that package.” - Francis Kurkdjian⁷

Open Tiktok and search ‘Baccarat Rouge 540’.

The top results, if your algorithim is similar to mine, are variations on a single constant theme: ‘Is Baccarat Rouge worth the price?’ ‘Is this perfume a true dupe of BR540?’ ‘Top 5 affordable alternatives to Baccarat Rouge’.

A 70ml bottle of Baccarat Rouge 540 will set you back AUD$369. This price is astronomical, and though not uncommon in the niche perfume market, its cost combined with its success and novelty has built a unique culture around Baccarat - a culture of imitation.

Price may not always be a factor in the artistic value of a perfume, but it is always a factor in its success. As a general rule the more mass market a perfume house is scaled, the more speculative their pricing becomes relating to cost of production. If a small, artisanal house cost at $250 for 50ml, it usually because of the quality of ingredients and to cover their own costs of production. For larger houses, and specifically those like Maison Francis Kurkdjian which are owned by conglomerates, pricing is more opaque.

The psychology of price and perfume is a topic on which we could spend days analysing and never run out of things to say. Due to the cloak-and-dagger nature of the industry, the lack of average consumer knowledge of the cost of ingredients, and oligopoly of Big Perfume, there is a disconnect between the cost of production and the cost of sale in perfume that only grows wider with the relentless rise of the niche market.

Why does the consumer accept this? Because to many people there is social value in owning an expensive perfume - even if the value is only performative. There is a trust from the consumer that a niche perfume costs $300 because it is of better quality than a designer perfume that sells for $150. This trust is unfortunately misplaced, as the vast majority of niche perfumes are made by the same perfumers at the same big houses using the same accords as everything on the designer shelf at your local department store.

The knowledge that people will see a Byredo or Le Labo or Maison Francis Kurkdjian perfume bottle on the shelf of your Instagram post and know you spent $350 to get it is the great lure of this new era of perfume. You can’t just smell expensive, you have to be expensive. It is now not only the scent that sells but the bottle, the prestige, and the price itself.

But what if you don’t have $370 to spare and still love Baccarat? Luckily, there is an entire market of lower priced perfumes to meet that need - if you are brave enough to enter the murky world of perfume dupes.

dupe - 1 - /djuːp/ - noun - a duplicate or copy of something.

dupe - 2 - /djuːp/ - verb - to decieve or trick.

“Dupe culture”, in which budget friendly versions of luxury items - “duplicates” - are sold by knock off companies, is a widely observed phenomenon across practically all consumer industries. It has expanded in popularity - and criticism - in recent years due to forming essentially its own genre of content on TikTok. Dupe culture has much overlap with fast fashion and is prone to the same criticisms, with companies like Shein, Alibaba, Zara, and H&M all selling dupes of luxury consumer goods.

Perfume as an industry is highly susceptible to dupe culture due to the lack of consumer information and secrecy that surrounds it, coupled with a troubling lack of intellectual copyright law for formulas. This culture has lead to what we may call an industry policy of soft plagiarisation for decades: a perfume house releases a new bestseller, other perfumers will get a bottle, run it through the chromatograph, get a rough idea on how the sausage is made, and release a version of their own to meet consumer demands. Many of the great perfumes have been made this way: Opium (YSL, 1977) begets Coco (Chanel, 1984) begets Posion (Dior, 1985), and so on until demand runs dry.

But as the niche market gets bigger, the price goes up, and there are whole corners of the market which may be copying one another but remain out of the price range of the average consumer. The buyer wants a perfume that smells like niche, but doesn’t want to pay niche prices, and doesn’t think they can get what they want at the designer counter. What do we do?

Send in the clones.

