Sede vacante. The seat is empty.

It is the open wound at the heart of the world's largest religion. The throne of St Peter, the Holy See, the seat that holds the keys of the kingdom of heaven, the rock upon which. The religion in question is Catholicism, which is a subset of Christianity and yet still the faith of over a billion people. This seat, and Catholicism, is the oldest continuing office of power on Earth.

It’s hard to escape the cultural reach of the Catholic Church when you live in the Western world. It is, for better or worse, one of the load bearing walls of our civilization. Its influence wafts from the church into the streets of civic life, the courts, the schools, the arts.

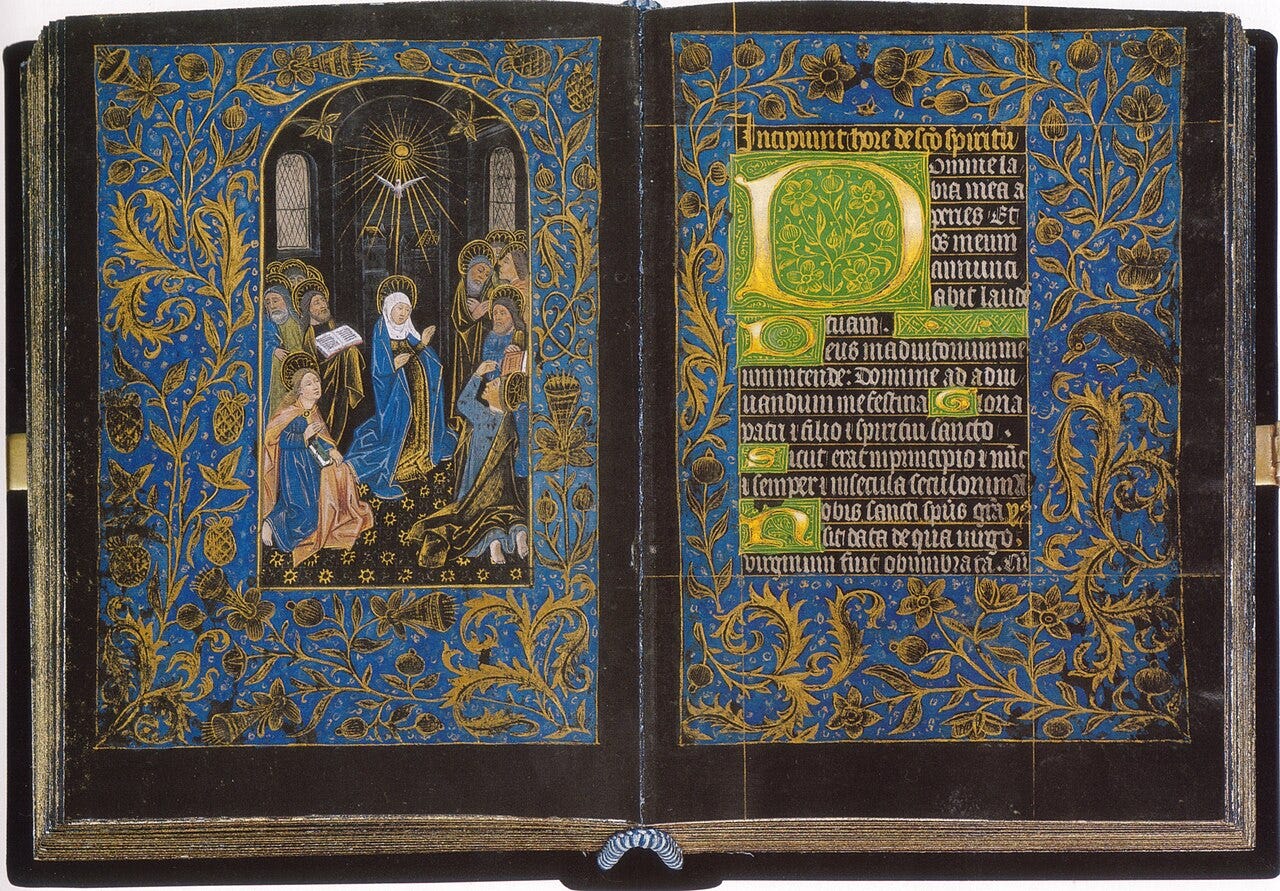

The concern of all religions is the soul, and Catholicism will walk any path it can, use any ammunition it can find, to reach yours. This includes art and song and verse and food and community and power and fear and love - and scent.

Religion, like perfume, is performative, and there is no religion that is better at performing faith than Catholicism. There’s a pageantry to the church of Saint Peter in which scent plays a prominent part. If you have ever walked into a church you’ve smelled it. Even when you leave it clings to you. The scent of God, the smoke from the thurible, the holy resin - the incense.

