A Question of Soul: Perfumery at Le Labo

An in-depth analysis of the perfumes and culture of Le Labo.

This is the first in the House Overview series, which explores individual perfume houses in depth.

On a crowded grey street in New York City there is a small store fitted out in black and white. The floor is natural wood and the beams are exposed; the light is stark and the fixtures are cold metal. This store doesn’t care if you come in or not; it is industrial-chic, the mad scientist meets the mean barista. There are stores just like it in Hong Kong and in Tokyo, in Dubai and Copenhagen, in Amsterdam and Moscow and Cape Town, and from their doors waft the scents of black tea and palo santo, violet leaf and bergamot.

This little store is called Le Labo.

You might be fooled by the brand name into thinking this is a French house, but Le Labo was created in New York in 2006 by founders Edouard Roschi and Fabrice Penot. After an initial launch of 10 perfumes and one candle, Le Labo now includes 32 scents and an entire supporting army of scented products. In the scant fifteen years since its launch it has grown to become a niche perfume empire.

The brand thesis of Le Labo states:

We believe that there are too many bottles of perfume and not enough soulful fragrances. We believe the soul of a fragrance comes from the intention with which it is created and the attention with which it is prepared. We believe fine perfumery must create a shock - the shock of the new, combined with the shock of the intimately familiar… We believe in the soulful power of thoughtful hands: hand-picked roses, hand-poured candles, hand-formulated perfumes and handshake agreements. We believe in slow perfume. We believe New York made us this way, with a dose of Wabi-Sabi and a few lines from Thoreau.

If you have even a passing interest in perfume, you are familiar this brand: the infuriating perfume names, the minimalist labels, the achingly Brooklyn-in-2013 hipster aesthetic. If you have no interest in perfume but live in a city or town populated by other people, you have probably smelled Le Labo in the guise of its most obvious child: the blockbuster fragrance that is Santal 33.

Le Labo are one of the giants of niche perfume, a brand popular with fragrance aficionados and laymen alike. They are the vanguard of rising prices in perfumery: a 100ml bottle of Le Labo will cost you $425. How did Le Labo become so popular? What does the brand have to say about perfumery, and do their scents represent the artistry and innovation expected for their asking price? When reviewing Le Labo’s scents for Perfumes: the Guide, Luca Turin writes of his interactions with the brand:

“From their gorgeous website to their Soviet sanatorium-style New York shop, Le Labo is so hip it hurts. They initially refused to send us samples, one of only two firms to do so. The reasons given? “We don’t believe in critics in perfumery” and “We believe that writing about perfume is like dancing about architecture.” Helpfully, though, they were also of the opinion that “if there were some more good evaluators in the press, some brands would be more afraid to launch new crap.” ¹

In this overview we will dance about some architecture and explore the wabi-sabi world of Le Labo.

PART ONE - ‘Niche is the New Black’

The genesis of Le Labo lies in the rise of niche perfumery twenty years ago.

The state of the fragrance industry in 2006, when Le Labo launched its first ten perfumes, was less stratified than it is now. Designer brands like Chanel and Dior still reigned supreme, exclusive lines were rare, celebrity perfume was rampant and niche was a small corner of the market - but slowly getting bigger.

A niche perfume house is a brand which only sells perfume and derivative products (candles, room sprays, etc), and whose owners do not create their own scents. The niche house hires perfumers, either from the large fragrance firms such as Givaudan and Firmenich or freelancers, to create their perfumes. Thus the owner of a niche brand is the creative director who works with the perfumer on the product. As Le Labo’s co-owner Fabrice Penot explains:

“Perfumers may know how to develop perfume but that doesn’t mean they know how to create one that will be a success. They need a vision or a creative director to help them translate that into the right recipe. It’s like an artist – you may be talented but you still need an agent and gallery. That’s our job.”

The first niche brand whose DNA can be clearly seen stamped on Le Labo is perhaps unexpected: the house of Jo Malone. The bombast that was perfumery in the 1980’s gave birth to trend of minimalism in the 90’s, and in this regard London based beautician Jo Malone lead the charge. Her creations were simple and linear colognes, perfume for people who didn’t like perfume, and most importantly they were exactly what they said they were on the bottle.

High end perfumes were not named after the things that they smelled of - with exceptions like Vetiver (Guerlain, 1959) - until Malone released her first scent called Nutmeg & Ginger (Jo Malone, 1991). The perfume smells like nothing more than fresh nutmeg and a zing of ginger for about two hours and then it is gone. There was something so clean about it, so minimalist, so fresh and daring: Poison and Opium were out and simplicity was in. People liked buying scents that smelled how they said they would smell on the bottle.

Malone went on to release Grapefruit (1992), Vetyver (1996), and her pièce de résistance Lime Basil and Mandarin (1999). Jo Malone was one of the juggernauts of late 90’s perfumery, and was bought out by beauty conglomerate Estée Lauder in 1999.

The other house that preceded Le Labo was Editions de Parfums Frédéric Malle. This was a niche company launched in 2000 with a singular mission: to treat perfumery as art. Taking its inspiration from niche forefathers such as Serge Lutens and L'Artisan Parfumeur, Frédéric Malle commissioned the best of the best, perfumers from Givaudan and Firmenich and Symrise, to make their dream scents. Formula budget was not obstacle and bottle price reflected it: the first Editions de Parfums released in 2000 included iconic scents Musc Ravageur, Lipstick Rose and En Passant and were all priced at over $200 for 50ml. Frédéric Malle proved that people were willing to pay big money for artisanal niche perfumery. Editions de Parfums was a phenomenal success… and was sold to Estée Lauder in 2014.

Co-founder of Le Labo, Fabrice Penot, says that the company has “no model, but lots of respect for Frédéric Malle. We share with him a vision of perfumery.”

The third company whose influence on Le Labo is perhaps largest of all is the Australian skincare brand Aesop. The brand was founded in 1987 and long before it was fashionable, Aesop were selling high priced smelly things in bottles that looked like they fell off a truck on the way from the laboratory.

Le Labo’s minimalist aesthetic and pharmaceutical style stores are eerily similar to Aesop, with one crucial difference: Aesop is meant to evoke a fancy spa and Le Labo is meant to evoke a fancy spa in Silent Hill. Aesop’s product packaging is also similar to Le Labo’s. They are characterised by no frills black-and-white labels on plain bottles. An amber bottle of Aesop handwash on the sink is a status symbol, a freemason’s compass indicating to those in the know that the person who posted it is a member of the tribe. The monochrome Aesop pump and the minimalist Le Labo spray are brothers in arms, often featuring together in the shelfie, an Instagram trend where people post pictures of their product shelves.

Beyond the stylistically similar packaging and the conceptually similar stores, Aesop’s brand approach would inspire Le Labo in another crucial way: Aesop does not spend any money on advertising. They also do not have discounts or sales - certainly nothing for Black Friday. This is an ethos Le Labo would make their own.

While no advertising might not seem to be good for business, it is good for the right kind of business. When your products are priced at the luxury end like Aesop and Le Labo the type of consumer you are courting is one who wants to feel special, luxe, exclusive. Having to find the brand - by seeking them out, by word-of-mouth, by spying a product in an Instagram post - makes the consumer feel like they are in on a secret. This helps increase customer loyalty and earns a brand the lauded label of ‘cult’. For a niche brand, this is the Golden Fleece: you want to sell a cult beauty product. You want to sell a cult perfume.

Onto the scene enter Edouard Roschi and Fabrice Penot.

These were not were not two men who came from nothing: both were fragrance industry insiders. They had both worked for the big fragrance oil houses (Roschi at Firmenich, Penot at Symrise), the companies who supply natural materials and hire perfumers who compete for briefs to create perfumes. They met when managing perfumery at Armani under the oversight of L’Oreal. Roschi describes his work at Armani as wide reaching:

“(Penot) was in charge of developing its niche brands and managing one of the largest franchises, Acqua di Gio, and I was in charge of the Emporio Armani brand. We were developing entire concepts. It starts from identifying the story that you want to share with the clients, to briefing design agencies for the bottle, perfumers for the perfume, imagining how that story can be told to journalists [and] setting it up in points of sale and distribution channels. It starts from nothing; from ‘What can I do for this year’s launch?’ to the production and selling of a bottle that translates that initial vision.”

Feeling stifled by the lack of creative freedom at Armani, they struck out on their own to begin Le Labo in 2006. Penot and Roschi relied on industry connections and loans from friends to establish the brand. Lacking the money to hire architects, they fitted out the first Le Labo store in New York themselves.

Perfumery is not an easy business to become established in. The market is saturated, competition is fierce, and for niche brands word-of-mouth is crucial for success. In 2006, before the explosion of social media, the choice to have no marketing budget was a risk. But Roschi and Penot had been to the highest echelons of the industry. They knew that with networking they could get the right perfumers (from their former companies of Symrise and Firmenich), the right location (a store in Nolita, a trendy Manhattan neighbourhood) and the right press coverage (an exclusive article covering their opening in W magazine) to make the brand a hit.

Roschi and Penot knew that they were creating a brand to fill a void in the perfume market. Penot puts it simply:

"It was just a business model with your own point of sale with an expensive price and an environment and aesthetic that wasn't meeting all the landmarks of the usual perfume business model. It was not reasonable for anyone. And that's why it makes sense."

