The Five Fragrances series is inspired by the Five Books project, seeking to do something similar with perfume by providing five exemplary fragrances on any given theme.

PROLOGUE

There is nothing on earth like the brutality of an Australian summer. Heat bears down like a mercurial god has the sun in his fist and is squeezing; sometimes you will wake in the morning already covered in sweat. This is the heart of bushfire season, when the sun melts snow-themed Christmas decorations and air conditioning bills skyrocket. The very land gets so parched that it is sapped of all colour like a picture in sepia - anything meant to be green turns a dull brown that blankets the countryside. In December on the far side of the world, it is bone dry.

If you live in Australia then you know that dry has a smell. It’s not the smell of the desert; that is more the smell of dust, the grit of sand, the scent of a place where nothing can grow. Dry is when you’re in a place that can be lush, but simply isn’t. Dry is when the vegetation surrounding you is withered and crackling like it is begging for the wind to bring in a wildfire and put it out of its misery.

Dry smells like vetiver.

What is vetiver?

Vetiver grass, chrysopogon zizanioides, is also known as vetivert and vettiveru. it originated in India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. It has long been a part of the culture in these countries, where vetiver roots are woven into blinds to keep homes cool in the hot season. Wild vetiver oil (ruh khus) is highly prized for the calming and cooling effect its aroma gives. It has also been used as an insect repellent much like patchouli, that other great plant of perfumery. Khus is even used as a flavouring agent for food, water, and flavoured cordials.

Vetiver’s use in fine French perfumery began when the French took vetiver and planted it in many of their former colonies, notably Haiti and Bourbon (now the islands of Réunion). Haiti is now the world’s foremost exporter of vetiver oil; over half of the worldwide vetiver yield comes from the Haitien region of Les Cayes.

After rose and jasmine, vetiver is perhaps the most used natural in perfumery. This is because of its versatility, its benefits as a fixative to enhance other notes and make them last longer, and because vetiver has no adequate synthetic replacement. Small amounts of vetiver are found in countless perfumes but as a dominant note it is traditionally considered a masculine scent. Vetiver is a wonderful fixative but it has a tipping point: an overdose of vetiver will dominate everything else in the composition.

What does vetiver smell like?

At first, vetiver smells like fruit so sour it makes your eyes water. This is the hesperidic facet of vetiver, which has much in common with the citrussy tang of grapefruit.

Next comes the grass. If you have ever sat in a field during a physical education class and started picking at the grass and shredding it between your fingers, you know the green aspect of vetiver. It is a little bit sharp but still earthy, even dirty, with some of the mineral tang from the soil. Add to that grassiness is a rooty aspect, earthy and dusty like the smell of a burlap sack filled with potatoes.

Rounding out vetiver’s scent profile is a touch of inky smoke. This is not the sweetly thick smell of things burning but more stale, slightly sour, like the air in a room after someone has smoked an entire cigarette and then extinguished it.

If you like the acidic tang that fills the air when you crush a rind of grapefruit peel, the smell of dry grass, the ink from a calligrapher’s pen, or the smell of a bathroom after someone has just showered and the soapy steam is lingering in the air, then vetiver is for you.

Vetiver is unique in the perfumer’s palette: it has the depth and the range of a woody note without a woody facet, and this is what makes it so distinct and so powerful. Perfumers may enhance or erase any of vetiver’s attributes, like raising and lowering pitch: the sulphuric element that has much in common with the scent of grapefruit is often used to ground citrus perfumes; the dirty, earthy element can balance out richer and sweeter notes; and the pitch-black smoky element, which is my favourite of all, can make anything smell darker and more sinister. When perfumers are bold enough to stretch the boundaries of vetiver as a material, true greatness can be found.

These are five scents that I believe show the remarkable complexity and versatility of vetiver in perfume.

ENCRE NOIRE (LALIQUE, 2006, Perfumer: Nathalie Lorson)

There is a wonderful word from Ancient Greek, chthonic, that means ‘in or beneath the earth’. The Greeks used it to refer to both the subterranean and the Underworld as both were terrifying: both meant death. In this is perhaps the rudimentary concept of the Christian hell, but in Greek there is more emphasis on the on the actual earth, on being beneath the soil, of things in the dirt. Hades, ruler of the Underworld, is the lord of gold and metal and gems, that which is unearthed - anything found under the ground is his domain.

