Camellia Katabasis: Perfume at Chasing Scents

Five scents from an Australian artisanal perfumery that focuses on tea

This is the third in the House Overview series, which explores individual perfume houses in depth.

In the 19th century the East India Trading Company sought to gain a foothold in trade with the Qing Dynasty in China. Though the Chinese had many goods that European markets desired, the only resource the Chinese needed and could not supply on their own was silver, which was the form in which imperial taxes were paid.

Trading silver being not trade at all and simply buying goods for currency, the East India Company sought to create a new, artificial demand for product. The British began to flood Chinese port cities with opium, an addictive drug they planted and harvested in their colony of Bengal.

In Bengal, the disruption of using land to grow opium instead of food contributed to widespread famine and death. In China the opium poured through society like acid, corroding centuries old social structures as it went. The silver flowed back out of China and into the East India company's ledgers; the illegal trade in opium started a series of wars that would end in the British annexing Hong Kong and establishing a permanent presence in East Asia.

The East India Company had sought out Chinese trade to supply the luxury markets back in Europe, who craved produce only found in East Asia and goods made by Chinese artisans: rhubarb and cassia, nankeen cloth and carpentry, lacquerware and handmade fans, Coromandel screens and porcelain. But the British craved one thing above all others, worth any cost, worth killing for and dying for:

They wanted tea.

PART ONE: BREW

The tea plant, camellia sinensis, is thought to originate on the border of what is now Assam, Myanmar, and Southern China. It has been consumed in Asia for thousands of years, and spread to the rest of the world slowly through trade and then quickly through colonialism.

The various stages of the tea plant’s oxidation, from green to black, give us the majority of tea types you'll find in stores today. Humanity has been plucking plants and infusing them in water for thousands of years, which also gives us many drinks named ‘tea’ that contain no tea leaves but are infused in a similar fashion such as peppermint, chamomile, and hibiscus. These are often called tisanes or herbal tea to differentiate them from blends that contain camellia sinensis.

Humans have an interesting relationship with what we consume. For food and water, this relationship is about sustenance, but for everything else it’s different: we drink coffee and alcohol and tea for pleasure, for oblivion, for religious or ritualistic reasons. Of all these drinks, tea is by the most popular: after water, it is the most consumed drink on earth.

Tea parties and tea ceremonies, breakfast tea and afternoon tea, tea rooms and tea houses - for many people in the world tea is comfort and companion, part of the fabric of their lives. Tea may just be the most commonly loved aroma in the world.

The act of brewing tea is to take dead leaves and rehydrate them to create something new. In this it has a deep connection with perfume, which is transformative in the same way and often uses the same raw ingredients.

As a material in perfume, tea has nearly endless potential. Black tea, for example, can smell green or bitter, smoky or delicately flowery, or all four at the same time; its olfactory profile is complex and therefore incredibly versatile.

Whereas coffee is, in my opinion, is not possible to translate into perfumery in any successful way, there are many notable perfumes that succeed in translating tea into olfaction.

The first great tea perfume was Eau Parfumee au The Vert (Bulgari, 1992) created by Jean-Claude Ellena, who excels at the kind of barely-there delicate perfumes in which a dainty tea note can shine. This blueprint was quickly expanded on with more tea delicate scents from Bulgari and then Green Tea (Elizabeth Arden, 1999), which has spawned a frankly stunning amount of flankers over the past 25 years.

The first great experimental tea fragrance was Black (Bulgari, 1998) from Annick Menardo, and paired tea with a burning rubber and leather - it shouldn’t work, but it does, and the result is still one of the best tea perfumes on the market.