And so the dream of Le Labo came to be: a house of expensive scents like Frédéric Malle, named after their main ingredients like Jo Malone, styled and sold in stores modeled like Aesop. The hybrid hipster-niche house had been born.

Niche houses were carving out a new category in perfumery: expensive perfumes for discerning buyers. Founder of Le Labo, Fabrice Penot, points out:

“Niche is the new black in perfumery, very good for us. But if designer brands had respected their clients giving them beautiful perfume and not soups for years, the former would not fly away to us.”

PART TWO: A Rose By Any Other Name

Every brand has got to have a hook, a bit, an aesthetic - what makes Le Labo stand out from the pack? The clue is in the name. Le Labo, which simply means the lab in French, styles itself as a pseudo-scientific perfume ‘laboratory’. It eschews anything hedonistic or ‘poetic’ - the usual stomping ground of perfume - for a cultivated minimalism.

Le Labo’s hook is the idea of stripping perfumery down to its fundamentals. As a gimmick it’s clever - raw materials are highlighted and each perfume’s web page has an Instagram worthy ‘deconstruction’ of the naturals used within the note pyramid. Though the “laboratory” where Le Labo perfumes are created is the same as every other niche house - that is to say, the laboratories at Givaudan and Firmenich - Le Labo is selling the idea of the savant scientist, the man at the perfume organ pondering life and the world and turning it into perfume. Roschi recalls the concept of Le Labo being formed:

“People were trying to get attention through funky packaging and crazy adverts, but they were forgetting what was extremely sexy and still is today is the perfumer’s work — the craftsmanship that’s behind the work, and his or her expertise — the ingredients, their origin, the people that pick them, how they picked them how they transformed their vision into a perfume. The whole scenery of a perfumer’s lab is very evocative by itself.”

Le Labo perfumes are sold in bottles that look like Florence flasks and are labeled like crime scene evidence. But mostly importantly of all, Le Labo perfumes are not given evocative, mass-market appealing names. They are baptised with methodical consistency: each perfume is named after the major ingredient in the formula, followed by the number of ingredients in the formula.

Here is the flaw in Le Labo’s grand plan: the major ingredient in a perfume is rarely ever what the perfume smells like. Perfume is a cloak-and-dagger business - some ingredients are put into perfumes not for their scent but because they amplify all the other notes. These are called fixatives and they can be natural like vetiver or synthetic like Timbersilk. A perfume can have an overdose of a fixative and not smell of it whatsoever; it can have a tiny drop of rose essence and smell like you’ve drowned in Turkish Delight. The amount of an ingredient in a perfume has almost no correlation to the final scent. If you bake a cake with seventeen products and flour is the major ingredient you would still call it a cake, not Flour 17.

Thus Le Labo have created a portfolio of perfumes named after natural ingredients that mostly do not smell like those ingredients. They are the bizarro Jo Malone. This may be funny if their perfumes were called Nutmeg & Ginger and smelled of tomato leaf, but becomes infuriating when the average sniffer probably does not know what labdanum smells like and after visiting a Le Labo store will believe it is the talcum powder and civet stink of Labdanum 18. The numbering system is confusing as well - do they stand for individual notes or accords? Would amber - traditionally a combination of vanilla, labdanum, and benzoin - count as one or three in the final tally?

Co-owner Fabrice Penot commented on the issue in an interview:

“We did not name our creations this way to tell you how they were going to smell, we called them this way to be as close to the formula as possible, to be away from a poetic bias that would impact you mentally before you close your eyes and smell the perfume itself. I guess the bias still exist in the solution we favored, apparently, which is too bad … it is pretty disappointing to see critics who have a public voice getting stuck in this rhetoric of, "Hey! Rose 31 does not smell like rose so I don't like it" and witness them not being able to be just moved by the smell itself. I am not saying Rose 31 should move everyone, I am saying if you are a serious critic, there should be a better argument for or against this perfume than the relevancy of its name.”

What is the connection between a perfume and its name? Is it all, as Penot claims, poetics? Would the classics be as classic if they didn’t have those names that ring in your mind and seem to fit so perfectly with the scent, Mitsouko and Joy and Opium, Cool Water and Carnal Flower?

Is the Le Labo perfume meant for a scent literate person who knows that Labdanum 18 does not smell of labdanum, in an attempt to spark conversation about perfume composition? Or is it meant for the scent casual person who is going to smell every sandalwood perfume after Santal 33 and wonder if their nose is broken? Are we meant to smell Le Labo perfumes in the same way the adjudicators of the Art and Olfaction awards judge the entries: blind, with no information on what they are called or what they are intending to evoke?

And as for poetics… In describing the perfumes he wishes to create, Roschi confessed:

“Have you read the novel Perfume by Patrick Suskind? His book is about a psychopath that kills beautiful women and peels the skin off their bodies. He then distils it down to create this scent that makes people go crazy and start eating each other. I love the idea of a fragrance that is extremely sensorial. It’s like the smell of the person you love – it drives you crazy."

The language of the ingredients in Le Labo’s perfume titles vary, presumably based on what sounds most trendy to the brand. Vetiver is simply vetiver but oakmoss is mousse de chene; rose is rose but tobacco is tabac. Le Labo may not be cultivating the traditional poetics of perfumery, but they are certainly trying to craft their own style and aesthetic with their bizarre naming system. There may be a bias when you go to spray a Le Labo perfume, but perhaps the consumer can be forgiven for assuming a perfume called Rose will smell like a rose.

Interestingly, nearly all of Le Labo’s perfumes are named after natural ingredients, not synthetics. Given the overdose of ambroxan evident in many of their scents - Penot has stated many times that this synthetic is the most used ingredient in Le Labo perfumes - and the high restrictions placed on natural ingredients by regulatory bodies such as IFRA, I am skeptical that every Le Labo perfume is natural dominated.

Language is loose and secrecy is rife when it comes to perfumery; many brands will claim their perfume includes a natural when it really has the synthetic counterpart, Polysantol in lieu of sandalwood. But the emphasis Le Labo places on natural ingredients in their perfumes places a greater scrutiny on their claims.

There are 18 scents in Le Labo’s Classic Collection. What do these strangely named, “sensorial” creatures smell like?

PART THREE: The Specimens

I first encountered Le Labo before their 2014 buyout by Estée Lauder, when they were still an independent brand. I took advantage of their sampling service because it was well priced and when it comes to perfume I am always curious. It is easier to find Le Labo now - they have concession stands in beauty stores as well as their own flagships. I have tried every Le Labo scent on paper and on my skin.

Lys 41 is a fresh and scrubby white floral, with a touch of buttery tuberose that gives the overall effect of a fancy bar of soap. It is a combination of tuberose, jasmine, and lily that uses a creamy musk to keep the florals from being too sharp and abrasive. This is a perfume that feels as if it is trying to reinvent the white floral, as Carnal Flower (Frédéric Malle, 2003) did. But Lys 41 lacks Carnal Flower’s medicinal eucalyptus top note and also its unapologetic loudness, the way its perfumer Dominique Ropion was not afraid to let huge notes slam together and create something beautiful between them. Lys 41 hums along, too pleasant to be a bad perfume and too characterless to be a good one.

Baie 19 puts its cards on the table as soon as I spray it - this perfume is attempting to recreate petrichor, the smell of wet earth after rain. This one of nature’s loveliest smells, and if it’s done well in perfume it can be quite evocative. The basic structure of a petrichor perfume is an aquatic note and a woody note - the rain and the earth respectively - and Baie 19 attempts to do this with patchouli and calone, a synthetic made popular in the 1990’s through such watery behemoths as L’eau d’Issey (Issey Miyake, 1994). Calone is a huge scent that smells of a briny beach and also of fresh melon; it is almost always unbearable to my nose. Baie 19 combines the unpleasantly balmy note of calone with the mulchy scent of patchouli leaves that have become waterlogged and putrid. The only good thing about Baie 19 is that it has no longevity and you need not suffer its presence for longer than an hour. A press release from Le Labo says,"Truth is… Baie 19 should have been called Water 19.” Water would have smelled better than this.

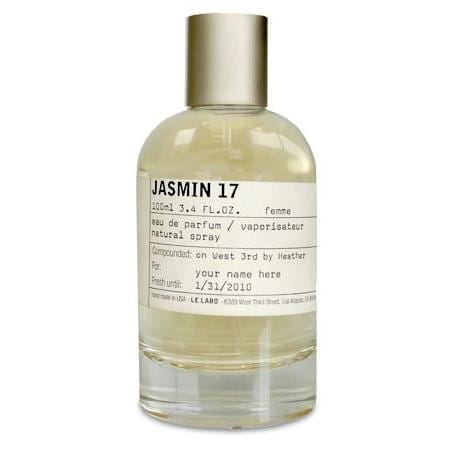

Jasmin 17 is, to my deep shock, an interesting white floral. Jasmine in perfume has many different facets: there is the fresh and green floral jasmine; the synthetic humming jasmine (also known as hedione); the indolic and carnal jasmine; and the overwrought jasmine that always smells like toilet air freshener. Usually these notes can be seen on their own and not together: Jasmin 17 remedies this by putting every jasmine in perfumery on display, all at once. The mix isn’t unpleasant on the blotter but it becomes sickly sweet on skin. Jasmin 17 feels more like a failed science experiment than a perfume.