Encre Noire, in all its glory, is a chthonic perfume.

Imagine a room in a grand old house, filled with knickknacks and furniture that has been gathering dust. Then imagine someone getting rid of everything that is spare or unnecessary, taking the entire space down to the bare bones as if peeling back layers until only the handsome structure of the room remains. This is what Encre Noire (French for ‘black ink’) does to the perfumer’s vetiver, and it is a remarkable thing.

If you have never smelled vetiver before I would send you in the direction of Encre Noire, then watch gleefully as you sprayed it and your face is either transformed utterly in joy or in horror. This perfume does not use vetiver as a base or fixative, and it doesn’t attempt to recreate the depth and complexity of natural vetiver root. Instead the miraculous Nathalie Lorson puts all the smoky and bitter and bracing facets of vetiver in the spotlight, using a heaping dose of Iso-E Super (a synthetic that smells similar to pencil shavings) and cypress to hollow some cheeks onto the skull. It is a stark and beautiful perfume, and aptly named - there is something of the bitter tang of black ink in this scent, something almost metallic.

What is about vetiver, so cleverly emphasised in Encre Noire, that makes us think of the earth? It is similar to the strangely pleasant earthiness of beetroots - you know you are not eating soil but somehow beets give the feeling of dirt anyway, of an earth rich in minerals. Vetiver has this same lovely dirtiness. For many it is a nostalgic smell - you never seem to spend as much time in the dirt as you do when you’re a child. There is something reassuring about smelling of the earth.

Encre Noire does not sit heavily on the skin as it is composed of vetiver, cedar, and cypress, with no heavy or rich base notes turn it darker or deeper or sweeter or more palatable. But nor is it the kind of light-hearted and transient thing you would expect of a citrus-fresh cologne or fougere. Encre Noire is perfumery in monochrome, a black and white rendering of vetiver that is merciless and all the more beautiful for being so.

This perfume is a true cult phenomenon, and for good reason - it is a masterpiece in a stunning bottle that can be found for less than $50AUD for 100ml. It is so popular that is has spawned several flankers, but they all add other notes - furniture to the old room - and something of its spare, stark beauty is lost. I spray it often and in heaping doses - either it does not last on my skin or I quickly become hyposmic to the iso-e, but I savour every moment that this black ink vetiver masterpiece lingers on my skin.

When we think of the world chthonic we think of silt and clay and loamy soil. It is easy to forget that beneath the earth is where gold is found, where bones become coal and graphite turns to diamonds. Encre Noire is a stark perfume, utterly without joy or warmth or anything humane. There is no citrus, no grapefruit, nothing even of the humid rootiness of vetiver absolute. Encre Noire eschews all: it is cold, inhuman, and aloof. And yet there is something so beautiful about its harshness, like brutalist architecture on a city skyline, like the way ink pools in water and looks so similar to smoke. Otherworldly and dark as the abyss: Encre Noire is chthonic in every way.

SYCOMORE (CHANEL, 2008, Perfumer: Jacques Polge and Christopher Sheldrake)

When Christopher Sheldrake makes perfume, he sets out to conquer worlds. In Sycomore, he attempts to summit the mountain and create a vetiver to exceed all vetivers. He succeeds.