The Bible, amongst other notable uses, is a perfume lover’s dream. Its stories and passages are filled with powerful imagery of fragrance, the scent of bodies and empires and revelations. The Book of Exodus contains a passage where God, like an evaluator at Givaudan, gives Moses a briefing to blend the sacred incense to be burned in temples:

“Take unto yourself sweet spices, stacte, and onycha, and galbanum; these sweet spices with pure frankincense: of each shall there be a like weight: And you shall make it a perfume.”

Humanity does not agree on much. But it seems we can all agree that if there is a scent that is closest to heaven, it would be incense.

Technically any resin or material that is burned over coals or in ritual can be called incense, but our focus today is on the traditional interpretation of frankincense. Also known as olibanum, this material is a resin from the boswellia tree that grows natively in Eastern Africa and Southern Arabia. It has been associated with the spiritual for thousands of years, long before it was gifted to Mary by one of the wise men.

In the world of modern perfumery, frankincense is an ancient material that still has a modern resonance. There are houses and perfumers that obsess over incense like our ancestors did, trying to build monuments around its resinous, piney dryness. There are countless scents that use incense as a central note to give depth and mystery, to evoke the spiritual or the divine.

The power of incense is the same in perfume as it is in religion: it fills the air around you, the smoke filling every corner of a room or a chapel. It gets in your nose and lingers for hours in your hair. It is dry and sharp but also sweet somehow, mellow, as if it holds some kind of ancient wisdom or deep knowledge. There’s always a feeling of wafting upwards when you smell incense - as if your perfume, like a thurible, is a vehicle for sending your thoughts directly to whatever lives above.

We can’t talk about every incense perfume in the world today. But the Pope is dead, the seat is vacant, and the walls of the Vatican are layered in smoke from thuribles that have swung incense over the tomb of St Peter for hundreds of years. So let’s talk about a few great ones.

Incense Extrême

Year: 2008 / House: Tauer / Perfumer: Andy Tauer

In my collection of natural and raw perfumery materials I have a container of frankincense tears. These are small, precious sand-and-cream coloured pebbles the size of pine nuts. They are hard and roll pleasantly in your hand, like tiny misshapen jewels. Their smell has always reminded me of the top floor of a library I visited when I was very young - the smell of dusty old things tempered with an odd sweetness that is almost vanillic on the back of your palate. I think this is because paper, like incense, is a byproduct of trees, and it is that woodiness that threads them together.

Raw incense smells like old books, which is one of the best scents in the world.

The natural scent profile of incense is difficult because it defies easy categorization. This is also what makes it so wonderful - it is good for things to contradict themselves. Frankincense is woody and dry like cedar, sharp and harsh like lemon, sweet and yet also smoky all at once. It’s one of those materials, like vetiver and rose, that is a perfume entirely to itself. This poses an interesting decision for the modern perfumer: use the right amount of incense and it will give a perfume depth, body, and complexity - use too much and you will confuse the nose and give the wearer a headache.

In the world of incense perfumes the soliflore (the solicense?) that seeks to reconstruct the scent profile of the natural material have exploded in popularity since the groundbreaking Avignon (Comme des Garcons, 2002). As an incense obsessive, I hunt down these perfumes like a greedy man seeking treasure. But the only one I have ever smelled that does justice to that raw, complicated smell of frankincense is Incense Extreme.

If you don’t want to buy raw incense but you want to understand what the full profile of this note can be in perfumery, Incense Extreme is the perfume I would send your way. You would probably not thank me for this. Though I have grown over many years to love it, when I first smelled this perfume I stood up and walked away. Absolutely not, I thought. Too spiky, too heady, too dry, too much.

But the perfumes you really love are often the ones you don’t understand at first. When I had smelled more, understood more - when I was wiser - I returned to Incense Extreme and found myself appreciating it in all its rough beauty. It’s now a scent I crave every so often - when I get the itch there is nothing else that will do.

Incense is a common theme in all of Andy Tauer’s perfumes, but Extreme is the one that brings this fascination to its final form. The first spray (and spray small) uses the bitterness of coriander and petitgrain to enhance the dryness of its central incense note. Tauer uses c02 extraction for his incense notes, which is why I think they smell so realistic and so damn good.

And it is photo realistic, this incense. I can almost feel the texture of the tears in my hand when I smell it - so woody and sharp and resinous all at once. It is dry, so dry you almost feel parched on the roof of your mouth. It’s the same kind of dry that lives in the scent of pencil shavings and gum leaves and dusty old books. This kind of overt woodiness from a frankincense note is very rare in perfumery. Incense perfumes are usually dreamy, wispy things, translucent and detached. The arboreal punch of Incense Extreme is as far from a smoky, ethereal incense as the earth is from heaven.

