A Cultural Autopsy of the Celebrity Perfume

Celebrity perfume is dead. Long live celebrity perfume.

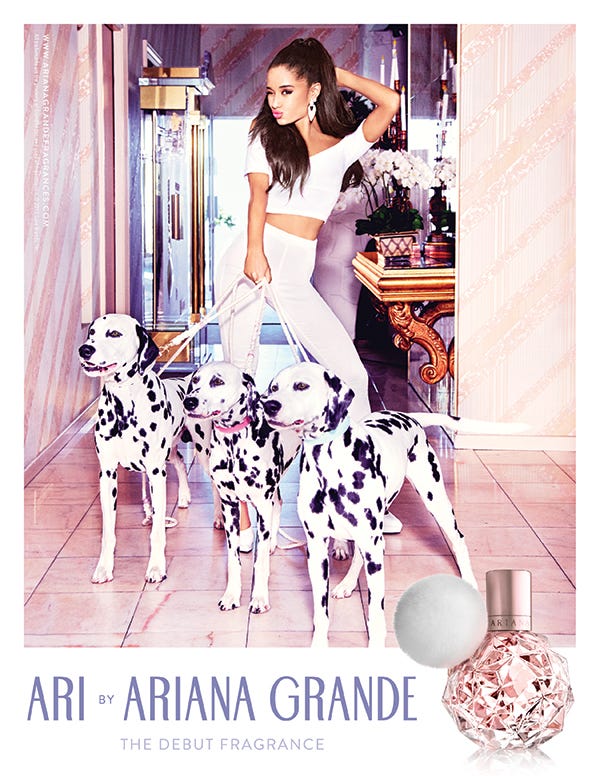

In Australia we have a discount chemist that runs a fragrance grey market. They sell Chanel and Dior and other designer scents at dramatically reduced prices. In the fragrance aisle, the designer perfumes are locked behind glass and you have to beg a sales attendant if you want them sprayed on a blotter. On the other side of the aisle, however, are perfumes on open shelves that you can spray whenever you like. There’s perfumes from Sarah Jessica Parker, Jennifer Lopez, Ariana Grande. Nothing on these shelves costs more than $50.

In the fragrance world, you’re either a brand they keep in the glass cabinet or you’re not. And if you’re not, you’re mostly likely a member of an endangered species: the celebrity perfume.

If you were a teenager in the noughties, you are intimately familiar with the celebrity perfume. You were the target demographic, and you either bought many bottles or had them bought for you. Smelling any celebrity perfume is like stepping back in time to the 2000’s; the decade lives on in Lovely (Sarah Jessica Parker, 2003), Miami Glow (Jennifer Lopez, 2005), and Fantasy (Britney Spears, 2005).

The golden age of the celebrity perfume ended with the global financial crisis and the rise of the social media celebrity. Tania Sanchez writes,

“Celebrity perfume is effectively over. It gives us great pleasure to toll the bell for these cynical fame-monetization strategies. Historians of the future, know that in the first decades of the millennium there was a yearning on the part of the public to consummate their love affair with the famous by buying, as a form of tribute, cheap perfumes with celebrity names. I was relieved to read in the trade news that UK sales of celebrity fragrance had dropped twenty-two percent in 2016 alone, and that US sales had been dropping steadily since 2011.” ¹

But is the celebrity perfume truly dead? Framing Britney Spears, a documentary examining the legal conservatorship imposed on the singer, debuted on February 5, 2021. It ignited a conversation about celebrity, sexism, the 2000s, and what it means to be a woman in the limelight — Spears being at the nucleus of these issues. After Framing Britney Spears aired, sales for the singer’s perfumes increased by 155%. When the reboot of Sex and the City was announced in February 2021, sales of Sarah Jessica Parker’s perfumes also saw a massive jump. There are new celebrity lines being launched — and succeeding — in the Instagram era.

The rise and fall of the celebrity perfume is about fame, classism, sexism, who gets to smell good and who decides what smelling good means. But before everything else, it is a murder mystery: if the celebrity perfume is truly dead, who killed it?

PART ONE — MY NAME IS OZYMANDIAS, KING OF KINGS

Elizabeth Taylor killed the celebrity perfume.

Some people will say the first celebrity perfume was Sophia (Coty, 1980); some will say it was Uninhibited (Cher, 1987). They are both good answers. The right answer, of course, is that the first celebrity perfume was Chanel №5.

№5 is a hundred years old in 2021. Chanel may credit its combination of aldehydes, florals, and sandalwood as the reason for its ongoing success, but №5 would not have the reputation of le monstre today if it had not been for Marilyn Monroe. The infamous interview where Monroe said she wore a few drops of №5 to bed was in 1952. After that came L’Inderdit (Givenchy, 1957).

L’Interdit was the first fragrance with a ‘face’ — a celebrity who endorsed it in advertising. And what a face — L’Inderdit was commissioned by Hubert de Givenchy for Audrey Hepburn. I have only smelled vintage L’Inderdit in passing (the name has since been given to a new Givenchy scent — what is sold today as L’Inderdit has nothing in common with the original), and it was a strongly aldehydic fruity sandalwood, more than a little similar to №5. It is powdery and elegant but not delicate or wan, with a strong woody base. It is the smell of Audrey Hepburn joyfully running around Paris in Funny Face, a breath of fresh air in a city laden with tradition.