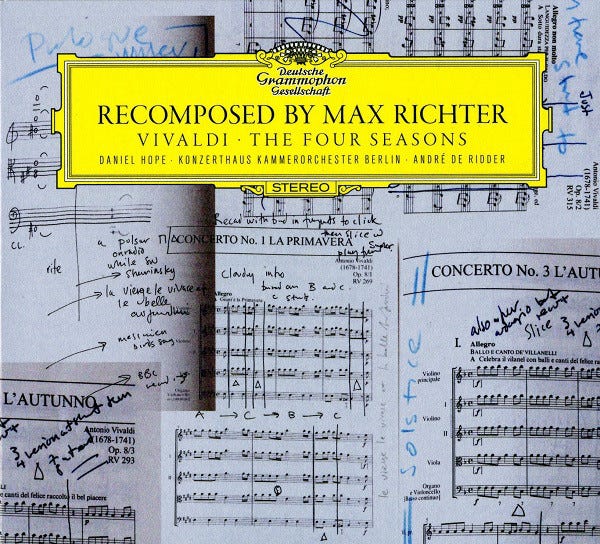

If you are a fan of Vivaldi then you know that there are days when his work is simply too overwhelming, as beautiful and complex as it is. But on those days there is The Four Seasons Recomposed by Max Richter, a stunning album of postmodernist classical beauty. This album takes Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and puts it under the carving knife, removing everything that can possibly be taken away before the entire ship of Theseus collapses. Richter then simplifies what remains, often looping and repeating a certain melody or violin solo, using the old bones to create something familiar but also foreign, something new.

Of his album Richter has stated, ‘My piece doesn't erase the Vivaldi original. It's a conversation from a viewpoint. I think this is (a) way to engage with it." This is the precise spirit in which Sycomore engages with vetiver. Sheldrake, like Richter, has honoured natural vetiver in the finest way he knows by picking the clearest melody in the tune and creating something minimalist, sophisticated, and utterly beautiful all around it.

It is hard to put preconceived notions aside when smelling perfume. I am often caught up in my ideas on what a perfume should smell like, and though I sought out Sycomore because I heard it was an all star vetiver I expected to dislike it because the Chanel style is not for me. But when I finally got my nose across Sycomore, it all faded away. I spray all new perfumes on a blotter first (this saves you the agony of spraying something on your skin that you truly cannot bear), and almost automatically turned back and sprayed it on my wrist as well. The power of vetiver was so great that it took twenty years of my Chanel ambivalence and ground it into dust.

The defining characteristic of Chanel perfumery is abstraction - their scents never smell of solidly defined notes, a rose or a jasmine, but rather a diffused and well blended chorus of notes that blends into a new and unique whole. The vetiver in Sycomore is given this similar treatment, buffed and blended until it becomes part of a larger and more complex whole, but the strong bones of this note sit close to the skin. Sycomore is undeniably a vetiver perfume - a vetiver in its finest clothes.

There is much in common between Sycomore and Encre Noire. Encre Noire preceded Sycomore, and if you spray them side by side it seems like Encre Noire is a half formed thought and Sycomore is the polished, perfected finish: the vetiver heart of both perfumes is almost exactly the same. Sycomore adds skin to the skeleton, fleshing out an earthy and stark vetiver with a lush accord that smells, as is typical for Chanel, of abstract elegance. There are some spices, a touch of powdery tobacco, some aldehydes - all rendered with restraint and elegance. Sycomore is a more humane perfume than Encre Noire, but it is still strangely lifeless.

But where the typical lack of spirit in Chanel perfumes changes for me in Sycomore is that the vetiver at the heart of this scent longs to bloom on the skin. It a perfume that is ingeniously incomplete because the final element needed is for you to wear it. Chanel perfumes are designed to be aspirational - to make you smell like the person you want to be - but Sycomore does the exact opposite. It grounds you in place, smelling so intricate and lovely that you become more aware of everything around you, that famously soothing element of vetiver taken to a place where it is no longer merely nature but now poetic, now the finest art.

It is as if Sycomore is saying, See what beauty can be found if we take these parts of vetiver and carve it back, round the edges, give it the finest sheen? And perhaps the most remarkable thing of all is that it does not feel derivative: you can feel that this creation comes from a place of love. Sheldrake loves vetiver and Richter loves Vivaldi, and you can feel it; there are parts of Four Seasons Recomposed and parts of Sycomore that make your heart ache to experience them.

A vetiver sun allowed to shine with the finest of constellations all around it: Sycomore is perhaps the best vetiver perfume on the market today. And for Christopher Sheldrake, another world conquered.

LAMPBLACK (FZOTIC, 2013, Perfumer: Bruno Fazzolari)

Some perfumers seek to answer the question that is central to all art: what is beauty? There are many ways to approach this: one is to make the beautiful even more beautiful, to make a tuberose that is the sum of all tuberose perfumes. Another way is imitation: to try and recreate the exact smell of a time, a place, a natural. And then there is a more subversive way, which is to take smells that are commonplace in our lived and to turn them into perfume and say, this can be beautiful too. And so it is with Lampblack.