Vetiver 46 is where Le Labo starts to get interesting. Vetiver is also a note that has a tipping point - it is a wonderful and indiscernible fixative, as in Habanita (Molinard, 1921), but reach the point of too much vetiver and it will be all you smell, as in Vetiver (Guerlain, 1959), Fat Electrician: Semi Modern Vetiver (Etat Libre d’Orange, 2011), and Vetiver Extraordinare (Frédéric Malle, 2003). But as I sprayed Vetiver 46 on the blotter there was no vetiver to be found. The scent redeemed itself by still smelling quite good: upon first blast it has a fatty, almost buttery quality, backed by a smoky and slightly sweet incense. This sounds strange but when these accords combine they give one of the loveliest smells in the world: the scent of a candle that has just been snuffed. Vetiver can pull in this direction when blended well with incense notes, such as in the gorgeous Grey Vetiver (Tom Ford, 2011). Vetiver 46 is not a contemplative smell like a straightfoward incense perfume; it is dirtier, earthier, more sensual and intimate. But Vetiver 46’s fatal flaw is that it is almost identical to another perfume I love, Comme des Garcons Man 2 (Comme des Garcons, 2006). Created by perfumer Mark Buxton, CDG2 Man uses odd numbered aldehydes to give the smoky, slightly sweet scent of just-snuffed candles. Curious as to whether Vetiver 46 was simply a dupe of CDG2 Man, I looked it up… to find that the perfumer of Vetiver 46 is none other than Mark Buxton. The perfumes are, essentially, the same - except that Vetiver 46 will cost you $425 for 100ml, and Comme des Garcons Man 2 will cost you $171.

Fleur d’Orangeur 27 and Neroli 36 are utter failures. They are both fleeting perfumes done in the traditional cologne style, highlighting notes of the bigarada tree. Without the bitter orange tree, perfumery would probably not exist as we know it. It is incredibly fragrant: its leaves are steam distilled into neroli and extracted from solvent into orange blossom, and its branches and twigs are crushed and distilled into a note known as petitgrain. All three notes are related but distinct: neroli is a more citrusy and waxy; orange blossom is sweeter and more floral; petitgrain is woodier and more herbal. All three are top notes in perfumery, being the most unstable molecules in a formula - they flare and fade quickest. Cologne scents, which are dominated by citruses like neroli, are never going to last more than an hour or two. The recent surge in high end scents that follow the cologne structure, such as Neroli Portofino (Tom Ford, 2006), is laughable. A cologne should come in a huge bottle, be dirt cheap, and be splashed on as often and in as large a quantity as you desire. There is nothing wrong with Fleur d’Orangeur 27 and Neroli 36 - they are simple, clean, and linear reconstructions of orange blossom and neroli. But you will get the same quality and longevity found in them from a bottle of orange blossom water sold at your local Middle Eastern grocery store, for about $415 less.

AnOther 13 is the one exception to Le Labo’s naming rule. It is an entry into the current trend of nothing perfumes, minimalist scents that are meant to ‘effortlessly blend’ with your body chemistry and smell like ‘you, but better’. These perfumes are almost all musk, cedar, or musk-and-cedar synthetic creations. Their inspiration comes from the success of Escentric 01 (Escentric Molecules, 2006) but their genesis traces further back to the clean perfume trend that began in the 1990’s with CKOne (Calvin Klein, 1991). AnOther 13 is very typical of its species, which means in perfume terms that it is bad. It is wan and halfhearted musk, overloaded with synthetics that you will either not be able to smell or that will give you a headache. This is rounded out by a sepia-toned pear note that hounds you with its sickly stewed fruit pallor every step of the way. A collaboration with AnOther magazine, this is a perfume created by the incredibly talented Nathalie Lorson of Firmenich, who created Encre Noire (Lalique, 2006), Bentley for Men Intense (Bentley, 2011), and Black Opium (YSL, 2016). Also for Le Labo she created city exclusives Cuir 28 Dubai and Poivre 23 London.

Ambrette 9 is an exercise in frustration. Ambrette, also known as musk mallow, is a plant that serves as a natural alternative to traditional deer musk. It smells deeper, stronger, and slightly more medicinal than the common white musks used in perfumery (and in your laundry powder). But Ambrette 9 does not smell of ambrette - it smells of foam banana candies that have been left too long in a hot place and are starting to stew in their own sugar. This unhappy smell of a ruined childhood is enhanced by a creamy musk. Ambrette 9 is a musk scent with the edges polished off until it is a pitiful thing that sits on your skin for a moment, looks around awkwardly, and then disappears into the ether.

Labdanum 18 is where I take a step back and breathe for a moment. I know I am getting too caught up in the naming of it all. Take the perfume in by itself alone. I close my eyes and choose the next sample at random, fumbling to spray it on the blotter. When I eventually do, I smell... a boudoir in Weimar Germany. It's the first image my mind jumps to and it sticks - this is powdery. Like seriously powdery. This perfume is a powder bomb hued in dark tones, with the unsettling smell of dirty skin in the base. It smells strangely violent - more Peaky Blinders than Downton Abbey. Reinforcing the powder is a strong civet, which is a note I struggle with - in small amounts it adds funk and depth to perfume and in large doses it smells like a dirty nappy. This is a large dose of civet. The powder is like talcum but not as clean. The overall effect of the scent is of dirty baby powder. I open my eyes and read the label. Labdanum 18. This is a perfume created by Maurice Roucel of Symrise - a bastion of the industry and of Iris Silver Mist (Serge Lutens, 1992) and Musc Ravageur (Frédéric Malle, 2000) fame. You can see the bones of Musc Ravageur in this Labdanum 18, simmering beneath the walloping dose of civet, but that is a far better perfume than this.

Ylang 49 is a deafening aldehydic floral in the storied 1970’s style of Rive Gauche (YSL, 1971) and Aromatics Elixir (Clinique, 1975). Ylang 49 smells simultaneously like powdery soap, the stem of a green flower, and the mothball flecked overcoat of your least loved and most overbearing aunt. This perfume has personality, for which I give it credit, it’s just that I don’t enjoy it at all. It is finely made but completely derivative, and I do not know why anyone would buy it when Rive Gauche can still be found, singing this same song at $75 a bottle.

Iris 39 came to play ball; it is a vegetal iris in the style of Iris Silver Mist (Serge Lutens, 1995) and Iris Cendre (Naomi Goodsir, 2016). The perfumer of Iris 39 is Frank Voelkl, whom we shall meet again later, and his thesis of embracing the harsher and less-loved qualities of natural ingredients shines through here. This is a comprehensive iris, like the flower itself encased in resin; there is no trace of lipstick or powder as can often be found in iris perfumes. There is a green note, just shy of sharp, that brings to mind the actual iris flower, a living thing - which is clever work considering it is retroactively adding scents from above ground to orris root, the method of cultivation for iris in perfume. The drydown is strange again, an accord I can only describe as fizzy - it smells like diet creaming soda, not too sweet and a little dry but still effervescent. If someone made dry ale but used orris butter instead of ginger, it would smell like Iris 39. A clever and confronting perfume.

Tonka 25 is a nothing perfume, similar to AnOther 13. It begins with some abstract spices - you know it smells spicy, you just can’t put a name to the specific notes. This fades quickly and you are left with cedar and musk, limping along for an hour until the whole thing vanishes. I get almost no tonka, which isn’t surprising - the main component of the tonka bean, coumarin, was the first synthetic molecule ever used in perfumery and it has been fading into the background of fougeres for more than a hundred years. The tonka prominent scent has been coming into fashion recently with perfumes like Fève Délicieuse (Dior, 2015, horrible) and Tonka Imperiale (Guerlain, 2010, lovely), but do not look for coumarin’s creamy-vanillic warmth in the insipid musk of Tonka 25.

Oud 27, heaven bless it, has no time for Le Labo’s name game - it is a punch-in-the-throat oud of phenomenal force. Oud perfumes can have many different guises, but this one is firmly in animalic - or ‘barnyard’ - territory. This is due to its pairing with an intensely fecal civet note. There is also a bitter, smoky facet to Oud 27, which is reminiscent of a wheezing car exhaust. Oud 27 is thus the smell of a very dirty and sweaty mechanic stuck working underneath a car on a hot day. There are better oud perfumes such as l’Oudh (Tauer Perfumes, 2018), and better smells-like-a-mechanic perfumes such as Black (Comme des Garcons, 2013), but this one is a fine addition to their ranks. I like Oud 27 because it is challenging, which is rare in niche perfume and even rarer at Le Labo.

Bergamote 22 is a dejected sigh in a bottle. It uses supporting notes to exaggerate the natural facets of bergamot and widen its scope into IMAX - a touch of grapefruit and vetiver to enchance sharp sourness, a little orange blossom for floralcy, musk for that smoky-sweet Earl Grey feeling. All of this is centered around a strong and true bergamot. It smells good for a moment, but much like Fleur d’Oranger and Neroli, Bergamote 22 is not an entire perfume. It is a close-up focus of the top notes of a perfume, which traditional colognes often are - but traditional colognes do not cost $425 for 100ml.