It is important to note that clone - or imitation - houses are not a new concept. The budget clone house has existed in tourist destinations across the world for decades, often with set ups like this that offer ‘our tribute to (insert famous perfume here)’ on tap in delightfully oversized apothecary jars. The legally grey area that the perfume industry willingly keeps itself in leads to the creation of these clones. In the past ten years clone houses have exploded in number and reach though the growing interest in niche perfume - especially men’s perfume, lead by the cult-like obsession with modern perfumery’s casus belli Aventus. People are buying, clones are selling, social media is hawking, and budget dupe houses have now reached closer to the mainstream than they ever have before.

Clone houses are one of the most widely debated corners of the perfume world. Are they legal? Are they ethical? Is it plagiarism? Is it disrespectful to the perfumer to buy such a blatant copy? Are clone houses really that different than the soft copying that legitimate perfume houses have been doing for decades? Would clone houses even exist if niche houses hadn’t raised the median price of perfume so exorbitantly? Are clone houses democratising perfume or destroying it?

The politics of cloning surround online fragrance communities like a fug of…. well, like a fug of Baccarat Rouge 540. There are no easy answers, only endless circling sillage.

Perfume formulas are not copyrighted and not published, but are easily recreated with the use of a gas chromatograph. Kurkdjian himself has stated that the formula for Baccarat is simple and almost entirely synthetic. This means that Baccarat Rouge 540 may just be the most dupeable perfume on the planet.

The art of selling a perfume clone is a delicate tightrope to walk. Much like Aldi branded goods, the cloned perfume must skirt as close as possible to the original name whilst remaining on the right side of trademark infringement. This leads to perfumes with names such as Red Baccara, Baroque, Ethereal Saffron, Love in Baccarat, and Bliss Release. Some dupe houses don’t have time for euphemisms and will simply say ‘our impression of Baccarat Rouge 540’ - they know what they’re selling and assume you know what you’re buying, and are gambling that the low low price will mitigate any discomfort you may feel. You want to smell like Baccarat. Clone houses can fix that.

There are more clones of Baccarat Rouge than it would be practicable to list, both from dupe houses and mainstream companies. The most famous of them is Cloud (Ariana Grande, 2018). The sensation of Baccarat is inextricably tied to the success of Cloud - I have written about Cloud previously here. Where Baccarat did not have traditional advertising or the in-store presence of a designer scent, it has Cloud and Red Temptation (Zara, 2020) and Brazilian Crush Cheirosa '68 (Sol de Janeiro, 2022), all affordable duplicates that have been their own word of mouth successes, which then lead back to Baccarat upon a simple web search. Then, once the spell of Baccarat is cast but the price remains too high, people turn to the deep clone houses.

It’s impossible to know how many units of perfumes pretending to be Baccarat have been sold. Considering the price of the original compared to the fact that it is difficult to walk from one end of a shopping mall to the other without smelling the Baccarat DNA at least twice, Baccarat might be the first perfume that has conquered the world by imitation.

Why does Baccarat Rouge cost AUD$369 for 70ml? We know that there are no high cost ingredients in the formula. The only answer is that Baccarat costs that much because Francis Kurkdjian and Marc Chaya want it to cost that much, and they are able to price it as such because they know it will sell. For many who are new to niche this sticker price is a shock, but it is unfortunately quite standard in the industry.

Because perfume pricing, like investment banking, is speculative, people get defensive about their luxury perfumes. There are just as many people online saying that nothing can compare to the original Baccarat as there are saying that a $20 clone gives the exact same effect. The buyer of the original bottle needs to believe there is something unique about the original; the buyer of clone must believe that the clone is as good as the original. Both cannot be true.

Putting aside the emotion of the argument, let us compare formulas themselves. In @fragrance.drama’s chromatograph analysis, there is a comparison between Baccarat Rouge 540 and Cloud:

The verdict is in. It's almost entirely the same perfume.

The nose usually doesn’t lie - many Baccarat fanatics acknowledge that some of its many, many dupes do smell similar to their beloved bottle, but to them it doesn’t matter. Baccarat lasts longer, in their opinion; it smells richer; it has more complexity and depth. And maybe it does. Or maybe it’s hard to acknowledge that more of your $370 was spent on the name on the bottle than its contents.