One of the best smelling places on earth is a garage. The sweet-oily scent of petrol, the cold mineral bite of metal, and the acrid smokiness of very hot things: this is the enticing scent of industry. In perfumery, recreating this is not untested ground: the burning rubber of Dior’s Fahrenheit and the slightly grubby motor oil slick of Comme des Garcons’ Black are just two of many perfumes that harness the smell of oil and steel. Lampblack is another, but it comes at this genre so adroitly that the first time I sprayed it my brows furrowed together in confusion, and then raised in astonishment. Perfumer Bruno Fazzolari has created what I like to call a burning petrol perfume using… grapefruit?

To make a citrus fragrance may be the easiest brief in perfumery, as citrus smells wonderful without any alteration. But it is a genre that traces back hundreds of years, and everything that could possibly be done with citrus has been done a hundredfold - to make an innovative citrus fragrance may be the hardest brief in perfumery. And this is what makes Lampblack so remarkable - there are a hundred vetiver and grapefruit scents. There are none that smell like this.

The commonality between vetiver and grapefruit is a slightly sulphuric scent that is described as hesperidic. If you have ever stuck your thumbnail into an orange peel and been gifted with a spray of essential oil in return, this is a hesperidic scent: an eye-watering and bracing acidity with an almost floor cleaner harshness. Vetiver is paired with grapefruit to give lift and freshness to a scent but can often become too harsh, like the way your eyes squint and water if you eat something too tart. There are many grapefruit/vetiver scents in the world and I liked exactly none of them until Lampblack threw something in to mediate: the note of nagarmotha.

Much like vetiver, nagarmotha (also known as cypriol) is a fast growing grass originating from the Indian subcontinent. Unlike vetiver, nagarmotha is a weed that is considered one of the most invasive plants on the planet, and essentially spread itself throughout the entire subtropics despite humanity’s best efforts to stop it. Its scent profile sits at a wonderful crossroads between woody-earthy, cinnamon-spice, church incense, and cold metal.

What nagarmotha brings to Lampblack is the smell of ink. (The perfume itself is named after a type of soot used in the creation of India ink). But what is the smell of ink, exactly? It is a metallic with a touch of sweetness, that smell of steelwork or machinery that always seems somehow cold. There is also something wet about this inky vetiver smell in Lampblack - it never smells of words dried on the page but rather of ink when it has just been spilled, held in that liquid state. And despite all of these metallic, harsh connotations, Lampblack still somehow smells of the earth.

If Encre Noire is sparse and spare and pitch black, Lampblack would be gunmetal grey. The grapefruit-nagarmotha accord is bracing; it smells like the office of a calligrapher who works above a factory where they smelt iron. And underneath all of this, digging deeper and deeper, is the vetiver. It lifts the brightness of the grapefruit and deepens the darkness of the cypriol and even makes the mineral smell of the metal stronger. Vetiver rounds out this perfume by rooting it in the earth and enhancing that deliciously foreboding feeling that Lampblack gives, exciting but alarming, like the way electricity thickens the air before a lightning storm.

This perfume is so remarkably self assured that you have to admire its arrogance. Bruno Fazzolari knows this smells good and his confidence shines through to the drydown. And thus we come to the paradox at the heart of it all: Lampblack is beautiful. Lampblack smells like motor oil. Is Lampblack trying to be subversive, or was it us who were wrong the whole time, dismissing these practical smells of the garage and the factory as anything less than sublime?

Lampblack reminds me of the work of Robert Therrien, who took common household items like dining room furniture or dishes and made supersized sculptures out of them, as if daring you to claim that these functional things could not be art. Perhaps purpose is what makes art, and thus beauty: art deserves your attention because someone decided to make it, because someone took this commonplace thing and elevated into beauty. And in wearing a perfume you are giving it purpose - you are saying this smells good, this smells how I want to smell, I present myself to the world smelling like this. It brings purpose into the equation for what is typically a group of very practical smells. You work in the garage to work - the smell is secondary. But you wear Lampblack because you want to wear it - the smell is primate.

Lampblack is a fine example of what independent perfumery brings to the realm of fragrance. This is not a perfume that would have made it through the gauntlet of the major houses unless it was for a truly left of field brief, and it is too accepting of its own strangeness to be niche. This is true artisanship, both in its quality and its weirdness. The great Achilles heel of Lampblack is its prohibitive cost (nearly $200AUD for 30ml) - but this, too, is a question of art. Is the beauty of this fragrance worth the price to you?