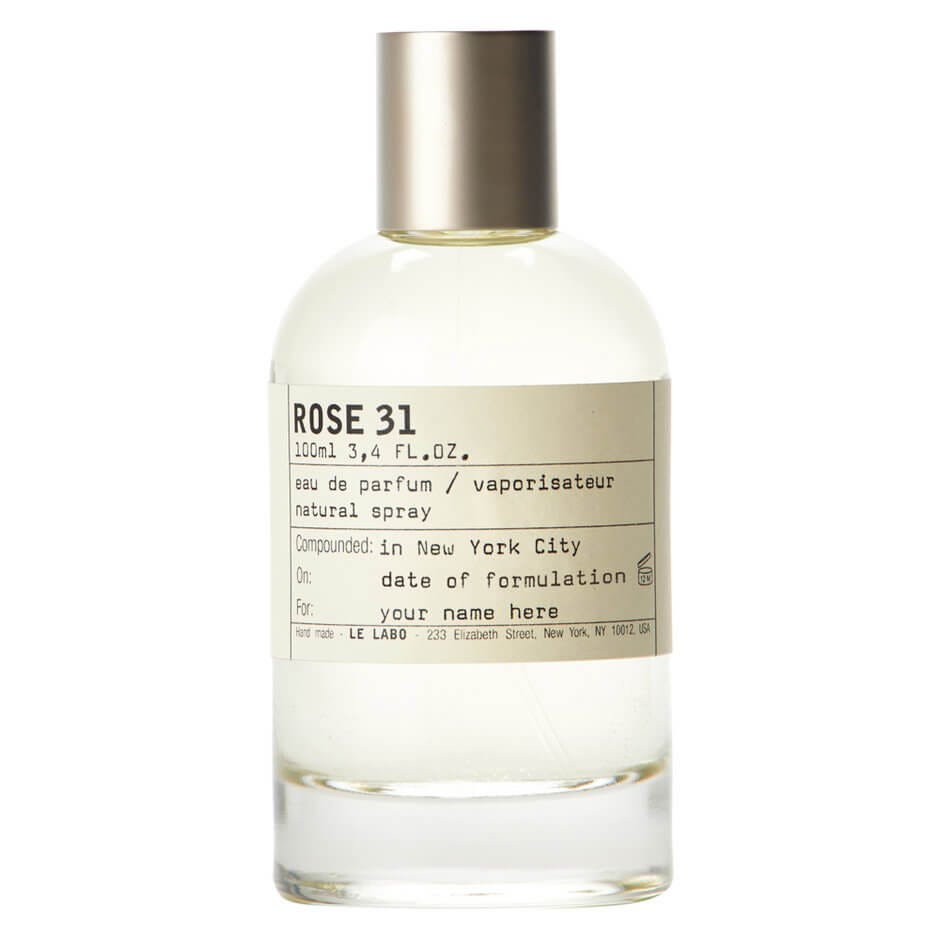

Rose 31 is one of the worst perfumes I have ever smelled. The dominant note of Rose 31 is cumin, which smells earthy and rich to some people and like body odour to others. I am not opposed to cumin in perfumery - its spicy facets are used well in Absolue Pour le Soir (Maison Francis Kurkdjian, 2010), and its sweaty facets are cleverly amped up in the wonderfully fecal Muscs Koublai Khan (Serge Lutens, 1999) and Salome (Papillion, 2015). However, I am opposed to the cumin in Rose 31. It is sour and unpleasantly wet, enhanced by a watery floral note that smells like tepid rosewater spray. The base is a boring cedar buffeted by white musk. Rose 31 smells like a man drenched in sweat who has attempted to clean himself with rose shower gel and failed entirely, leaving the damp floral funk of his body odour to permeate in the steamy bathroom. It is a small mercy that the scent fades quickly; you cannot not smell it an hour after it’s been sprayed. Rose 31 is marketed as remarkable as it is a rose that men can wear. This is nonsense, as men can wear whatever they please, and also because masculine marketed rose perfumes have been around since time immemorial and are especially popular in the Middle East. Rose 31 is one of Le Labo’s most popular scents, and before the release of Santal 33 was their bestselling fragrance. It was composed by Daphne Bugey at Fimenich, who also created Lys 41, Bergamote 22, Neroli 36 and Tonka 25, and collaborated on Scandal (Jean-Paul Gaultier, 2017) and Aura (Mugler, 2017) elsewhere. Rose 31 is a waste of her talent and your time.

Patchouli 24 smells like an open campfire on which meat is being cooked, with an unsettlingly sweet undertone that smells both of scorched hair and a molasses laden barbecue sauce. It is well done for its genre, the burning bacon style of perfumery - one would expect nothing less of its creator Annick Menardo, she of Hypnotic Poison (Dior, 1998) and Black (Bulgari, 1998) fame. Patchouli 24 is dominated by birch tar, a traditional leather note, which melds with vanilla to create an accord that stays for hours and only seems to get stronger and sweeter as the hours pass. The whole thing is overwhelming and sickly on my skin but it is a skilfully made perfume, one of the best in its genre.

Thé Noir 29 is a fig fragrance, and to Le Labo's credit perhaps the most interesting one since Olivia Giacobetti singlehandedly carved out the genre with Premier Figuer (L'Artisan Parfumeur, 1994) and Philosykos (Diptyque, 1996). It eschews the traditionally lush and ripe perfumer’s fig - which is often paired with coconut to exaggerate its creaminess or green notes like galbanum to give it a shot of freshness - for a dry and sharp, almost dehydrated, twist on the note. Fig and tea have been paired in perfumery before, most notably in Fig Tea (Nicolaï Parfumeur Createur, 2007) which bridges the two notes with osmanthus, a flower that is both fruity-leathery and used as a tea itself. Thé Noir is Fig Tea’s dark mirror, sapping its central fig and black tea accord of all colour and lushness until they it is stark and monochrome. It is spare and dry. Thé Noir 29 feels like the olfactory equivalent of a Scandinavian minimalist house where there is almost no furniture and everything is hewn in shades of grey. A spiky cedar-hay base gives Thé Noir 29 its sharp cheekbones. It’s incredibly clever perfumery that uses familiar notes in a novel, abstract way.

Thé Noir 29 was created by Frank Voelkl. He is perhaps equal to Penot and Roschi when it comes to influencing the character of Le Labo as a perfume house, for Voelkl is the creator of the one perfume in the Le Labo catalogue that has risen above all the others in notoriety. He is the man who made Santal 33.

Part Four: Santalum Spicatum

“The perfume you smell everywhere”, says The New York Times, “is Santal 33.”

The perfumes that defined the 2010s all launched early. Aventus (Creed) and Portrait of a Lady (Frédéric Malle) came in 2010, and trailing on their heels in 2011 was Santal 33. This perfume - a combination of cardamom, violet leaf, Australian sandalwood, and ambroxan - would become a cultural touchstone of the milennial urbanite. Santal 33 is “the smell of milennial pink”. Santal 33 has a cult of followers. Fabrice Penot says that Santal 33’s fame “is the price to pay for having created the scent of a generation.”

How did this perfume come to be, and why did it become so popular?

The history of Santal 33’s creation is well documented. The basic story is this: Roschi and Penot worked with perfumer Frank Voelkl of Firmenich on a sandalwood perfume for Le Labo’s initial opening in 2006, but weren’t happy with any of the formulas. They instead used the rough draft of this sandalwood scent to make a candle, Santal 26. When Le Labo first opened the candle quickly became its bestseller, potentially due to word of mouth spreading from its use in the Gramercy Park Hotel; celebrities like Jennifer Lopez would reportedly order huge batches of the candle every month. Penot admitted, “that candle represented about 70 percent of our turnover for the first two or three years.”

Le Labo then released Santal 26 as a room scent, and when Penot smelled the spray on a man in a sports bar he decided enough was enough: they returned to Voelkl to try and perfect the scent for release as a fine fragrance. Voelkl stated, “the candle was paying their rent, but maybe (Penot) wasn’t sure what would happen if they made a perfume out of the scent.”

Voelkl reworked the formula, making it “a little deeper and more comfortable”, and Santal 26 became Santal 33.

The description of the perfume on Le Labo’s site reads:

Do you remember the old Marlboro ads? A man and his horse in front of the fire on a great plain under tall, blue evening skies… A defining image of the spirit of the American West with all it implied about masculinity and personal freedom. This man, firelight in his face, leaning on the worn leather saddle, alone with the desert wind, an icon so powerful that every man wanted to be him and every woman wanted to have him... From this memory is born SANTAL 33: the ambition to create an olfactive form inspired by the great American myth still a source of fantasy for the rest of the world... that introduces our use of cardamom, iris, violet, ambrox which crackle in the formula and bring to this smoking wood alloy (Australian sandalwood, cedarwood) some spicy, leathery, musky notes, and gives this perfume its unisex signature and addictive comfort.

Hidden amidst the usual faff of perfume advertising, we can glean some information about this scent. It’s inspired by the myth of the American cowboy - the myth of America, ‘still a source of fantasy for the rest of the world’. For a perfume and a perfume house marketed as unisex the description points heavily in a masculine direction. The description evokes fire and smoke - cigarettes, bonfires, the leather of the cowboy’s saddle. Its notes include cardamom, iris, violet, ambroxan, cedarwood, and Australian sandalwood.

It’s that last one that is important, because Australian sandalwood is what makes Santal 33 a perfume like no other.