In many ways this is the type of incense you’d find lingering in a hippy shop, the kind that sells tarot cards and hanging beads and little coloured stones for luck. It is grounded by Tauer’s signature woody-ambergris base - the Tauerade - which you either love or you hate. For me it gives all of his scents a chewy, resinous glow, an ochre radiance like sunshine gleaming through Baltic amber.

Incense Extreme is a pointed effort to make an incense perfume that is unliturgical, and in that it succeeds. But there’s something about it, in all its harsh beauty, that evokes the Old Testament anyway. It smells like the church before it was a church, the rough bones of a force that will move mountains.

Unfiltered, terrifying, and beautiful - that is Incense Extreme. It’s an Old Testament incense. The old God feels closer than the distant God of the later books. In the Old Testament, God speaks and God judges. This is a scent for Esther, for Samson, for Job - a scent of a god who would command you sacrifice your son, and at the very last moment would swap him for a ram.

Rien Intense Incense

Year: 2014 / House: Etat Libre d’Orange / Perfumer: Antoine Lie

If you weren’t raised in Catholicism (and sometimes even when you were) there is no way of understanding it as a religion. It is complicated, convoluted, and thick with history in the way all great and ancient religions are. It’s not the oldest religion still around but it is the biggest, and that’s because Catholicism understands the power of imagery. Cathedrals, saints, relics, stained glass windows - Catholicism is dramatic and opulent.

A skeptical mind (potentially but not exclusively from 16th century Saxony) might question how the opulence of the Church can be reconciled with a central figure that preached poverty, charity, and humility. The answer is that in the about 320AD the Emperor Constantine brought Christianity into the center of the Roman Empire, and a few decades later the Emperor Theodosius made it the state religion. Christianity became a part of Rome, and Rome became a part of Christianity.

Constantine gifted the sitting pope the Lateran Palace, which became the seat of the papacy for a thousand years until the Avignon exile. It is the Lateran Basilica, and not St Peter’s, that is still the diocese of the Pope today. And it is the Pope, of course, who is the Bishop of Rome - or should we say that whoever is the Bishop of Rome inherits the primacy of Saint Peter.

Popular history says that the Fall of the Western Roman Empire happened in about 480AD. But the state religion never fell. It’s still there. The church survived Rome because the church consumed Rome. The language of the church, the Nicene Creed, the Curia, the Pontifex Maximus - these are the hallmarks of the Catholic Church but they are the legacies of Constantine, not Christ.

A spare and ascetic incense can match those parts of the church that are mendicant. But opulence calls to opulence, and for the red-cloaked inheritors of Rome there is Rien Intense Incense.

Like the Roman Empire that barely withstood Attila, Etat Libre d’Orange is brand that now seems to look sadly back on its former greatness. They made waves in 2006 with the enormous Rien from Antoine Lie, and followed it up in 2014 with the Intense Incense flanker. Both perfumes are gigantic leather-aldehyde monstrosities, the kind of perfumes that smell like the creator was throwing everything they could find into the juice and hoping something would stick.

One assumes that’s the joke of the name - it’s called nothing and smells like it contains everything - and it’s a tribute to Lie’s brilliance that these perfumes not only work but scrape quite close to brilliance.

Huge, bombastic incense perfumes are the trademark style of Amouage, and though Rien Intense Incense is too edgy and threaded with obviously synthetic notes there is something reminiscent of the Amouage house style here. Lie adores a black pepper note (see his Scorpio Rising from Eris), which immediately deflates the spirit as it conjures the opening of many tired designer masculines. But he always seems to pull it off somehow, blending the pepper into the rest of the scent to make an odd, postmodern sort of harmony.

Frankincense is not a naturally airy material, but its association with smoke is strong in the collective cultural memory. Thus an airiness can be implied in perfumery by using other light materials, as Lie does here with aldehydes. The fizzy-soapy champagne pop of this note lifts the opening salvo of this scent before it descends into a roaring lion’s den of leather and animalics.

Incense is a powerhouse in perfume because it can weave through these notes and find commonalities with all. Its piney dryness sparks off the aldehydes and bergamot and pepper; its smokiness enriches the thick floral rose heart; it swirls to form part of the the scents lingering leather-amber drydown. There’s so much going on here that it is like a feast after a triumph - so much indulgence you can make yourself sick with it.

There’s something about all this intensity that makes you feel a little uneasy. I think that the unease - your nose not knowing which note to seek out, which part to focus on - is part of the point. In this way the scent interacts with the survival mode that is linked to scent in our brains. You have to solve the issue of what the smell is, because it could be something dangerous - something that wounds.