Lampblack is a perfume that is unquestionably beautiful. It is beautiful because it is so well made and because its cleverness is so clear and undeniable. Like good architecture, it takes the functional and lifts it into something that is more than the sum of its parts.

HWYL (AESOP, 2014, Perfumer: Barnabé Fillion)

There are two kinds of time travel in perfumery: vintage scents that serve as an epitaph for their time and modern scents so evocative that to smell them feels as if you have been flung back in time. Hwyl is the second kind.

One of the most striking images in the 1993 film The Piano is the titular instrument sitting on a cold beach on the south island of New Zealand. It is surrounded by water, and forest, and mountains, a dark figure on the white sand. The image is clear: it does not belong. It is unnatural on the landscape, thrown onto the shore and stuck there - the forest is too dense and the mountain too steep to move the piano uphill to where the owner lives.

The piano, like its owner and the man she has arrived to marry, are European foreigners on Maori land. The landscape itself is harsh and unforgiving, heaping misfortune on the settlers and their attempts to tame it. But The Piano is not only about the violence of nature: like all films about colonisation it is about the violence of one person imposing their will on another. The violence of colonialism, of forcing a will and authority onto a group of people who did not ask for it and do not want it, is perhaps the worst kind of violence because it is dishonest - it pretends it is progress. The piano on the beach is stark and beautiful. But it is important to remember that it never belonged there in the first place.

Vetiver, much like patchouli, first arrived in Europe as an insect repellent. Vetiver roots were layered between bolts of fabric to protect them and the cloth would absorb the scent over the months long journey from the east. Vetiver has always smelled, to the Frenchman, of a long journey.

Colonialism, violence, nature and fate: these are the kinds of topics that haunt the mind when you are wearing Hwyl. It is an utterly morose perfume, sober and contemplative. It is constructed around three main tenets: a harsh and humid vetiver; a full and smoky frankincense; and what is perhaps the dustiest thyme note in perfumery today.

Dust is a contentious word in perfume. For many people it means the smell of something powdery, but the two are quite different. Hwyl does not smell like powder but it does smell like a room where the dust has settled and gone stale. All three of its main notes combine to smell of an old abandoned place where the dust lingers to remind you that once people lived there and once it had purpose. That strange feeling that comes over you in the afternoon when your mind wanders and a beam of sunlight comes in, illuminating all the spools of dust in the air that you hadn’t realised were swirling all around you - that is the way that Hwyl diffuses on your skin.

Much of this feeling comes from the thyme. If you have ever cooked with thyme then you know that it tastes the way a dusty attic smells and smells how a mothball would taste. It adds depth and complexity in small doses but makes you feel like you are in the middle of hay fever season in large quantities. Unlike other herbs in perfumery, which can bring lift or bitterness, the thyme in Hwyl smells like a plume of dust descending on you, catching on your clothes and sticking in the back of your throat. The immediacy of this on first spray makes you feel as if you have been plunged back in time.

Adding to this sensation is the frankincense. Incense is a chameleon in perfumery, much like vetiver - it can be full and rich or sparse and smoky, lemony and sharp or soft and heady. Humanity has used incense as perfume for thousands of years and smelling it always feels like a ritual, spiritual in some ancient way. It is the somberness of Japanese incense, which smells woody more than smoky, that is furling in Hwyl.

Hwyl is starting to sketch its self portrait, an olfactory snapshot of a forest: trees so tall they block out the sun, wind whistling between the trunks, moss thick and damp on the forest floor. This is a fairytale forest in the sense that it is a place where bad things can, and do, happen.

But at the end of it all, Hwyl is a vetiver perfume. Hwyl’s vetiver is humid, thick, rooty, and coarse. The vetiver here makes everything smell more: the thyme is dustier, the incense is woodier, the scent lasts longer, pushes further, feels bleaker. But most importantly of all, it makes the whole affair smell natural.