Santalum album, also known as Indian or Mysore sandalwood, is the traditional sandalwood natural in perfumery. Mysore sandalwood has the profile of a woody note but is also creamy, almost milky, and feels warm and intimate. It is the most versatile woody note and has served as a fixative and base note in masculine and feminine perfumes for a hundred years since Bois des Iles (Chanel, 1923). Sandalwood has been used as fragrance before the invention of fine perfumery, back and back to when it was first harvested in the kingdom of Mysore and its oils were used in religious rites.

Santalum spicatum, also known as Australian sandalwood, is drier, sharper, and harsher than its Indian cousin. It is a touch medicinal, with more in common with Atlas cedar or hinoki than Mysore sandalwood. Like the Australian landscape, it is parched and unforgiving. It has less of the lactonic, milky quality of traditional sandalwood and was long considered the inferior species - until Mysore sandalwood became overharvested to the point of endangerment and santalum spicatum was the only choice left for perfumers seeking a natural sandal note.

The sandalwood note in Santal 33 is santalum spicatum. But that does not mean Santal 33 smells of sandalwood.

Upon first spray, Santal 33 is bracing. It has a strange, sharp smell that immediately evokes the kitchen - many people say that Santal reminds them of dill pickles, but to me it smells of yeast. Not yeasted dough, which is a lovely smell, but of yeast itself when you put it in a bowl with warm water to bloom. It's a strange, slightly briny scent - fermented and a little damp. This is an effect caused by violet leaf, a deliciously sharp note made famous in Fahrenheit (Dior, 1989). Violet leaf smells ozonic and watery but also like hot rubber, the way asphalt sizzles on a burning hot summer’s day. Violet leaf smells like someone set a bag of cucumbers on fire. Santal 33 is dominated by violet leaf, and its progression is a study on how the other notes circle around this central violet sun.

This harsh opening lingers for hours but eventually simmers down into its sandalwood heart. It is here, about four hours in, that you begin to understand that if Mysore sandalwood had not been overharvested, Santal 33 would not exist. There is nothing warm or comforting or even sensual about this scent, as there is in traditional sandalwood perfumes.

Instead of using sandalwood in its traditional role as a creamy and milky base note, Santal 33 uses the dry, sharp nature of Australian sandalwood combined with the dryness of cedar to extend the harshness of the violet leaf, giving the scent its characteristic sillage. The genius of Santal 33 is that it uses sandalwood as a harsh element instead of a soft element. It's a masterful twist on the note, and a snapshot of the waiting period between Mysore sandalwood becoming endangered and when it will be harvestable again.

Sandalwood dominant perfumes are a relatively recent trend, gaining momentum with the creation of synthetic sandalwood replacements. Santal 33 is not Samsara (Guerlain, 1989), which uses synthetic sandalwood like Polysantol to exaggerate the natural material and render it in three dimensions; nor is it an elegy for Mysore sandalwood like Dries van Noten (Frédéric Malle, 2013), a mournful perfume centered around the ghost of sandalwood missing in its heart. Santal 33 is a perfume that uses santalum spicatum for its own unique qualities and not as an inferior substitute for Mysore sandalwood.

Santal 33 is my masterpiece on “perfect imperfection.” It completely embodies what I try to achieve as a perfumer, which is purposely overlooking details and the urge to polish every feature to create something that has facets of imperfections that might come off as too much, but all come together to produce something beautiful that has profound meaning.

It is the self confidence of Santal 33, this embracing of the harshness of violet leaf and sandalwood, that has made it a blockbuster. It is the definition of a love it or hate it scent, designed not to fade into the background but to fill a room and turn every head in your direction. To me it does not evoke a bonfire, or the leather of a cowboy’s saddle, or the dream of America. But perhaps there is something of the Marlboro man, the bold and confident swagger of someone who knows without a doubt who they are. Proud of its hard edges: that’s Santal 33.

Le Labo were happy with their partnership with Voelkl: he also created Baie Rose 26 Chicago, Benjoin 19 Moscow, Iris 39, Limette 37 San Francisco, Musc 25 Los Angeles, Tabac 28 Miami, The Noir 29 and Ylang 49 for the brand. Elsewhere in his quest to ensure that all of New York continues to smell of his creations, Voelkl went on to collaborate on another viral behemoth: Glossier’s You (2017).

Santal 33 was the perfect scent for the perfect moment in time: it was the vegan perfume, the sustainable perfume, the ethical perfume. It embodied all the values of the emerging hipster when it launched in 2011. It is a perfume built for the sillage alone, the puzzling way it smells familiar but not, strong but effusive, like the mostly forgotten memory of an argument you once had in the section of the hardware store that is filled with planks of wood.

Santal’s unique sillage, combined with the aesthetic and style of Le Labo, ensured its success would begin to radiate from the inner city to the boroughs to the suburbs, and soon to the entire world. In this way Santal 33 is also the influencer perfume - it is designed to make you remarkable, to draw people in like a bee to pollen, to get them to breathe deep and feel they have no choice but to ask, 'What is that...?'

By 2013, Santal 33 was synonymous with New York and its elite professionals. Jane Larkworthy, who claims that Santal 33 would not exist without her, was beauty editor at the Cut until she was suspended after becoming embroiled in the Bon Appetit scandal. In her article about Santal 33, Larkworthy claims she smeared the candle wax of Santal 26 on herself and used it as her personal scent long before the perfume itself existed.

Santal slowly trickled down from the ranks of the Empire State intelligentsia to become a phenomenon. It is the smell that lingers in the elevator at the Conde Nast office and lurks around coffee carts in front of The New York Times building. It has become a scent that is connected to the nebulous idea of the city, the place where people are effortlessly cool and everyone wears perfume that you’ve never heard of until you muster up the courage and ask.

The entire thesis of Le Labo is that they are perfumes to wear when mainstream perfumery has failed you and your individuality. But in 2015 the New York Times wrote that “Le Labo has, unwittingly, created the most ubiquitous scent in fashion; a signature scent that is so signature you can recognize it in every city in the world”.

Though Santal is an enormous financial success, the company did not quite know what to do when the tables turned and everyone started smelling like Santal 33. In a 2019 interview Penot admitted, “We owe a lot to Santal, but we would also be very happy without it — we have a family of scents we are proud of and are sometimes overshadowed by Santal.”

By 2019, the tide has begun to turn on Santal 33. Like any product that grows from a cult sensation to mainstream success, its ubiquity had robbed it of its appeal. Articles began to come out with names like “Santal 33: The Scent That Went From Ruggedly Cool To Utterly Basic”. The scent that had once been a byword for inner city professionals could now be smelled on mothers at the school drop off, on cashiers at the grocery store, in every crowded train carriage on every morning commute on the planet. What had once been coveted was now mundane.

Penot commented, “It’s interesting to see how the underground crowd, after once having used Santal to feed their coolness, now hate the fact that it is no longer theirs only, so now it’s cool to deny it.”

The fashion world and urban hipsters and New York intelligentsia will always move on to another perfume, but Santal 33 will remain a snapshot of the 2010s. It is an olfactory time machine back to the drinks with friends, the bad Tinder date, the Game of Thrones finale, the vacation at the fancy hotel. It is the smell of the chaos of the populist era, the perfume you wore during the Brexit referendum and when Trump won the election.

This is how perfumes come to define a point in time, a social movement, an epoch: like Shalimar (Guerlain, 1925) in the 1920’s and Poison (Dior, 1985) in the 1980’s, Santal 33 in woven into the fabric of the 2010’s, the scent of the urbanite, of social media and oat milk lattes and milkshake ducks. It is the scent of stratification, in society, in perfume, in who can afford to buy luxury and who can boast about it on their feed. It is, along with Aventus, the embodiment of niche perfume.

Commenting on Santal’s legacy, Penot says:

Santal is unleashed by now, our child has become an adult and lives its own life. It could very well become the next Chanel No. 5 in the history of perfumery. That's not being pretentious — it has nothing to do with us anymore, and frankly tells more about luck than our own talent. You can't make Santal without what my friend Isaac called 'a stupid amount of luck.' It is its own thing and it will follow its own legend, whatever it becomes we'll be ok with it.

Santal 33 released in 2011. Le Labo was acquired by Estée Lauder three years later in 2014, for a rumored $50 to $60 million.

PART FIVE: Dancing in September

The other half of Le Labo’s perfume catalogue are a group of perfumes called the City Exclusives. These are scents named for and inspired by cities that host Le Labo flagships, and can only be sampled and bought at the store in that city for most of the year. City Exclusive perfumes are available worldwide only in September.

The theory behind the City Exclusives is to capture a ‘cultural experience’, as Penot explains:

When we traveled, we were kind of fed up to find the same stores in LA, Tokyo, Paris. We wanted to add a cultural experience that you would not be found anywhere else. Now that we have stores in the main capitals of the world, the risk is becoming the exact thing we were resisting in the first place. How to fight that? Making sure that the experience is not uniform everywhere — in the stores but also in the perfume collection. That's the reason we created the city exclusives where a specific perfume honors the city we are in and will not be sold anywhere else (except one month a year), defying any business return but feeding our initial intention.

The City Exclusives line operates as a kind of niche line within a niche house: Le Labo but nicher. These perfumes sell at an astronomical $718 for 100ml.