Perfume “faces” still exist today for the majority of designer brands, but a celebrity creating their own perfume never succeeded until Elizabeth Taylor. The actress released her first perfume, Passion (Elizabeth Taylor, 1987) with the backing of beauty conglomerate Elizabeth Arden. The scent was sent out as a brief for the fragrance oil houses, like the majority of designer perfumes were and still are. This business model — the celebrity branded perfume line being managed in the shadows by a larger conglomerate — would be the example every celebrity fragrance brand would follow.

And they followed it because it worked. With Passions and especially White Diamonds (Elizabeth Taylor, 1991) Taylor proved that with the right star and the right scent, a celebrity fragrance brand could be an enormous success. Upon her death in 2011, Elizabeth Taylor had an estimated net worth of 800 million dollars, the majority of it from her perfume brand. She famously claimed that her perfumes earned her more than all of her film roles combined.

And here is the genius behind Elizabeth Arden’s management of the Elizabeth Taylor brand — the scents are all affordable. They were not designed to be — White Diamonds originally retailed for $200 a bottle — but the scents quickly found a home at discounters and chemists, and from there onto the dresser of every woman in the early 1990’s.

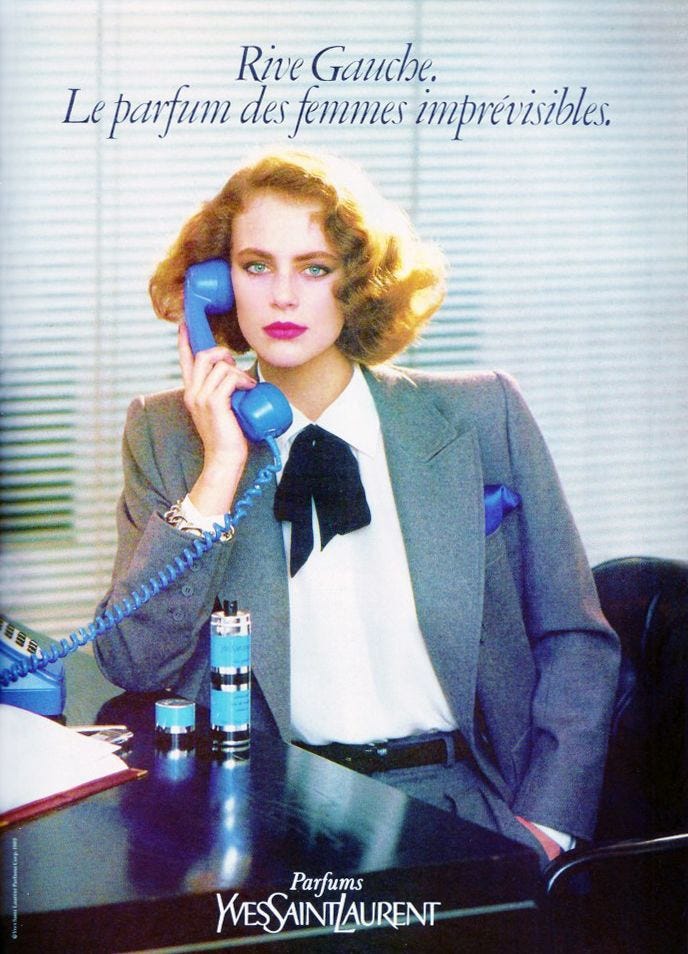

White Diamonds still sells (in the chemist; not behind the glass). And it is a powerhouse of a fragrance, the 1980’s in a bottle, eau de Dynasty. A huge aldehydic tuberose, it is as if someone had spliced the opening of Rive Gauche (YSL, 1971), the heart of Poison (Dior, 1985) and half of Chanel’s catalogue into one fragrance, halved the formula cost, and turned everything up to an ear splitting decibel. White Diamonds is garish and magnificent. It has personality, the most important thing for any fragrance to possess. White Diamonds is crucial proof that when possessed with clear vision and creative direction, even a celebrity scent with a low formula budget can be a triumph. Perhaps only wearable by the smothering aunts of the world, but still a triumph.

The gold standard had been set. Elizabeth Taylor was the first successful celebrity fragrance franchise, and she set the precedent: lower priced scents released under celebrity named brands that were owned and managed by a larger conglomerate. The majority of successful celebrity scent portfolios today are managed by Elizabeth Arden (bought out by Revlon in 2016), Coty, and Designer Parfums. No celebrity scent in the 2000s was an independent brand.

In an interview for NPR the vice president of Coty said “The beauty of a celebrity, unlike a designer brand, is there is consumer knowledge of this brand or product from the moment you hit the counter. Having one of those names on a bottle saves millions of dollars in advertising.”

The next great leap in celebrity perfumery was Glow. Jennifer Lopez was having quite a time in the early 2000’s. After inventing Google Images she decided to try her hand at perfumes, and debuted her first scent Glow (Jennifer Lopez, 2002) at Trump Tower (!). The scent made $100 million in its first year.

Glow is a very strange perfume. I admire it even as my nose shies away from the blotter. It opens with a very sharp green floral, a brutally loud combination of jasmine and the sharp facets of grapefruit, which lend a bit of citrus freshness but mainly smells acidic. It then swoops straight into the drydown, a scent which I can only describe as the smell of sunscreen. Not perfumery’s usual sunscreen accord, which is a horrid coconut oil and sugar thing, but actual sunscreen, balmy and kind of ozonic with a touch of musk. Glow is the smell of SPF 50 sinking into your pores. It’s a picture perfect, if somewhat unexpected, scent of summer holidays.