The great trick of Aesop perfumes is that they smell like they are made entirely of essential oils. There is a sleight-of-hand known only to Barnabé Fillion that is bottled in Hwyl, a sense that he simply stumbled upon this smell on a forest floor somewhere and was clever enough to bottle it. All perfumes that truly smell natural churn your stomach for a moment - there is nothing that screams unnatural more than a combination of notes meant to smell sweet, saccharine, and pleasant. Hwyl instead smells natural because it is humid, rooty, and packed with dirt.

Hwyl does not have a stereotypical perfume ‘structure’ and is quite linear. It’s all there on first spray, boldly planting its feet in the ground and demanding you either embrace it or get out of the way. Hwyl smells like nature fighting back.

This perfume is oppressive, claustrophobic, evocative, and bordering on melancholy - why on earth would anyone wear Hwyl? I own a bottle of this perfume, and I bought it because the most terrible thing of all about Hwyl is that it is so very beautiful. Like the hand that slaps your cheek and then soothes the blow, it is bracing and at the same time intimate. It is stifling and oppressive, a perfume that surrounds you and feels like it is turning the world sepia and covering it in dust. The humid dirtiness of the vetiver and the powdered, chalky feeling of thyme combine to give this scent almost a texture, a sense that it sticks in the back of your throat and haunts you from top notes to drydown. Wearing Hwyl feels as if you are stuck in someone else’s memory.

Do the echoes of colonialism ever truly fade? To smell a vetiver perfume indicates that they will not any time soon. It is a natural like so many in French perfumery that is intricately tied to empire, exploitation, and the unequal relationship between the first and third worlds. Colonialism is the backdrop of our society - it may get softer through the years but is ever present, like a tune you can never quite get out of your head. When I wear Hwyl this tune is brought to the forefront of my mind. If music is voice without speech, then perhaps perfume is music without sound - and if it is, then Hwyl is a symphony.

VETIVER VERITAS (HEELEY, 2014, Perfumer: James Heeley)

Imagine the scent of clean.

When people talk about the scent of clean, they are almost always talking about feminine or unisex marketed perfumes. This is because there is no need to make this distinction in masculine perfumery - smelling clean simply is the entire genre. Walk down the toiletries aisle at the supermarket and seek out all the male branded products - they are easy to find, big hulking bottles in black or red or bleu - and look at how they’re scented: to evoke the sea or a crisp winter’s day or something to do with minerals and all of it clean, clean, clean.

A clean perfume seeks to prolong the fresh-out-of-the-shower scent of water and soap and citrus. There is something in the lizard brain of a man that makes him want to smell like a bar of soap, and most will rarely stray from this style of perfume. Thus the masculine perfume market is much more conservative than the feminine, and though there’s been great change in recent years, true innovation remains rare.

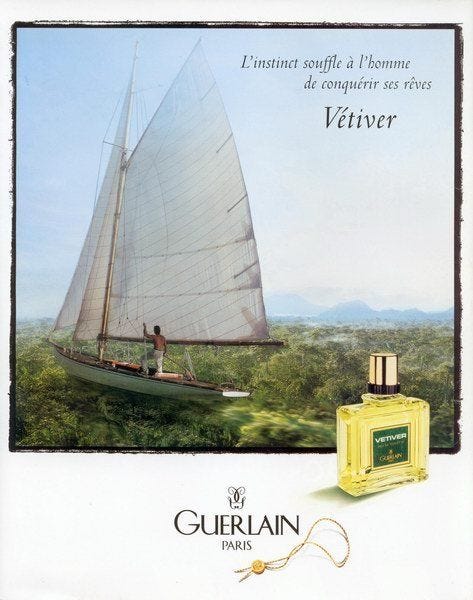

One of the great turning points in masculine perfumery came when Guerlain quietly but surely set the gold standard for every vetiver scent ever made with their Vetiver (1959). This is a scent that does for its genre what Cool Water (Davidoff, 1988) did for the aquatic-fougere, which is to say it is so beautiful and deceptively linear that no one can improve on it, and all similar perfumes must settle on mere imitation. Guerlain’s Vetiver is the perfume Jean-Claude Ellena keeps trying to make (Terre d'Hermes, Vetiver Tonka) but can never quite capture. I do not love this perfume, and I don’t wear it, but I do admire it. If you want to understand vetiver and its place in perfumery, you must smell it.