In this way, too, it is reminiscent of the Church. In this way it smells like Rome’s legacy most of all.

Les Liturgies Des Heures

Year: 2011 / House: Jovoy / Perfumer: Jacques Flori

There's a solemnity you can only find in an empty church. No matter how small it is a church always seems to have so much space, such empty air - the gable roof, the stained windows, the cold floor. A space for light, and birds, and angels.

Somehow, in every church, there is always a burning candle.

It is one of the strange miracles of perfume that scents can sometimes smell warm or cold. An amber that is rich in labdanum and patchouli and benzoin always smells warm and intimate, like it is designed to be sprayed on your biggest winter coat. In a similar fashion incense, when pared back to its translucent heart, can often smell cold and remote.

It seems counter-intuitive that something that we burn to release its fragrance can smell cold, but it is nonetheless true. Frankincense is almost clinical in its coldness, medicinal, as if it has been swung in a thurible over cold Sunday morning stone so often that a bit of the church floor has infected the resin.

When incense perfumes are minimal and cold they are at their most inhuman, and therefore their most godly. If you’re the type who likes to smell like a cold church that time forgot you are in luck: there’s plenty of these perfumes going. I am one of these people and I own a good handful of the usual suspects: Cardinal (Heeley, 2006), Full Incense (Montale, 2009), Bois D’Encens (Armani, 2004), and always Avignon.

But in this sub sub category of perfume there is something special about Les Liturgies Des Heures.

If the three perfumes in this article form a trinity, then Les Liturgies would be the holy ghost. There is something ethereally haunting about it, like the icon of a saint that died before their time.

Les Liturgies is a scent from Jovoy, who are a perfume stockist who began creating their own line and have developed a bit of a cult following for their troubles. This is because Jovoy make perfumes for the obsessive, and they understand that the obsessive is interested in very specific things. The obsessive wants a patchouli that does, in fact, smell of a 1960’s music festival; a leather that does smell like the jacket of that dangerous bikerider of your dreams; and an incense that smells like the sunset vespers of the monastery in The Name of the Rose.

Les Liturgies doesn’t have a typical three act perfume structure of head, heart, and base. It starts as it means to go on and is nothing but incense from top to bottom. Like incense, the perfume has a turpenic lemon-pine facet that blends into a sweet myrrh and olibanum amber. Though myrrh is a resin also used as incense its scent is noticeably different from frankincense, but the two blend well together to create a deeply contemplative resinous affect here. There is something about Les Liturgies that almost has a waxiness like a blown-out candle similar to the fatty aldehyde effect of Man 2 (Comme des Garcons, 2004).

There is, unavoidably, a touch of mildew about it all. Incense perfumes can be like that sometimes - Les Liturgies is reminiscent of Messe de Minuit (Etro, 1994) in that both smell like the room in the church attic where the incense is kept when it’s not in active use. For the right person there is beauty in this, something gothic that conveys a sense of unending time. For the wrong person, it smells like a damp basement that lacks a window.

Les Liturgies is incense perfumery at its most meditative. It is a cool, quiet perfume that has very little projection, designed to be worn and pondered over by you alone. Most incense soliflores are similarly faint skin scents that need to reapplied if you’re planning to wear them for an entire day. The scent is ephemeral; the memory lingers.

When I spray an incense perfume it is a scent that triggers my imagination and sends my mind reeling back into the past. Incense is a scent that holds so much history that it almost transcends religion to become a smell, like smoke and ashes, that has been grooved into the brains of humanity as a species.

When I smell incense I wonder what the ancients thought when they burned it, thousands of years ago. Why did it smell so precious to them in the past? Why does it smell so special to us now?

The great religions of the world sprung up in times when science and philosophy were still nascent, and the answers to all of life’s mysteries ended in one god or another. Humanity is older now, though perhaps not wiser, and when I roll my frankincense tears in my head I feel grateful that I don’t understand everything, and there are still parts of the world where there are some mysteries left to uncover. ▣

Incense is at the core of perfumery, rooted in its original latin root of "per fumum" through smoke. It’s fascinating how incense bridges ancient rituals with modern fragrance, connecting us through time and scent!

Many of what is mentioned as frankincense and myrrh patchouly, coriander, Amber, sandalwood, black pepper, Bergamont, and such are some of the ingredients used in the original formation of Yve Saint Laurent’s original opium perfume. They have changed their formation of ingredients which does not smell the same as the original opium created in 1970’s as a woodsy, sensual smoky scent. I wish I could find that scent that I crave so much again . Do you have any suggestions or recommendations. I loved reading your article of incense perfumes . Thank you .

Kpk