The City Exclusive line includes Aldehyde 44 Dallas, Baie Rose 26 Chicago, Benjoin 19 Moscow, Bigarade 18 Hong Kong, Citron 28 Seoul, Cuir 28 Dubai, Gaiac 10 Tokyo, Limette 37 San Francisco, Mousse de Chene 30 Amsterdam, Musc 25 Los Angeles, Poivre 23 London, Tabac 28 Miami, Tubereuse 40 New York and Vanille 44 Paris.

Of these perfumes, a depressingly large number are simply ideas from the signature line that have been twisted and embellished slightly: Gaiac 10 is Baie 19 in another outfit, Baie Rose is Rose 31 on a good day, Aldehyde 44 is the Hyde to Ylang 49’s Jekyll, Musc 25 is every ambroxan drydown of every Le Labo perfume, Tabac 28 is Patchouli 24 with less vanilla and more arrogance, Tuberose 40 is a combination of Fleur d’Oranger and Jasmin 17, and the less said about the citruses (Bigarade 18, Citron 28, Limette 37) the better.

The only city exclusives of note are Mousse de Chene 30, Vanille 44, Benjoin 19, and Poivre 23.

Mousse de Chene 30 stumbles close to interesting without ever fully tripping in. The dominant note in the scent is clearwood, an incredibly loud synthetic patchouli. But underneath that it is a chypre, dank and mossy and a little vegetal. Mousse de Chene then turns around and debuts a strange bay leaf note in the mid that makes you think of bubbling ragu. It is an odd perfume, and therefore interesting, but not very wearable - you feel as if you’ve dunked your wrist in the simmer sauce.

Vanille 44, created by perfume superconductor Alberto Morillas, is not a vanilla in any sense of the word. It is a dry and papery perfume which uncouples vanilla from any sort of sweetness and uses it in the base to deepen what is essentially the smell of old books. There is incense here, too, and the overall feeling it evokes is of an attic library in a church in Neuilly. Vanille 44 smells like a beam of sun shining into an old room and turning what once was empty space into a slice of light filled with swirling dust.

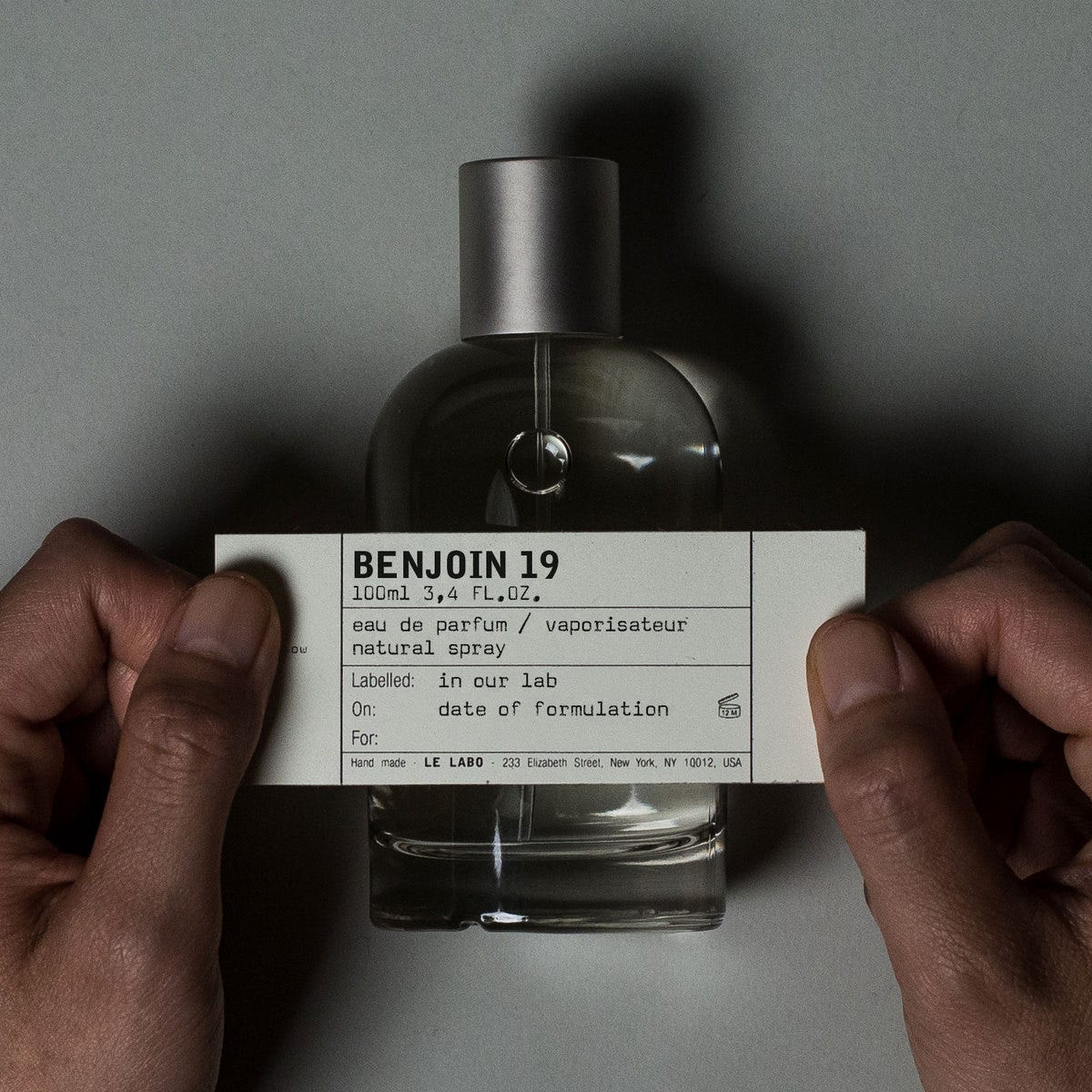

Benjoin 19 is quite similar in profile to the gone but not forgotten Sahara Noir (Tom Ford, 2013), a gorgeous amber-incense. Benjoin opens with a blast of benzoin enhanced by stark frankincense, but is kept from thurible territory by a burning wood fire sort of sweetness similar to Un Bois Vanille (Serge Lutens, 2003) and its wildly popular stepchild, Replica: By the Fireplace (Maison Martin Margiela, 2015). It is a clever perfume that highlights the way that benzoin can act as a bridge between the smokiness of resins and the sweetness of gourmand notes. It dries down to a lovely incense-amber, more vanilla than benzoin but still warm and creamy on skin. It lasts for a few hours and projection is little to none; it is a good perfume, but there are too many similar to it at astronomically lower prices to make it worth your time.

Poivre 23 is a pepper fragrance, both in name and execution. I have a soft spot for pepper in perfume - I am even a fan of pink pepper, a much derided top note that has been gaining in notoriety for a decade or two. I am predisposed to like Poivre 23 and I do at first spray; the pepper note is full bodied and rich, the precise scent of black pepper ground fresh over a bowl of pasta. The problem with pepper notes is that like citrus, they do not last. This opening cacio e pepe gambit quickly morphs into a dry vanilla, similar to Vanille 44, with a twist of labdanum to try and keep your interest. It only lasts an hour or two on skin. Poivre 23 is the passionate lover who sneaks out before dawn; you always wish they would turn it around and stay the night, but you know deep down they will always disappoint you.

The City Exclusive line is successful: the scents almost always sell out when they become available worldwide in September, and in their home cities are often bestsellers.

But the City Exclusives line is niche perfumery at its most uninventive and cynical. The issue is not what the consumer will pay - what you value in perfume and what you are willing to spend is your business - it is what the brand sells the product for. Unless they contain rare or hard to harvest naturals, there is only one reason to charge so much for a perfume: to price people out of the product. It is a miserly way to sell fragrance, one which even the highest priced designer houses do not stoop to - they may have their exclusive lines, but the pillar scents of Chanel and Dior can still be bought for around $150 for 100ml.

Penot is aware of the issue:

"There is almost no economies of scale in what we do. In a way, you're getting a deal, because we're not 40 times more expensive than a $60 fragrance. Obviously, you need to be able to afford our perfume. I understand not everybody is able to, which is kind of a fail of ours."

Luckily, the City Exclusives line contains nothing worth your time or your frustration over the cost: they are all a kind of a fail. If you live near one of the lauded Le Labo stores with an exclusive scent, make the pilgrimage and smell for yourself.

PART SIX: Overheard at Le Labo

Alongside their offical instagram, Le Labo runs Overheard At Le Labo. This is an account which offers “spoken words from our Labs. Recorded on one of our pretentious vintage typewriters.” The ‘lab’ is a Le Labo stand or store, and the overheard statements include things like:

‘She’s Rose 31 in the sheets and Santal 33 in the streets.’ ‘Lock that down.’ \Yonge Street. Toronto.

Soul: “Do you know which fragrance your girlfriend likes?” Man: “Well, our Wifi password is Bergamote 22.” \Capitol Hill. Seattle.

(A soul is an employee of Le Labo.) The account is popular, with over 70 thousand followers, and is the closest to advertising that Le Labo gets: the account seeks to curate the idea of who Le Labo customers should be in a quirky, irreverent way.

Overheard at Le Labo reinforces the emphasis the brand places on the physical in perfumery. Shopping and buying at Le Labo is not meant to be a chore but an experience. In their ‘immersive’ stores, the main experience Le Labo sells is to mix the perfume you buy right before your eyes. What is meant by this? According to a press release from the brand:

When customers buy one of Le Labo's scents, a maturated essential oil blend is mixed with alcohol and water to create a finished fragrance. The process is designed to take about 10 minutes, ample time for visitors to browse shelves of raw ingredients in the 600-square-foot shop...