When the perfume lover thinks of vetiver, it is Guerlain’s benchmark that the mind immediately jumps to. But this perfume, as iconic as it is, is not a true vetiver - it is a clean vetiver. It is both clean in that it smells soapy and fresh and clean in that the vetiver itself has been scrubbed of all its darker, dirtier, and more challenging facets. There is a reason this perfume structure was as popular in 1961 as it is in 2021: it is timeless because perfumes houses keep making it, again and again, and they keep making it because it sells, and it sells because men want to smell clean.

When the fresh and hesperidic facets of vetiver are given center stage, the result is the scent of a man who is handsome but doesn’t care about it: a young Harrison Ford. Vetiver Veritas, a remarkable all natural perfume from the house of Heeley, takes this man and returns to him a bit of the chest hair, a drop of Hemingway gruffness. It is half fresh, light, and handsome citrus-vetiver, and half sack of dirt. This is what the polite perfume fan will call a challenging perfume, and what the average Youtube commenter would call a god damn pile of dirt.

Vetiver Veritas also happens to be exactly what is says on the tin: this perfume, above all others, is a true vetiver.

In Vetiver Veritas you get a playful sense of the perfumer playing mad scientist: throw in as much vetiver as you dare, add a touch of grapefruit and lavender and a sprig of mint, then stand well back to watch what happens. The fact the perfume smells so good is a testament to the natural beauty of vetiver absolute.

Upon first spray, one is in fact suspicious that perfumer James Heeley has simply diluted some vetiver oil in a bottle (the scent is marketed as all natural, after all). Every one of the harshest and most confronting parts of the note come tumbling out: the sulphuric bite, the inky bitterness, and the overwhelming smell of dirt that good vetiver gives you all roar at the top of their voices for a good twenty minutes. Grit your teeth and bear it.

After the furore of the top notes fade, you are left with a blotter that makes you wonder: is there such a thing as clean dirt? There is something in the dirtiness of vetiver that smells like the greenest grass, thick with chlorophyll, like something so alive. This may be the most prized aspect of vetiver, as all of perfumery is the art of making dead things seem alive again. Natural perfumery ingredients must die to become useable; they transform; they transcend; they become both greater and lesser than what they were when they were living.

Vetiver grows tall above ground but its roots grow even longer underneath the soil; it is both above and below just as it smells both clean and dirty, of life and of death. Do the two halves contradict? Very well, they contradict. Vetiver can bear it. Vetiver contains multitudes.

This clean dirt smell is why vetiver is almost exclusively marketed as a masculine scent. This, of course, is nonsense - I am a woman and clearly adore vetiver - which speaks more to what advertisers believe men want to smell like than anything else. Gender associations in perfume are cultural biases, and when we smell the soapy aspect of vetiver our mind links it to the aromatic-fougere clean man scent that is familiar to most from their fathers or their brothers. But I have never known a man who wears vetiver, and when I wear it I do not feel masculine, or fresh, or clean. When I spray Vetiver Veritas I think of how people weave vetiver root into blinds to cool their homes on the subcontinent, how tradition says that vetiver needs water to bloom and grow fragrant. Vetiver Veritas is a cool scent more than a clean scent.

Truth is not something you would be wise to look for in perfumery. Even perfumes that smell note true are facsimiles, olfactory Frankensteins cobbled together to try and create something that will never smell the same as a real natural. But if you compare Vetiver Veritas to other vetiver perfumes, it is certainly truer - unapologetic about all of the difficult elements of the note, even embracing them, saying vetiver smells like dirt and this perfume smells like dirt and you are going to wear it because you want to smell like vetiver and vetiver smells like dirt. There is a bravery in this that you cannot find in other vetiver scents on the market, even Frederic Malle’s elegant Vétiver Extraordinaire or Tom Ford’s buttery-rich Grey Vetiver. Nobody is going to dress Vetiver Veritas up or try to soften it; take him as he stands.

Vetiver Veritas will only project in a small radiant arc around you, hugging close to the skin. It is not a loud, forceful, and overbearing ambroxan cologne like so many masculine scents in vogue today. In an industry where synthetics reign supreme and authenticity is constantly sought, Vetiver Veritas is a fine example of a true natural perfume, in all its coarse beauty. You want parfum naturel? Breathe in the beautiful dirt - and be careful what you wish for.