This, in its essence, is the paradox of niche. The scents are not designed to finely crafted or subtle; they are not quiet luxury. A niche perfume is shouting at the top of its lungs from first spray to drydown; it advertises itself with every spray and that is what people are paying for. They’re paying to be noticed - on their instagram feeds or at the grocery store, there is value to the consumer in people knowing you have bought an expensive perfume.

Niche perfume is loud luxury and its buyers are paying. They are paying for a perfume that will project from your wrists and your throat and your hair in a nuclear mushroom cloud of ambroxan and hedione and sex and death, all so the uninitiated will walk up to you with stars in their eyes and ask what you are wearing. And then you can lean over like you are a queen granting a boon, like you are sharing a delicious secret, and whisper:

‘It’s Baccarat Rouge 540…’

Phenomenon

The moment the corridors of high schools began to smell like Baccarat is when it truly became a part of mainstream culture, and that is when it began to die.

Baccarat did what Marc Chaya and Kurkdjian wanted it to: catapulted them and their brand into perfume superstardom. After its initial limited run, Baccarat was released into the wider Maison Francis Kurkdjian portfolio in 2015. By 2017, MFK had realised the niche dream and was bought out by LVMH. In 2021, LVMH announced that as well as maintaining his own brand, Kurkdjian would become in-house perfumer at Dior.

If we all have one truly great idea in our lives, Baccarat is Kurkdjian’s. Perfume fanatics will argue this - Grand Soir (Maison Francis Kurkdjian, 2016), Narciso Rodriguez for Her, Le Male, and Eau Noire are all bandied as contenders for Kurkdjian’s best perfume, and there’s an argument to be made for each, but all of them are variations on the great themes of traditional French perfumery - none of them are novel.

Perhaps Kurkdjian knew that he had lightning in a bottle with Baccarat; perhaps he only hoped. Besides the fame and the money, the dream job and the stores with your name in every high end mall in the world, it must be some kind of feeling to walk down the street and smell that smell, the one you spent twenty years perfecting, wafting past you. I wonder if he can tell when what he’s smelling is a dupe; or if, like the rest of us, he is none the wiser.

No one can accuse Kurkdjian of not capitalising on his lightning. Baccarat Rouge 540 has spawned an extrait, a hair mist, a body lotion, a body gel, a soap and a candle, and it success has generated increased interest in the rest of the Maison Francis Kurkdjian line. Kurkdjian is relatively young for a perfumer, and could continue to create for decades to come. He will probably never capture that lightning again - but to do it even once was all the luck he needed.

Baccarat has become so ubiquitous that it is doomed to fall. Even now the tide is turning and people speak of being tired of its unique scent profile. Once everyone starts wearing a perfume, no one wants to wear that perfume. The one common denominator of nearly every #perfumetok pundit, YouTube reviewer, and once a year perfume shopper is that they want to smell unique, and you can’t do that wearing the same bottle everyone else has got - even when that bottle costs $350. The jig is up; you no longer smell mysterious or alluring; you smell, like the rest of us, of sugar and death. You smell, like the rest of us, of Baccarat Rouge.

Since the last pandemic lockdown lifted in 2022, I have known that if I leave my house and go somewhere that contains more than fifty people I am going to smell the DNA of Baccarat Rouge 540. Watching Baccarat grow from a perfume we would rave about in online perfume circles to its conquest of beauty site editors and instagram gurus to total mainstream domination is like watching olfactory history being written in real time. This is how a perfume becomes a phenomenon; this is how perfumes become synonymous with the era they become famous in; this is how scent becomes legacy.

The way Baccarat will become connected to this moment in time is through action and then memory. You will go out to the store or to the club or to the cafe and smell that unique saffron-ambroxan sillage on yourself or someone around you, and this will happen hundreds of times and then suddenly not at all, and then in five years or ten you will smell it again and be thrown back to here and now. It is this, the creation of a cultural olfactive memory, that will make Baccarat a legend.