Après JLo, le déluge: from 2002 until 2010, celebrity perfumes would multiply exponentially. Soon it seemed like everyone had a perfume. Jennifer Aniston and Bruce Willis both gave it a go; brands and universities and even the 45th president of the United States jumped on the bandwagon. The majority of these scents were complete failures. The ones that weren’t spawned perfume empires and became huge earners for their celebrities.

In the space of a few short years, celebrity perfumes had completely saturated the market. They were flying off the shelves, but nobody could understand why - celebrity perfumes, everyone agreed, smelled terrible.

Chandler Burr, once the perfume critic for the New York Times, infamously gave Midnight Fantasy (Britney Spears, 2012) a four star ‘excellent’ review. The review points out that:

“Celebrity perfumes occupy a decidedly downmarket place in perfume…In other words, if you had money and, presumably, taste, you didn’t buy them. As art — creativity, quality, legitimacy — their reputations are abysmal. Perhaps this is because Jennifer Lopez and Celine Dion have perfumes but Cate Blanchett and Helen Mirren do not. That reason may be that Lopez has a strongly self-associating demographic eager to monetize her celebrity, whereas Mirren focuses on acting. It may also be that much of celebrity perfumery is unadulterated garbage.”

There is a legitimacy to Burr’s claim that the face of the celebrity scent mattered - were their fan base going to turn into a consumer base that would be interested in buying a lower budget and lower cost perfume? The biggest perfume dynasties tapped into a market that loves both popstars and affordable beauty products: young women. And the celebrity scent would soon evolve to cater to this audience alone.

The original celebrity perfumes — the White Diamonds, the Glows — smelled like white flowers and coconut, lime and lilacs. The celebrity perfumes that came after smelled like a five year old’s birthday cake. What happened?

They were visited by an Angel.

PART TWO — WHERE ANGELS FEAR TO TREAD

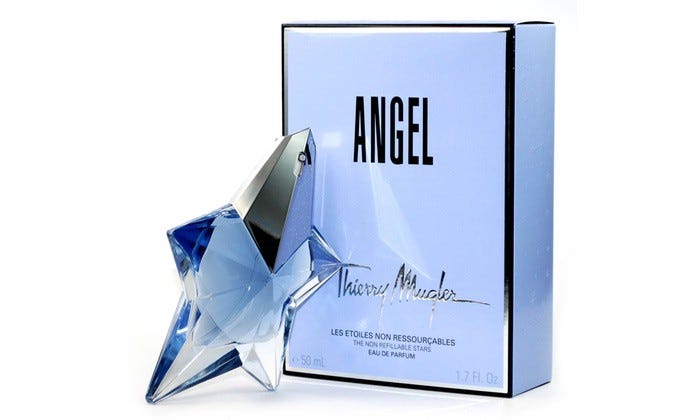

Angel killed the celebrity perfume.

If we’re ringing up charges, Angel (Thierry Mugler, 1992) has a lot to answer for. Angel, which if you have smelled even once I am sure you have never forgotten, is based around an ethyl maltol-patchouli accord that is meant to evoke the smell of chocolate. This it does to relative success - a true chocolate note in perfumery is virtually impossible (the crucial element of cocoa butter is always missing, leaving the whole thing smelling like the cacao nibs they sell in health food stores) but Angel smells like cocoa and it smells sweet, tricking your brain into thinking ah, chocolate. The rest of Angel is a blackcurrant opening and a neon floral in the mid, all of it so strong that it has a sillage wider than the meteor that killed the dinosaurs.

Angel is the newest of the benchmark perfumes, the Shalimars (Guerlain, 1925) and Chypres (Coty, 1917) that define their genres and are the reference point for all others. Technically a subset of the amber-oriental fragrance family, Angel’s central fruit-floral-sugar-patchouli structure was so novel it created its own category called gourmands. The purpose of a gourmand is to make you smell like cake. The cake may have different toppings — praline, marshmallow, berries — but it is, at the end of the day, a cake.

The majority of perfumes that Angel has inspired seemed to think that there was not enough sugar in the original of the species. Before Angel, feminine targeted perfumes were not overly sweet. Post Angel, gourmand perfumes centered on ethyl maltol and patchouli have saturated the market. We call this current crisis in perfumery the fruitchouli.

As time passed and we all grew accustomed to sweet perfumes these scents have further reduced the natural facets of patchouli in the Angel accord while the sugar note has only gotten louder (Flowerbomb, Viktor and Rolf) and louder (Roses Vanille, Mancera) and louder (La Vie est Belle, Lancome). The result is a cloyingly sweet fruit—floral-vanilla perfume with a kind of muzzled patchouli in the base trying valiantly to give some sense of balance while standing on one leg with a hand tied behind its back.

The arrival of the gourmand and the explosion of celebrity perfumes were two fires that were inevitably going to combine into one super inferno. The chocolate ‘trick’ of Angel is created primarily by an inexpensive synthetic (ethyl maltol) and an inexpensive natural (patchouli) or a synthetic patchouli derivative. To create a skeletal Angel requires no thought, no talent, and no money. It therefore comes as no surprise that celebrity perfumes flocked to Angel like vultures on a carcass.

In Fantasy (Britney Spears, 2005) the ethyl maltol accord in the listed notes is called white chocolate. In Circus (Britney Spears, 2011), it is violet candy. In Hidden Fantasy (Britney Spears, 2008), is Napolitano cake. In Private Show (Britney Spears, 2016), it is whipped cream and dulce de leche. In Festive Fantasy (Britney Spears, 2020) all false identities have been shed and it is simply called sugar.