The perfume is not mixed, then, but rather diluted into its bottle. This is an ingenious marketing gimmick that solves one of the greatest issues in selling perfume: everyone wants to smell individual, but they still want the perfume to smell the way it did when they first smelled on someone else. What all of humanity truly desires is for their favourite perfume to be made for and used only by themselves, but this is rather unfeasible economically.

Le Labo perfumes are a corps lineup, an army; the same bottles sold for the same price, no matter the difference in formula cost. There is something forbiddingly bureaucratic about them, fragrance envisioned by Kafka. And yet Le Labo wants uniformity and individuality at the same time: they mix the perfume in front of you, they write your name and the date on the label. Unisex and characterless - but personalised. Once you have bought a perfume, you are part of Le Labo and it is a part of you. Le Labo bottles are a blank canvas that your name has literally been written on.

By having the perfume diluted into the bottle in front of the customer Le Labo seeks to make them feel that their perfume is somehow different or special by connecting it to an experience. The reality is that a perfume blended in-store is the equivalent of soft drink syrup being mixed with carbonated water in the drive-thru at McDonalds. Le Labo have accidentally invented the post-mix perfume.

Co-founder Edouard Roschi says that a Le Labo store:

“looks and functions like a perfumers lab. You can see the perfume model being blended, you can smell the ingredients that are sitting on the shelf, you can see them in their different states. You’re welcomed by our lab technicians who are experts in blending and the presence of the perfumer is felt through the setting itself, the beakers and bottles.”

I live in the hinterland of a Le Labo store. It is about two hundred kilometers from me, tucked on a backstreet near Bondi Beach in Sydney - the place where famous people stay when they make the fourteen hour flight from Los Angeles to Australia. It took four hours to get there from my home, which I did happily because I am an obsessive who is very used to doing silly things for perfume.

The Le Labo is wedged like an afterthought between a carpark and a garage door. Down the street and around the corner is the ocean, and the store is close enough that you can still taste the salt in the air as you walk by. The exterior of Le Labo looks like it was built for the Diagon Alley set on the Harry Potter films - it even has MANUFACTURERS OF FINE PERFUMERY written in Victorian style font above the door. It’s a style that would be at home in Nolita, or London, or even fifteen minutes away in the steel grey city centre of Sydney, but in laid back Bondi it sticks out like a goth sulking in the food court at the mall.

The store is so purposefully meant to evoke urban decay that it makes you wince; its interior does indeed feel like an abandoned sanatorium. The walls are covered in sporadic, dirtied white tiles and every fourth or fifth one is purposefully shattered; the overhead light is clinical and buzzes like it’s heralding the arrival of a monster in a horror film. The front counter/centerpiece is an apothecary-style wooden console with a hundred tiny drawers. There is a cage in the corner with huge glass bottles full of vetiver root and oakmoss arranged artfully around digital scales and empty beakers - presumably where the souls of Le Labo do their diluting.

There’s a huge tan leather chair in one corner that looks like no one has sat in it since the fall of the Berlin Wall. It is kept company by a gigantic cement candle propped on wooden crates meant to resemble disposable cardboard boxes.

The candles are kept under cloches and the perfumes have blotters behind them stamped with their name in faux-typewriter font on one side and a list of notes on the other. I like this - after you spray more than three blotters you forget which is which, so Le Labo has spared me the step of writing on every one.

What I loved most about Le Labo when I visited was this: in that Soviet sanitorium store there was a little wall of vials that weren’t for sale. I approached them and read the labels, my eyebrows raising higher as I went: bergamot absolute, ambroxan, cashmeran, vetivert, birch tar… These were dilutions of actual perfumery ingredients and accords, not essential oils but the kind of thing you would order in bulk from a perfume supply store or a fragrance oil company. There were two dozen of these little amber bottles, all with painfully hipster labels meant to look like they’d been made on a typewriter.

Looking at them, I felt a joy light up my face like it was Christmas morning.

A sales assistant approached me in my rapture. ‘Can I help you with any of the perfumes?’

‘No,’ I replied cheerfully. I pointed to the ingredient bottles. ‘But can I smell these?’

She seemed very uncertain but ultimately agreed, and I happily began unscrewing and smelling, asking her if I could dip a blotter in a few of the more interesting scents. I had smelled more than fifty perfumes that day, and the most interesting and complex thing I took home on my blotters was a dilution of styrax from Le Labo.

The ingredient display at Le Labo is par for the course in their deconstructed perfume concept, the ‘we mix your perfume in front of your eyes!’ gimmick. But there is merit to this - however hipster in their execution, Le Labo is attempting to educate the consumer about the guts of perfume, how the sausage gets made. When they are not misdirecting people with a perfume called Tonka that smells of cedar and musk, the sentiment is admirable.

Music is playing in the background - alt-J, Tame Impala, the Twin Peaks theme, some Serge Gainsbourg for a little fine French perfume flavour. The ambiance is completed by the scent of violet leaves and synthetic woods - either Santal 26 is burning or Santal 33 is being filtered through the air system, because that familiar woody-ozonic-yeasty smell surrounds me as I walk through the store. I know that some perfumeries like to pump scents through the air conditioning system - Penhaligon’s famously blasts their odious Halfeti onto the street in front of their stores like a diabolical witch luring children with candy - but it has always seemed odd to me to begin burning people’s noses out before they even start sniffing the products.

Everything in the Le Labo store is meant to look like it was salvaged or upcycled, as if the salespeople stumbled upon a store and just started hawking their wares one day. When you walk through the real estate of Le Labo, the carefully constructed shambles, you understand why Roschi and Penot claim to have been inspired by wabi-sabi. A Japanese cultural movement, wabi-sabi is defined as:

the Japanese art of finding beauty in imperfection and profundity in nature, of accepting the natural cycle of growth, decay, and death. It's simple, slow, and uncluttered - and it reveres authenticity above all. Daisetz T. Suzuki, who was one of Japan's foremost English-speaking authorities on Zen Buddhism and one of the first scholars to interpret Japanese culture for Westerners, described wabi-sabi as "an active aesthetical appreciation of poverty."

Nobody at Le Labo seems concerned with politics of appropriating the aesthetic of urban decay - of poverty - for a luxury perfume brand. It is a style meant to appeal to the consumer who lives in a Le Labo city, an exclusive city. It is based on the idea that poverty is authenticity because no one would choose it if they could have something else - in other words, selling Detroit to San Francisco. Commenting on how Le Labo chooses the cities for its stores and exclusive perfumes, Penot says:

“At the beginning, it was where we liked to go — and wanted to go personally. Now it is a little more rational: We ask ourselves if there are enough people with our style in this city to make it worth going.”

When you walk through a Le Labo store, it does what it is meant to do: it feels like a place made for people who have $425 to spend on a perfume. Because the only people who would have an aesthetical appreciation for poverty are people who have never been in poverty. Le Labo is perhaps the most inauthentic, unnatural, and soulless perfume store I have ever visited.

Nothing about Le Labo is natural in the same way that nothing about perfume is natural: it is entirely man-made, alchemy conjured from chemicals and chromatographs. Even natural perfumery is about manipulating scents to blend together, not embracing them in their natural cycle. Thus a wabi-sabi perfume cannot exist, and the core thesis of Le Labo is at odds with itself: it is about celebrating the beauty of imperfection but the scents take over two years to perfect, and no one wants to pay so much for something that is purposely flawed.

As I smelled my way through the Le Labo store, a woman came in and bought a perfume. She didn’t waste any time or smell a single thing: she wanted a 50ml bottle of Bergamote 22, a birthday gift for her daughter. After processing the sale, the soul asked what name she wanted on the label. The woman gave it. The soul told her that he would blend the scent immediately.

‘Oh,’ she said. ‘You don’t have one you can just give me now?’

‘Sorry,’ said the soul. ‘We blend all of our perfumes to order.’

‘How long will it take?’

‘Ten minutes or so.’

‘Well,’ said the woman. ‘I have to buy some groceries. Do you mind if I come back?’

PART SEVEN: Soul

What is Le Labo’s place in the wider fragrance landscape?

Fifteen years after Le Labo’s founding, niche perfume has cut a swathe through the fragrance market. If niche truly is the new black, it represents an opportunity to go beyond the limitations of the traditional perfume - and niche brands are priced as if their offerings are better than designer houses. Jo Malone and Frédéric Malle, in their own ways, did present novel ideas to the perfume market: simplicity and artisanship respectively. But what does Le Labo bring? Are their scents truly so remarkable to cost what they do? Is there any perfume in their line - even the behemoth of Santal 33 - that wouldn’t be perfectly at home in Armani Privé?

Le Labo was made in New York, 'shaped by New York', but given a French name presumably for a connection to the long history of French perfumery - where most of their scents are created by perfumers at the fragrance firms anyway.

The shape and character of American perfume is not being crafted by two former Armani executives commissioning scents from French firms. Independent American perfumery is entering what may be its golden age. Dawn Spencer Hurwitz, Kyse Perfumes, Matriarch, Sixteen92, Sarah Horowitz, January Scent Project: these are houses with self taught perfumers who are defining what American perfume can be outside the lens of France and the great fragrance houses.