There are people who will hold fast and keep spraying long after the zeitgeist has passed. There are still people, after all, who wear Angel; who wear Poison; who wear Opium and Mitsouko, who never stopped spraying since that first spritz however many years ago. Because the perfume spoke to them - because it had become a part of them - because spraying it became a memory that evoked memories.

This is what Baccarat will become for you. Whatever the past year of your life has been, in ten years or in twenty you’ll catch that medicinal sugar melody and be thrown back to right now, the scented backdrop of the early 2020’s. This will happen even if you don’t wear Baccarat - maybe especially if you don’t wear it, for then it is the smell you smelled everywhere but not on you, not a personal olfactory memory but a cultural one. It will be the smell of your first job or your first car; the smell of coming out of lockdown; the smell of finding out who you are and then forgetting again; the smell that lingered on your clothes after embracing someone you loved.

I think people wear Baccarat Rouge 540 because they like it, and they like it because they’ve never smelled anything like it before, or because it’s so expensive that it must smell like wealth, or because it makes them feel something. And when it’s not new anymore and the way it makes you feel shifts then you will stop wearing Baccarat or Cloud or Instant Crush or Red Temptation.

But the bottle will still sit there, and in ten years or twenty you will spray it and remember where you were when you wore it; you may even remember the first time you ever smelled it. They still live in that moment, that other you, the you you were, the person who sprayed that perfume and made it a memory.

You can visit that person whenever you like. They will live, forever bejewelled, in the red-gold bottle of Baccarat. ◙

Sources

All prices are current to the Australian dollar as at January 22, 2024.

¹ Sources vary on whether Kurkdjian was 24, 25, or 26 when he created Le Male. I have used the official MFK website, which states he was 24.

² “Our Story”, Maison Francis Kurkdjian

³ Baccarat Rouge 540: the story behind the cult perfume with its creator, Francis Kurkdjian, Wallpaper

⁴ ‘Baccarat Rouge 540’, Maison Francis Kurkdjian

⁵ ‘Baccarat Rouge 540’, Fragrantica

⁶ How Maison Francis Kurkdjian Created the Iconic Baccarat Rouge 540, Our Favorite French Perfume, Vogue

⁷ “Seventeen Families” – An Exclusive Interview With Francis Kurkdjian, Persolaise

Further Reading

The Story Behind Baccarat Rouge 540, The Most Popular Perfume Everywhere RN

History of the Hero: Maison Francis Kurkdjian Baccarat Rouge 540

Maison Francis Kurkdjian: A Superstar Perfumer’s Entrepreneurial Journey

Message in a bottle – Glass interviews leading perfumer Francis Kurkdjian

If you are interested in more of my writing on perfume, here is my deep dive on niche house Le Labo and here is my Cultural Autopsy of the Celebrity Perfume. I write other articles such as this one on this Substack, and can be found talking about perfume on twitter and Instagram.

Post Script

I have been intending to write an article about Baccarat Rouge 540 for some time now, but life got in the way - it has a tendency to do that. It may be that there is no desire for anyone to read nearly eight thousand words about this perfume, but my goal has always been to write the kind of perfume analysis I have always craved to find in my many years pursuing this hobby, and it’s not in my nature to shallow dive. All errors are my own; the opinions I stand by. I hope you found some value or entertainment from this article; it’s been a long time coming.

It will likely not shock you, but I listened almost exclusively to the Uncut Gems soundtrack when writing this piece. Give it a listen and do watch the film - but do it on a day you can embrace some stress in your life.

Follow @fragrance.drama on instragram if you haven’t. The movement towards transparency in the fragrance industry is a vital one.

P.S. I changed the name of the newsletter; there was no other reason except I felt like it.

If you read this far, thank you.

I had a desire to read nearly eight thousand words about this perfume. Thank you

This was an insanely good article! I love the aroma chemical explanations. Glad to see you back, the le labo article is a favorite.