Gone were the White Diamond years, when a perfume might be dripping with white flowers; gone even was Glow, which may have been inexpensive but still brought more to the table than an achingly sweet vanilla that irradiated the air around you three feet in any direction. The defining characteristic of the celebrity perfume would now forever be sugar.

The target demographic for the fruitchouli (young women) and the demographic for celebrity perfumes (young women) overlapped a third, equally important demographic: people who could usually not afford to spend $100 or more on a perfume. Thus celebrity perfume became the newest form of a species that has existed since mass market perfumery began: the good natured, democratically priced everywoman scent. And with it came the stigma that has always followed a cheap perfume made for women: that the woman who wears it is cheap as well.

PART THREE — A BEAUTIFUL DARK TWISTED FANTASY

Sexism killed the celebrity perfume.

Gender in perfume marketing has become a hot topic in recent years. A part of a wider cultural discussion about gender, the rise of the unisex perfume and its appeal to millennials - those same teens who bought celebrity perfume in droves in the 2000s - is probably the most widely discussed phenomenon in perfume in the past decade.

But where gender in perfume intersects with class is something that no one wants to talk about.

For masculine branded perfumes, there are a lot of affordable options — perfumes kept outside the glass cabinet. But there are little to no male celebrity perfume brands . Antonio Banderas and David Beckham are popular, but there aren’t any multi million dollar empires like Britney Spears or Sarah Jessica Parker. This is because there is no need for it on the market: for nearly a century cheap masculine perfumes have included some of the best masculines ever made.

To buy a masterpiece in the masculine branded category will never cost you more than $50. Brut, Old Spice, Pino Silvestre, Pour un Homme de Caron, Aramis, Encre Noire — you would be hard to find better masculines than any of them at thrice the price. Cool Water (Davidoff, 1988), Pierre Bourdon’s masterpiece that has singlehandedly defined the masculine market since it was released, will cost you about $20 neat. Until Aventus (Creed, 2010) opened the floodgates for masculine scents at exorbitant prices, buying perfume as a man was a budget affair.

This is connected to men’s perfume descending from aftershave splashes, which were watered down and cheap citrus-cologne scents used at barbershops. Women’s perfume, in contrast, was corseted for a long time by the fact that women weren’t meant to buy it. The husband of yore spent $10 on his own scent four times a year and splashed it wildly, then spent $100 on an eau de parfum for his wife on their anniversary. Women didn’t buy perfume. You smelled how your husband wanted you to smell. Such was scent for seventy years.

Because of this price disparity built into the gender divide, traditional ingredients in men’s perfumes - lavender, citrus, oakmoss - were cheap to produce, and ingredients in women’s perfumes - iris, rose, jasmine - were much more expensive. Even as we enter a time when natural ingredients are highly regulated and synthetics replace them, a cheap formula in a floral-feminine perfume is not going to smell as natural or as luxurious as a cheap masculine.

Chandler Burr sums up the mentality:. ‘If you had money and, presumably, taste, you didn’t buy (celebrity). As art — creativity, quality, legitimacy — their reputations are abysmal.’

As I walk past the celebrity perfume shelves I think where are the budget gems marketed to women, the Pinos and the Aramis? The kind of thing perfume fanatics call a dumb reach — something pleasant and inoffensive that you don’t have to think about before you spray it all over?

It is completely possible to make a feminine branded celebrity perfume that genuinely smells good. They are rare but findable in the wild; M (Mariah Carey, 2007) which smells like grape soda and gardenia; Queen (Queen Latifah, 2009) which takes the Angel structure and makes it woodier, not sweeter; Fame (Lady Gaga, 2012) in a delightfully creepy bottle, which smells like flower petals dripping in honey in a room filled with smoke.

When we consider that the same perfumers that make designer and niche perfumes make celebrity perfumes, and that synthetics are more prevalent that natural ingredients, there is no reason why the feminine ‘cheapie’ should have a stigma attached to it.

We love to decry celebrity perfume, but we all secretly want them to be good. There’s nothing as beloved as a hidden gem, a great ‘cheapie’. We all have them in our collections — it’s just that not you’re not meant to admit that you’re wearing it. An article in the New York Times highlighted this phenomenon:

“To experiment with celebrity fragrances is “modern,” said Felicia Milewicz, the beauty director of Glamour, who routinely mixes hers with more rarefied essences, a practice she likens to wearing, say, a $14.99 Zara shirt with a $900 Dolce & Gabbana skirt. “It is a stylishly audacious form of rule breaking,” she said, “and the mark of great confidence.””

The celebrity fragrance is only acceptable if you acknowledge it cannot and should not be worn alone; it is only acceptable if you pair it with a luxury product. If you do not own a $200 perfume to layer with Curious (Britney Spears, 2004) or Fancy (Jessica Simpson, 2008), that’s when it becomes embarrassing.

It is about who gets to smell expensive. If you can smell good at $25 for 100ml, why would anyone buy 100ml at Dior or Chanel for $200?

I confess to you: I don’t want to smell like a cupcake. But sometimes when I walk past the celebrity scents in the chemist, I kind of wish I did. The woman who wears Fantasy is the woman who gets drunk after two Smirnoff Blacks: she’s happy and she paid a lot less than you to get there.

The celebrity perfume, marketed to women and universally considered embarrassing to wear, was already on the path to destruction. Then came social media.

PART FOUR —THE KARDASHIANS COMETH

Instagram killed the celebrity perfume.