None of Le Labo’s perfumes were composed by an American. Can they truly be called an American house? Underneath the brand name on the website they proudly declare GRASSE - NEW YORK, as if the company has any connection to the historical perfume culture in the south of France. (Le Labo does not even have a store in Grasse).

A term that Le Labo uses often is slow perfumery:

“We work with a community of craftswomen and craftsmen who contribute to and shape our world: the perfumer, the lab technician, the candle pourer, the rose harvester. We work to make the lives of people more beautiful by creating unique sensorial experiences, and our craft is deeply rooted in slow perfumery.”

From my understanding this is an appropriation of the term slow food, a movement born in opposition to fast food that supports farm-to-table local food culture. If we apply this concept to perfumery, surely “fast perfume” would be the institutions that churn out constant designer flankers and celebrity scents? That would be the large fragrance firms, Givaudan and Firmenich and Symrise and IFF… who Le Labo have collaborated with on all their perfumes, and whose ingredient sourcing supply all of Le Labo’s product. Le Labo are not a house with their own ingredient supply line, like Chanel and Dior - barely any houses are. Roses ‘hand-picked in Bulgaria and Grasse’ for Rose 31? Certainly - en masse on a Firmenich farm.

Le Labo is not quiet perfumery, the gossamer creations of perfumers like Olivia Giacobetti that speak clearly but softly; it is not minimalist perfumery, the style heralded at Hermes by Jean-Claude Ellena using a reduced palette of notes to create scents that are somehow complex and simple at the same time. This is slow perfume, ethical perfume, hand poured perfume - boring perfume. It prides itself on having nothing to say.

Le Labo has concerned itself with authenticity. But Le Labo hasn’t risen from nothing to become great - it was never really given the chance to fail in the first place. It is a brand begun by perfume industry insiders, given access and coverage by the industry, and eventually bought out by Estée Lauder, a goliath in the industry. Nothing about Le Labo is artisan, bespoke, or slow.

Ethics will only take you so far in perfume. At the end of it all you must trust your nose and only that. Despite the brand’s aesthetic I know that if I truly loved a Le Labo perfume, found it moving or artistic or memorable, I would buy it.

But I don't think about Le Labo perfumes very often. They don’t linger in my mind. Sometimes I puzzle over Santal 33 and the place it has taken in the halls of perfume culture. I think about Thé Noir 29, conjuring up the scent, and then my mind moves on. I don't crave to smell any of them because they don't make me feel. The one that came closest to an emotional reaction was Vetiver 46, and that is because it is a skeletal Comme des Garcons Man 2. When the Le Labo perfume dies it does not become a ghost; it has no unfinished business. It does not haunt you. And I want perfumes that hound at me the way Orestes was chased by the Furies.

Does Le Labo have a Guerlinade, a secret accord that simmers in the base of every scent and secretly unites them so that even if you don't know what you're smelling, you know it is Le Labo? The scents are wide-ranging, from the funk of Labdanum 18 to the diffused nothingness of Another 13, but I believe they are all connected by an accord in the drydown. The Le Laboade is a skeletal and cedary thing, ambroxan mixed with something sour and tannic, the drydown of Thé Noir 29 writ large. It is sharp and bony, like a loft room that has had the ceiling stripped away so the wooden beams are exposed. Le Labo must be praised for consistency: this accord is the olfactory equivalent of the aesthetic in their stores.

This is the scent of minimalism, Le Labo style, the neutral that they believe their pharmaceutical bottles and warehouse-apothecary stores provide. I think it is good that the perfume industry is moving beyond gendered marketing, but when I smell Le Labo perfumes I wonder why in sacrificing gender these perfumes have also sacrificed personality.

There is no warmth in the Le Labo perfume. There’s powder (Patchouli 24), and funk (Labdanum 18), but nothing of warm roundedness of an amber - or heaven forbid the vanillic sugar of a gourmand. This is not an inherent defect, but it’s interesting to me: the most commonplace and easy-to-please genre of perfume is something Le Labo has no interest in. Nor do they have a traditional fougere in their lineup, that lavender-oakmoss-labdanum accord that is the most masculine of perfume styles.

But Le Labo are not determined to eschew all traditional perfumery: Mousse de Chene in the City Exclusives line is a chypre in the style of the grande dame Mitsouko (Guerlain, 1919); Bergamote 22 is a classic cologne; Ylang 49 is a screeching aldehydic floral in the 1970’s style. Then I thought ah, it’s that they don’t want to release perfumes in styles that are popular now. But this too isn’t quite accurate: Le Labo embraced the agarwood trend with Oud 27 and the musky not-a-perfume with AnOther 13.

Another defining characteristic of all Le Labo scents is that they are linear. They are not designer scents crafted to be top heavy, with an enticing opening blast that quickly morphs into a depressing drydown: the Le Labo perfume is the same from top to bottom, the whole thing fading away over time like a screen going dark at the end of a film. They do not develop or tell a story: they are a haiku, short and succinct. Wearing a perfume that develops feels like being lead through the undiscovered country: you don’t know where you’re going but it is an adventure to get there. Wearing a Le Labo scent is like looking down at a city from on high: you see everything in one snapshot, no surprises waiting.

Le Labo is the olfactory message of the hipster movement writ large: an attempt to seem effortless that in fact takes more effort than something earnest and genuine. We simply found the building like this, stripped back and industrial (of course we didn't refit it to match our aesthetic); our perfumes are predominantly natural, with expensive formulas (we did not use a vat of synthetics to make a perfume that smells like dehydrated fig and pencil shavings). It is about going back to the basics, back to nature - but the perfumes are heavy in synthetic musks, so they are mostly unnatural. Le Labo: marketed as natural and complex, composed as synthetic and disappointingly linear.

When I wear a perfume I do not want it to effortlessly become part of my body, my skin but better - I don't want people to think I'm not wearing a perfume at all. I wear perfume to change my mood, to shape it. I want to wear perfumes that make a statement. It doesn't have to be bold, but it should have clarity: whatever a perfume is attempting to do, be it a chypre or cologne or fougere, it should try and do it well. Santal 33 has this clarity, as does Vetiver 46 and even Ylang 49 - but none of the other scents in Le Labo’s lineup do. This nonchalance - fragrance for people too cool to care - is what keeps Le Labo from true greatness in perfumery.

What I find most admirable about Le Labo is that they had an in house sample service that offered small sizes, fair prices, and free shipping long before COVID-19 made discovery sets more commonplace. This service is available from all their stores - they are one of the only niche houses on my continent that is truly accessible. Le Labo sells their scents in 15ml, 50ml, 100ml, and 500ml flacons; every perfume can be bought in EDP, liquid balm, travel spray, solid perfume and perfume oil form. Perhaps it’s just a way to try and amp up sales, but Le Labo has touched on a concept that is important to me: perfume should be accessible to everyone.

The role niche perfumery seems to play in the greater fragrance world is to get people interested in scent, in thinking about what goes in to what they’re wearing. High visibility is key to these brands and their success - I can’t tell you how many people I have spoken to whose interest in fragrance was sparked by the Maison Martin Margiela Replica stand at a Sephora. This phenomenon, the niche brand as a sort of gateway to fragrance, is an excellent thing. We are in the era of the informed consumer - people want to research the brands they’re buying from and the beauty products they use, they want to hear what other people are saying.

If you are interested in fragrance at all, I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend buying a few Le Labo samples or making the pilgrimage to a store if there is one near you. Get your hands on this stuff, spray it on the blotter and on your skin, think about it, feel about it. See if you can spot the ingredient the scent is named after, look up the note list to see what you are really smelling. If you are in the store, ignore the purposefully broken tiles and the city exclusives and ask to smell the accords and ingredients in the little amber bottles on the far wall.

Then keep reading, keep exploring, keep smelling. It’s an investment that gives many returns. You may not find them at the Le Labo store but there are thousands of perfumes out there, eager and waiting to haunt you. ◙

References and Further Reading

All prices are current to the Australian dollar as at May 1, 2021.

¹ Page 80, “The Perfumes: The A-Z Guide.” Turin, Luca; Sanchez, Tania (2008)

There are no quotes pulled from it, but The Naturals Notebook: Sandalwood by NEZ was incredibly helpful for much of the Santal 33 segment of this article. NEZ is a collaborative project with fragrance oil house IFF.

Le Labo famously ‘do not advertise’ - but they are fond of doing interviews and collaborating on features in high end newspapers, a kind of advertisement in itself.

New York’s Cult Fragrance Wouldn’t Exist If It Weren’t for Me (Le Labo Santal 33: A History)

Cult perfume brand Le Labo and the chemistry – personal and actual – behind its success

Interview with Senior Perfumer Frank Voelkl of Firmenich + Le Labo

If you are interested in more of my writing on perfume, here is my deep dive on Chanel’s Le Lion and here is my Cultural Autopsy of the Celebrity Perfume. I post weekly dispatches and other articles such as this one on this Substack, and can be found talking about perfume on twitter and Instagram. If you read this far, thank you.

this was such a good read! i’d love read your thoughts on Byredo or Comme des Garçons Parfums

So many descriptive joys in one piece! Savoring each one makes me feel like a child gleefully allowed to stomp in puddles on a rainy day. Brava!