EPILOGUE

A bottle of vetiver perfume travels a long way to reach you.

Vetiver arrived in Haiti in the 1930's, brought by two French agronomists. It is not a plant native to the Caribbean, but in Haiti it found the ideal humid conditions in which to thrive. Many natural ingredients in perfumery are tied to place in order to make them seem exotic and tantalising - Bourbon vanilla, Calabrian bergamot, Bulgarian rose - and Haitian vetiver is one of them. But this advertising does not accurately convey how important the vetiver crop is to Haiti. The island nation accounts for over 60% of the world’s vetiver oil yield, and vetiver makes up a significant portion of Haiti’s entire export portfolio.

By the time that vetiver arrived, Haiti had been an independent country for nearly a hundred and fifty years. Haiti was the first country that ever overthrew a colonial power. But the presence of vetiver in the country, and the facts of its harvesting, is one of those ripples of colonialism that continues to permeate our modern world.

Vetiver is fast growing and takes only a year to yield its oil, making it a 'cash crop’ for farmers. As one Haitien farmer surmises:

“Vetiver gave me everything I have: house, school for my kids, food for my family. As long as I’m alive, I’ll work in vetiver fields. It’s what saves us… Death is the only thing that will separate us from vetiver.”

Digging up and extracting vetiver is hard work, and the roots need dry, tough soil conditions to thrive. But an article on the ‘super crop’ points out that all of the workers in the vetiver fields that they spoke to said they had never seen or smelled vetiver oil. “It’s sent across the sea … They make oil from it, and it smells good. But they get it from us for close to nothing.”

Perfume is accessible in the sense that you can leave your house and find a bottle to purchase within a mile or two. But it is inaccessible in that most of us have no frame of reference for natural perfumery ingredients unless you live in an area where they are cultivated. Thus we come at scent in reverse: our understanding of labdanum and galbanum and myrrh is entirely from complex compositions - perfumes - where they are distorted and blended, making the actual scent profile difficult to discern.

I seek to correct this imbalance. I buy little jars of absolutes, vials of tinctures, frankincense tears and lavender leaves. I don't want to make perfume, only understand it - and to understand the natural ingredients themselves, these things that have grown around us and become a part of the culture and story of humanity.

I bought a little jar of vetiver oil years ago, Haitian and of good quality (or so the company claimed). Sometimes I do a little experiment: I close my eyes, curl off the lid, inhale, try to ignore every fact about vetiver running through my mind, and just focus on how the scent feels. It's a hard task, trying to smell without thought. What you are really doing is trying to switch off a hundred thousand years of evolution and go back to the primal self, the one who couldn't form words but could smell danger.

I come from a hot, dry place where the summer is long and the sun is unforgiving. Vegetation here is not lush - the rich and full scents of things blooming is quite foreign to me. I don’t like the smell of newly grown things; I like my nature a little bit dead. The indolic florals, the parched grass, the rolled up hay - these are some of my favourite scents in nature and in perfume. So maybe it was fated that I would love vetiver, that this strange and complicated scent would speak to me. A grass with deep roots, this dead scent that somehow makes you think of living things - the magic trick of all perfumery writ large in a tiny vial of vettiverru.

The natural complexity of vetiver will never be truly captured in a fragrance. I see this as a reason not to love perfume less but to seek out nature more - smell genuine vetiver root and your understanding of vetiver perfumes, and of nature, and maybe even of yourself, will expand.

I close my eyes and breathe in. It’s all there in the vial: the smell of fresh dirt and grapefruit and black ink, ruh khus in India and the vetivert roots on the hills of Les Cayes. It is a cliché to say that a natural ingredient is a perfume on its own, but in this instance the cliché has the benefit of being true.

Vetiver oil is perfume, with its own storied and complex history. It is the scent of life and death and the earth. The smell of a hot summer, and the smell of the long grass. How lucky we are to live in a world with vetiver.

FURTHER READING

Any thoughts on Jo Malone Vetiver( discontinued) but I still have a bottle.

you need to smell Urban Scents Vetiver, she uses vetiver from La Réunion, not Haitian, it's lemony, not smokey. You'll die. https://www.urbanscents.de/en/perfume-collection/vetiver-reunion