Back in the ancient times of 2001 Britney Spears caused controversy for being seen in public drinking Coca-Cola when she had just signed a deal with Pepsi. This became a scandal mainly because people were horrified to discover that celebrities, beyond their sponsorship deals and public appearances, were real human beings. This was a time before Instagram, before the livestream: celebrities still had a mystery about them. Unless they were on an episode of MTV Cribz, you didn’t know what their house looked like.

The celebrity perfume was marketed on the idea that you are buying it to smell like the celebrity. It connected you in some way — a parasocial relationship before social media. For some reason it did not matter that no celebrity was ever going to wear a perfume with their own name on it. It did not matter that everyone, on some level, knew this.

This is perhaps best displayed by the case of Rihanna. She is part of what we’ll call the L’Inderdit effect: internet sleuths discovered that she personally wears Love By Kilian (By Killian, 2012, also known as Don’t be Shy). I have never seen a reviewer or commentator mention this fragrance or their interest in it without mentioning Rihanna. And yet her own line of perfumes, including Reb’l Fleur (2010) and Rebelle (2012), continued to release new flankers well into 2018. They ended only when Rihanna launched her own beauty line with LVMH, Fenty Beauty.

Reb’l Fleur, Rihanna’s first fragrance, is perhaps one of the better failed Angels. It is a heavy patchouli-cacao powder bomb, with a cherry top note and a coconut mid that reminds me of the chocolate bar Cherry Ripe. It is strong and sugary, but there are other notes combating the ethyl maltol that keep it interesting on the skin of an hour or two.

Love, Don’t be Shy is also a sweet fragrance, but is based instead on orange blossom and a resinous, traditional amber base of vanilla and labdanum. It smells expensive because your nose can pick up the complexity of the natural ingredients. It does not smell anything like Reb’l Fleur, or any of the perfumes in the Rihanna line.

All the celebrity perfume brands were promoting Pepsi and drinking Coke now. When asked why she had not released a celebrity perfume Adele said in an interview, “I wouldn’t wear my own perfume. That’s not me being in touch with my fans. I’ll always wear the same perfume I’ve always worn since I was 15, Christian Dior Hypnotic Posion.”

Why were people buying these perfumes if the illusion had been shattered? What is the appeal of a celebrity perfume if you aren’t buying it for the celebrity? There was none. Twitter and Instagram flourished, the era of the social media celebrity began, the veil lifted and celebrity perfume sales plummeted severely.

Celebrity perfume died because celebrity went viral. The only perfume empires that survived were the ones whose celebrities were too big to fail (Beyonce, Rihanna, Britney Spears) and the perfume lines that hadn’t been simple Angel clones (Elizabeth Taylor, Sarah Jessica Parker, Jennifer Lopez), mainly because the celebrity faces had actually been involved in the creative process.

By 2014, the celebrity perfume was in steady decline. Their moment had passed, wedged between the launch of White Diamonds in the 90’s and the explosion of the internet in the late 2000’s. The celebrity perfume’s inbuilt advertising had become the celebrity perfume’s curse: there was no smokescreen now that celebrities were documenting their lives online. A perfume couldn’t be sold on the mirage that the celebrity was wearing it.

The celebrity perfume could have faded into obscurity, a relic of the 2000s like hiptops or Britney and Justin in double denim. But, like an old sitcom that comes to Netflix and has a surprise revival, the celebrity perfume wasn’t dead just yet. It was dragged into the Instagram era by none other than the social media celebrity, Kimberly Kardashian.

In charting the history of Kim Kardashian’s adventures in fragrance we witness not only the evolution of celebrity from the 2000s to the 2010s but the way in which the culture of perfume itself has changed. Her first perfume, Kim Kardashian (Kim Kardashian, 2009), was in a round bottle with a flat lid reminiscent of the apothecary style flacons of Chanel. It is a tuberose and citrus scent exactly like Michael (Michael Kors, 2000). It was created by Claude Dir, a perfumer for the fragrance house Givaudan who created Curious (Britney Spears, 2003), Heat (Beyonce, 2010), and Simply Chic (Celine Dion, 2010).

Kim Kardashian would release a few more scents in this traditional celebrity perfume style until she abruptly scuppered the company and rebranded into KKW Fragrances, a company controlled by her and not a larger conglomerate. This was celebrity fragrance 2.0, as Kardashian took pains to demonstrate:

"I think that with the social media aspect of it, being able to really reach so many people, I think it's going to work. Obviously I'm in the celebrity category, but I just wanted a bottle that was so simple that can look like it's something sitting on your counter and be a beautiful object. I tried to make it really timeless so that it can't just all be about a celebrity fragrance. It's the first time that a fragrance is really being sold with the model that I'm doing it at. It's really just using online sales and doing it all digitally.”

And Kardashian knows her audience. Unlike the rhinestone-and-glitter bottles of celebrity fragrances in the past, KKW perfumes are in bottles shaped like emojis and crystals, cartoon hearts and sculpted bodies. They are announced on Instagram and often feature collaborations with other members of the Kardashian clan.

Perhaps the most infuriating thing about the Kardashian perfumes is that they are good. Not masterpieces by any means, but not thoughtless Angel zombies either. If we take Elizabeth Taylor as celebrity perfume’s genesis and the avalanche of the 2000s as its second wave, then the Kardashians are at the forefront of the third wave of celebrity perfumery. Instead of dying like everyone expected, the species had evolved for social media and realised that what the perfume smells like does, indeed, matter.