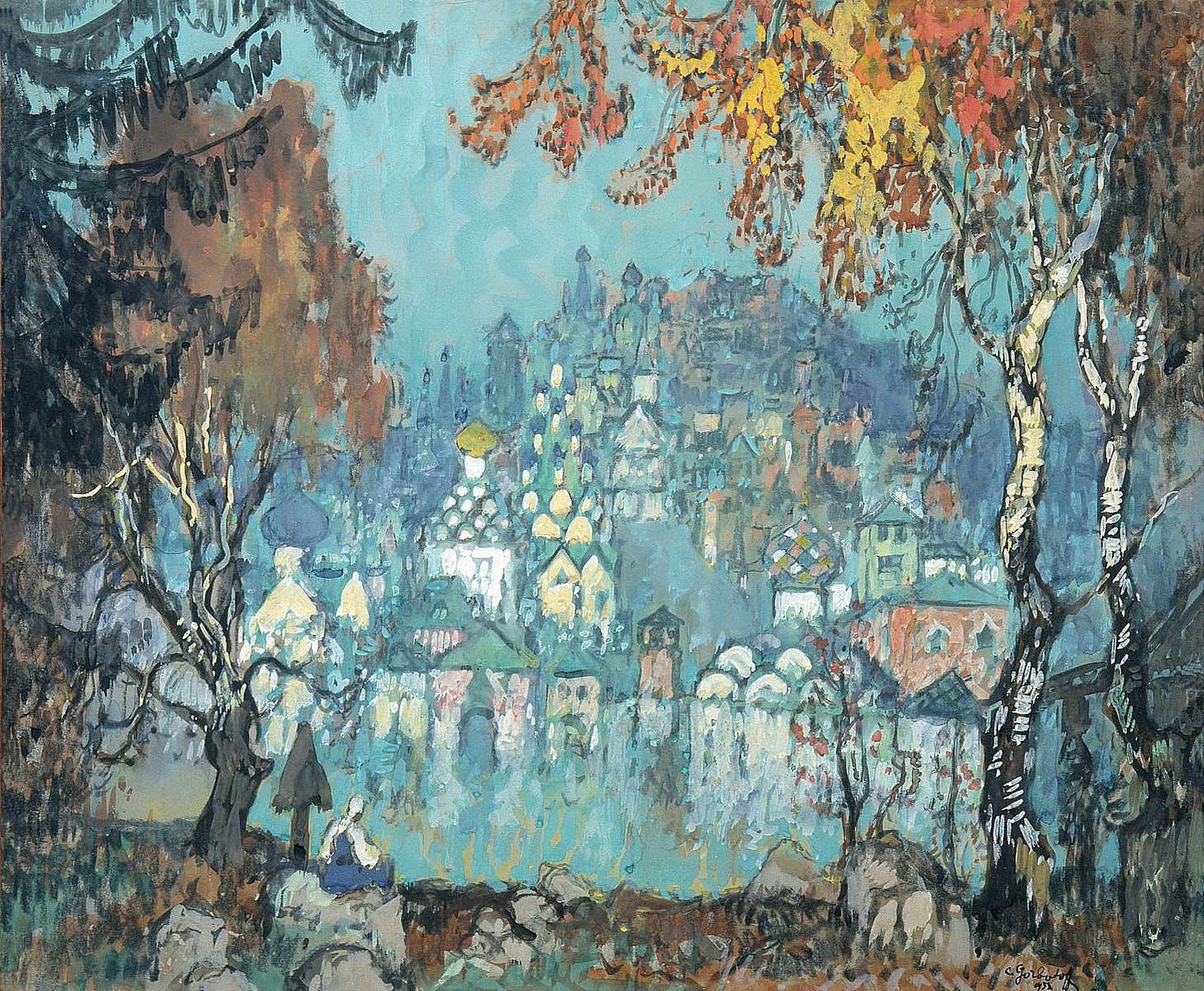

Though tea is mostly used in perfume for its floral, bright, and delicate qualities instead of its bitter and tannic facets, there are many perfumes that explore the entire range of the note’s potential. The spicy and complex Tea for Two (L’Artisan Parfumer, 2000) gives us sharp black tea with speculoos; the smoky and luxurious Russian Tea (Masque Milano, 2014) combines leather and tea to evoke a Russian caravan; and the dry and spiky The Noir 29 (Le Labo, 2014) is a sharp, cedary blend of black tea and figs.

What is missing from the realm of great tea perfumes is hyperrealism, and this is what independent Australian perfume house Chasing Scents seeks to provide.

In terms of independent perfume houses, Chasing Scents has had a meteoric rise since opening in 2021. In the short few years of its life Chasing Scents has won awards, gotten rave reviews from perfume aficionados, and scored a stockist affiliations with LuckyScent, the industry’s heavyweight for launching artisan brands.

The house is owned and run by Sandy Wong, who completed a PHD in chemistry and then decided to delve into perfume. It is based in Australia, and is one of a handful of up-and-coming Australian houses that are forming the beginnings of a genuine perfume culture on the continent (to the joy of both my wallet and my nose).

After a quality product the most important thing for a perfume brand to have is a hook, and for Chasing Scents this is as elegant as it is simple: they make perfumes based on tea. Or, as the website phrases it, “the perfumes are inspired by a personal interpretation of conversations and bonding over tea with loved ones”.

It’s a good hook, but there are plenty of tea perfumes out there and many of them are pretty good - what sets Chasing Scents apart? That is explained on the brand’s website:

“Real tea extracts made in-house are used to enhance the tea aroma of Chasing Scents perfumes. Tinctures and soxhlet extraction of dried whole flower buds and loose tea leaves are performed over multiple cycles under strict conditions to obtain an aromatic concentrate.”

I have smelled a lot of perfume and I’ve read a lot of brand copy, and before Chasing Scents I have never encountered a claim like this. It was the lure of self distilled extracts that finally persuaded me to order the brand’s discovery set.

The majority of indie perfume house creations smell like someone’s back shed experimentations with essential oils. There is a rough charm to this sort of perfumery - it sells in droves in little dabber bottles on Etsy - but they don’t feel like modern perfume as we know it. Ordering from a small batch indie house is like prospecting for gold: to find the goods you’ve got to sift through a lot of soil. The joy, as always, is in the smelling.

I was nervous as I tracked the Chasing Scents discovery set’s postal journey to my house for another reason. Tea, I must admit, has long been baffling to me. I love coffee - I understand coffee - but tea I have never warmed to. I love matcha, but black tea has always seemed to me to be a sad sort of thing, the drinking of it when it’s hot and watery a bizarre form of self flagellation.