As they rely less and less on the celebrity and more on the scent and the bottle to sell units, the Kardashian model has become the new baseline for celebrity perfumery. And what do Kardashian perfumes smell like? They smell like other perfumes. More expensive perfumes. There is not a single scent in the Kardashian lineup that isn’t a dupe of a mass market designer or niche scent. The era of the perfumed dupe had arrived.

PART FIVE — DUPED!

Science killed the celebrity perfume.

A dupe is a beauty industry term for a lower cost product that attempts to duplicate a higher end product. Dupes have always been contentious ground in perfumery, where formulas are kept secret but are often imitated or outright plagiarised. This is possible through the use of the gas chromatograph. As Chandler Burr explains:

“The problem was that in 1952 A. T. James and J. P. Martin developed a machine called the gas chromatograph. This was an ingenious device that separates individual molecules on an invisible conveyor belt of gas and IDs each of them as they float by. It tells you what molecules are in the material before you, unlocks the juice, and hands you a printout like a grocery store cash register spitting out a paper listing of the items sitting inside your plastic bags at the checkout. (A little more complicated, but still.) And from that instant, secrecy began a slide to uselessness.” ²

Natural perfumery ingredients contain many molecules within them, mostly in trace amounts. Synthetic ingredients contain one molecule. Putting a perfume that has natural ingredients into a chromatograph will give you an incredibly long list of every molecule in every natural ingredient. Putting an entirely synthetic perfume in a chromatograph will give you a list of 10-30 synthetic molecules.

When I began writing about celebrity perfumes I made a mental list of the best of the best, the celebrity scents worth a sniff for anyone: Truth or Dare (Madonna, 2008), Lovely (Sarah Jessica Parker, 2003), Cloud (Ariana Grande, 2018). And I realised two things: the first was that none of them were gourmands.

The second was that they were all dupes.

Lovely (Sarah Jessica, 2003) is legendary: it is the only celebrity fragrance to have a book written about it. Well, half a book: it is the subject of The Perfect Scent by Chandler Burr, which contrasts the creation of Lovely with the creation of Un Jardin sur le Nil (Hermès, 2003). What the book fails to mention is that Lovely smells nearly identical to For Her (Narciso Rodriguez, 2003).

For Her uses white musks — the scent in your fabric softener —to create a perfume which doesn’t smell dirty or animalic but still smells personal because it is the smell of your clothes, things warmed by your body. For Her is a chypre that has light white florals in the mid and patchouli instead of oakmoss in the base to give a depth and character to the musk. Lovely is all of that, just with a lower formula cost. It is slightly less artful, more floral in the opening and less smooth in the drydown. But it’s still a well made perfume, novel for a celebrity scent as it keeps your interest.

Truth or Dare (Madonna, 2003) pulls a similar trick. It is nothing more and nothing less than a low cost Fracas (Robert Piguet, 1948), perfumer Germaine Cellier’s showstopper tuberose that was famously Madonna’s favourite scent. It is rumored that Piguet considered suing Madonna for how closely Truth or Dare resembled Fracas — and chose not to when their own sales soared.

The great stumbling block of these celebrity dupes was that the formula cost simply could not stretch to photorealistic copies of the original scents’ natural ingredients. Duping a perfume with even a few natural ingredients is difficult, but not impossible. Duping a synthetic perfume is dead easy. What celebrity perfumes needed was a high end perfume that was entirely synthetic, something they could accurately dupe and sell by the truckload.

What they needed was Baccarat Rouge 540.

Baccarat Rouge 540 (Maison Francis Kurkdjian, 2015) is a perfume that contains, according to creator Francis Kurkdjian, “only synthetic molecules. I put in orange and tagetes and a few naturals right at the very end, but otherwise it’s synthetic. There’s a synthetic oakmoss, veltol and Ambroxan and hedione.”

Baccarat Rouge 540 costs $350 for 100ml.

What does this mean for the humble celebrity perfume? It means get me a bottle of Baccarat and put it in the chromatograph immediately. The most dupeable scent in the world is something everyone already loves and nearly nobody can afford. There are too many Baccarat Rouge dupes to name, but the best of them is Cloud (Ariana Grande, 2018).

Ariana Grande’s perfume portfolio is managed by Designer Parfums, a conglomerate who began adding perfume brands (including Jennifer Lopez) to their portfolio in 2009. And in an admirable display of adaptability in a fragrance market that is hostile to celebrity perfume, they are showing how the game is played. Ariana Grande uses the lessons learned from the Kardashian model - Instragrammable bottles, the scents all dupes for higher end perfumes - and applies them to a traditional, Elizabeth Taylor structure - low formula cost and low buying price, sold in chemists and wherever teenage girls gather.

The scents are made by fragrance firm Firmenich and they are all clever, wearable dupes. Cloud is their crowning glory, a simulacrum of Baccarat Rouge so convincing it makes you smile in wonder every time you smell it.

I have a bottle of Cloud. When I spray it and close my eyes, it smells damn good. It smells strange, slightly sweet and slightly medicinal, like saffron from another planet, the way flowers might smell if they were growing through radioactive earth. It smells like Baccarat Rouge 540, for $44.99. It smells like synthetic oakmoss, veltol and Ambroxan and hedione.

Should the consumer feel guilty about these synthetic celebrity dupes, the old shaming about an affordable scent in a new bottle?

There are many niche brands who sell perfumes that are entirely synthetic and proudly advertise this. Sometimes these perfumes claim to only contain one synthetic molecule. Not A Perfume: Superdose (Juliette Has A Gun, 2018) will cost you $220 for 100ml. It claims to contain only cetalox, a Firmenich synthetic that is meant to replicate the scent of ambergris. If you are not anosmic to cetalox (which a portion of the population is), the molecule smells like an unholy chimera of musk, fake wood, and cheap amber. It is one of the most ghastly scents in perfumery today. If we are generous and allow that Superdose has a dilution of 25 grams of pure cetalox, you can buy the same amount from perfume supply stores online for $30.

Covet (Sarah Jessica Parker, 2007) predated the current trend of lavender notes in feminine perfumes (Mon Guerlain, Libre, R.E.M) by a decade and still smells slightly strange and daring. It blends an aromatic fougere opening of lavender and citrus with a lily of the valley heart and a restrained patchouli-chocolate base, the florals balancing the sweetness and stopping the scent from tipping into cupcake territory. There is a clever balance between what is traditionally masculine and feminine in perfumery in Covet. It is an entire perfume, from top to bottom. It costs $20 for 100ml.

There will always be a market for high end perfumes with natural ingredients and a price that reflects the formula cost. But we are in a time when it is possible to create something like Baccarat Rouge 540 using only synthetics. Celebrity perfumes are indeed cynical monetization strategies - but one could argue that niche and designer perfumes from Chanel downwards are as well. And these perfumes are all being made by the same perfumers.

Celebrity perfume died because the business model was flawed from the start, because they became synonymous with cheap gourmands, because Instagram culture spurned them, because high end niche brands came in and stole their target demographic. All of this is true. And yet the celebrity perfume, the democratically priced everywoman scent, has endured despite all odds.

PART SIX — HERE YOU COME AGAIN

Dolly Parton is going to save the celebrity perfume.

The country singer, vaccine funder and Tennessee theme park founder released her first perfume, Dolly, in 2021.

The listed notes for Dolly are pear, blackcurrant, mandarin orange, peony, jasmine, vanilla orchid, lily-of-the-valley, amber, musk, tonka, sandalwood, fir, and patchouli.

When I saw that Dolly Parton was releasing a celebrity fragrance in 2021, in a bottle that looks like it could have been made for a perfume released in the genre’s heyday in 2005, I felt a strange sense of completion for the celebrity perfume. Perhaps Dolly Parton is the perfect celebrity to embody all the virtues of the genre: a celebrity who has been famous since Elizabeth Taylor’s White Diamonds, a singer like Britney with a dedicated fanbase to push sales, selling a perfume with a note list that looks on paper like a rudimentary Angel with a low formula cost and a low buying price. A Dolly Parton perfume would naturally be accessible, humble, and entirely lacking in snobbery. She is perhaps one of the only celebrities left for whom there is enough love and consumer trust to actually sell a perfume.

Perhaps amidst the snobbery and the cynicism there is some redemption to be had.

Among the small group of celebrity scents worth your time is Stash (Sarah Jessica Parker, 2016). Smelling Stash is an odd sensation. Even with my eyes closed I know it is a celebrity fragrance; there is something in the synthetics, perhaps the woody molecule, that smells like a lower price point than the ones in designer scents. Along with the woody base there is a furl of olibanum that comes and goes in Stash, not smoky but a bit scrubby, the way frankincense tears smell before they are burned. But most of all Stash makes me think of a quote from perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena:

Among the spicy scents there are ‘hot’ spices (such as cinnamon, cloves and hot pepper) and ‘cold’ spices (cardamom, nutmeg and black pepper).

I think about this quote often, because to my nose there is absolutely a distinction between hot and cold spices. And Stash is a study on cold spices, perhaps one of the better ones I’ve smelled in perfume at any price point. The entire thing is structured on a cardamom-pistachio-milk accord, with that woody amber synthetic grounding it in the base. But it is not overly sweet; the milky note instead makes the whole thing feel creamy. Stash is like a Middle Eastern dessert that uses aromatics and depth of flavour to counter and balance sweetness. A slice of halva and a glass of milk; that’s Stash.

I love Stash. I love its cold spices and its apothecary bottle; I love how it is a genuinely interesting and intelligent perfume. It is a celebrity perfume that fragrance addicts — even male ones — will concede is a hidden gem. It is also the fragrance that a woman claims made a kangaroo attack her. Purchase at your discretion.

There are more outliers like Stash in celebrity perfumery, you just have to hunt for them. Henry Rose is Michelle Pfeiffer’s new fragrance brand, touted as a revamp of the celebrity for ‘the wellness era’; Gwenyth Paltrow did something similar with the perfume arm of her wellness superbrand, Goop. There’s Richard E Grant’s brand, Jack Perfume, and the new wave of Youtuber perfumes. These perfumes are priced like designer or niche houses in an attempt to shake off the stigma of the traditional lower priced celebrity scent.

Then we have the strange case of Elizabeth and James, a celebrity perfume brand that does not use its celebrities as advertisement. When I posted about the brand a few months ago on twitter, people were shocked to learn that it was owned by Mary Kate and Ashley Olsen. The bottles are tasteful, even elegant — they look like marquee lights at a Broadway show. The scents? Not too shabby. None of them have note pyramids that are too long, as if the Olsens or their perfumers understood that a few simple accords done well would suffice.

Nirvana White (Elizabeth and James, 2013) is a respectable white floral with a clean laundry musk in the base, similar to Lovely. Nirvana Black (Elizabeth and James, 2013) is a little more daring — marketed as unisex, it attempts to find a halfway point between violet and sandalwood through a vanilla bridge whilst not veering into gourmand territory and almost succeeds; the drydown gets too sweet for it to totally escape the confectioner’s trap but the journey there is pleasantly woody and well rounded.

Nirvana Rose (Elizabeth and James, 2016) is a stunner. A feminine marketed floral, it uses geranium and vetiver, notes typically used in masculine scents, to ground the rose and take it into dark, sultry, even frightful territory. Vetiver is a grass grown in Haiti and its roots are harvested for their oil, which can have citrus facets but also a delightfully dark and smoky scent that bring to mind mulchy, wet dirt. Geranium’s scent is quite similar to a fresh green rose with minty facets that add brightness in small doses and medicinal sharpness in large ones. Both of these ingredients lend their darker, more challenging sides to Nirvana Rose and make it as interesting to smell as the most lauded niche scents.

There is too much potential for money in the celebrity perfume for it to ever truly die. “Perfume is the single best tool for monetizing celebrity that’s ever been created in the history of the world,” Chandler Burr said in an interview for NPR. “It is a kind of financial alchemy the likes of which we’ve never seen.” ³

There will always be a market for cheap and cheerful perfumes - why should they not also be masterpieces? The fragrance industry has the capability of making them with synthetics alone. The fact that fragrance brands gatekeep by price is not an indication of the buyer’s taste but the industry’s obtuseness.

I don’t believe in the concept of guilty pleasures. If it’s not hurting anyone, I don’t believe in feeling bad about something that brings you joy. And though it can often feel tied up in our identity, reflective of who we are and who we want to be, perfume is something that is purely for pleasure. We wear perfume because we want to smell good, because we want to feel good. Perfume is, as Sali Hughes puts it, ‘the most egalitarian beauty product… you don’t have to be young, thin, beautiful, or mega rich to smell like a million dollars’. ⁴

In 2018 New Yorker Mindy Yang opened a store named Perfumariē, where customers would blind smell a number of perfumes and choose their favourite. The scents ranged from rare, vintage, and expensive to budget, drugstore, and celebrity. One of the most popular scents in the store was Pitbull Man (Pitbull, 2013).

Yang says that “if customers fall in love with one of the fragrances they try, the store will connect members to perfumers so they can buy a bottle. Or you can simply come into the store and fill a large apothecary bottle with a scent on tap. That way, no one has to know that you keep Pitbull Man on your vanity.”

The message is clear: buy celebrity perfume, own it, love it — but be ashamed about it. Don’t post it on your instagram. Don’t put it on your vanity. Your favourite perfume may be Midnight Fantasy, but for god’s sake don’t tell anyone.

“Snobbery has no place in the world of perfumery,’ Luca Turin told the New York Times. ‘The idea is to pay attention to the smell, rather than the hype.”

My bottle of Ariana Grande Cloud is 100ml, the larger size, even though I usually try to get the smallest bottle possible when buying perfume. I got the bigger size because it was a great price — $44.99, free shipping. It sits in my perfume tray next to a bottle of Ormonde Woman (Ormonde Jayne, 2008) that costs $240 for 50ml. I spray the Ariana Grande with abandon and hoard Ormonde Woman like it is as precious as gold. I love both of these perfumes. But Cloud is, by far, the perfume I get the most compliments on in my entire collection.

I was once hailed at the checkout of a grocery store by a woman who told me that her daughter (who was standing behind her, blushing furiously) absolutely loved my perfume, and kept smelling it as I had walked around the store, and could I tell them what it was? Feeling honour bound to explain the whole thing, I told them it was Cloud, which was a dupe of Baccarat Rouge 540. As I got to the Maison Francis Kurkdjian bit I saw I was losing them, and so circled back and firmly said, ‘Ariana Grande. Cloud.’

I told them it was on special at the discount chemist. $44.99. You can spray it all you like before you buy it. They don’t keep it behind the glass. ◙

REFERENCES

All prices mentioned are current to the Australian dollar as at 15 April, 2021.

¹ Page 14, “Perfumes The Guide 2018.” Turin, Luca; Sanchez, Tania (2018)

² Page 87, “The Perfect Scent: A Year Inside the Perfume Industry in Paris and New York.” Burr, Chandler (2008)

³ Chandler Burr was not immune to the celebrity scent bug - he collaborated with niche house Etat Libre d’Orange to create the scent You or Someone Like You. He also claims to have introduced Tilda Swinton to the owner of Etat Libre d’Orange, with whom she collaborated on the perfume Like This.

⁴ Sali Hughes may not thank me for including her here — she does not believe any cheap perfume is good. But this sentiment is important to me, and she describes it best.

For more of my writing about perfume, subscribe to this substack or read my (very) deep dive into the house of Chanel and their newest perfume, Le Lion.

FURTHER READING

Orders Evaporate for Celebrity Perfumes

Whiff of Despair: What’s Behind the Decline of Celebrity-Branded Fragrances

The death of celebrity perfume: Why no one wants to smell like an A-lister anymore

The Guilty Pleasure of Smelling Like Vanilla and Peach

How Britney Spears Built a Billion-Dollar Business Without Selling a Single Record

Celebrity Fragrances: Why Stars Do Them, And How Much They Really Make

Celebrities, Best-Selling Fragrances, Sales Figures & The Perfume Industry

Modern life smells so good it’s killing the cheap perfume industry

Extremely well written, well researched, thoughtful, organised, so many things learned and insights gleaned. The passion for fragrance, history and cultural sociology all shine through brilliantly. Thank you so much for your amazing article!

this was so good—incredibly comprehensive and well-written!!