In order to write this article I bought many different kinds of tea, smelled them and brewed them and drank them. I tried to understand the appeal of this drink, and the ritual of it, in order to better understand why we bring this scent and flavour into our lives; spend money on it; fight wars over it; make perfumes from it.

I brew and I drink; I spray and I smell. And so begins the journey into Chasing Scents.

PART TWO: STEEP

RAIN TEA (2023)

NOTES: Chrysanthemum, wattle, chamomile, white tea, rain, barley, honey, longan

As the camellia sinensis is a plant, it makes sense that most tea perfumes are florals. Complex and delicate florals, yes, but florals nonetheless. The structure of a bright citrus opening, floral heart, and musky drydown is a simple and effective framework in which to make whatever point the perfumer is aiming for within the central thesis of tea.

With Rain Tea, Wong attempts the most difficult route possible to this destination by centering her perfume around chamomile and wattle.

There’s sometimes a fine line between floral and herbal scents in perfumery. Lavender is a flower but has a herbal olfactive profile; immortelle is a floral that smells herbaceous and bitter. Chamomile is one of these ambiguous notes that contains many facets, which perfumers may bring forward into prominence or push back into obscurity like an musician changing pitch.

Chamomile is a dry and dusty sort of smell that has always made me think of old attics where light shines in through lines in the windows, warming the wood and shining patterns in the dust.

Drinking chamomile tea is a scratchy affair, and there is a medicinal bite in the background of both the taste and the scent that I am told many find calming. I, personally, found it fascinating to learn as I drank my cup of chamomile tea that there could be something that tastes the way cardboard looks.

Chamomile perfumes are hard to create and harder to sell. Though it’s an important component of Aromatics Elixir (Clinique, 1971) the most notable perfume centered on chamomile is easily Mémoire d’une Odeur (Gucci, 2019) which many loved and I hated (though I thought its bottle quite lovely), and it has already been discontinued in many parts of the world. The note’s appeal in perfume is the same as in tea, where it seeks to provide a sense of calm and relaxation.

Calm and comfort are Wong’s goals with Rain Tea. Its description reads: “A calming fragrance to soothe our heart's desire for a warm cup of tea when it rains... Soft raindrops upon the foliage of the freshly bloomed wattle trees, adrift with the gentle breeze - melding with the scent of our herbal tea.”

From the name and the notes list I am expecting a petrichor note when I first spray Rain Tea, but am surprised to sniff nothing of the kind - this is an incredibly dry perfume. So dry, in fact, that my expectations of a watery and quiet tea scent are thrown out immediately: this is a forcefully strong, dusty floral.

As I find chamomile to be a very dust in the attic kind of smell this doesn’t surprise me, but the intensity of the scent does: it’s difficult to create a perfume that feels this full bodied while also being so parched. Wong is not interested in attempting to evoke a living flower but instead makes the dried, preserved nature of drinking tea this perfume’s strongest element.

There’s a magic to this, the ability to dry living materials and then extract them into liquid form but still retain that dehydrated smell. This dryness is reinforced by a strong hay note which gives the whole scent a very sepia toned feel, as if it has been hued in shades of wheat and honey and straw.

It’s about an hour in to Rain Tea that I realise that this is not a chamomile perfume or even a tea perfume but actually a mimosa perfume. Though the tea notes are legible in the scent, everything is playing second chair to a hell of a golden wattle that shines from the heart of this perfume like a sunrise piercing through the trees in a forest. This note is so powerful and so moving that when I lift my nose from exploring the drydown the only conclusion I can come to is this:

Rain Tea is a perfume that smells like Australia.

Her beauty and her terror - it’s hard to explain to anyone who doesn’t live in Australia that our dry is different from other places; that underneath the Wallace Line the world spins differently and the wind is full of dust.

The brittle crunch of turning pages in an old book, the scratched bare feeling on the insides of your cheeks when you’re desperate for water - that’s what the air in Australia feels like. That’s the smell of eucalyptus and golden wattle and gum trees.

On this continent there’s not enough water, anywhere, and the result is a hardiness in the soil and in the plants and in the bark. Australian native plants have a thick, dusty, almost fibrous smell, like they’ve endured things and are prepared to endure more. There is a deep beauty to this. The dusty, pollenated, powder-dry smell of golden wattle spreads across the wallpaper of my childhood; where I live it grows in abundance on train lines, and the smell always makes me think of springtime, journeys to the city, the oncoming threat of summer bushfires. It’s a smell very similar to mimosa, but with an underlayer of dried bark and the bitter bite of tannin.

The natural materials used in Rain Tea have recreated the scent of golden wattle to an almost eerie accuracy. I was utterly transported smelling this perfume, which is abstract enough to not smell synthetic or manmade - it genuinely smells as if someone went outside, cut off a branch of wattle, and bottled it immediately. How unexpected and how wonderful to find a sliver of the world inside a bottle of perfume.

Rain Tea is quietly forceful - it lasts all day on my skin and weeks on the blotter. This must be from the natural tea extracts Wong infuses, because I’ve never smelled floral perfumes with a half life as strong as the Chasing Scents set. I left my Rain Tea tester in my dressing room and would occasionally walk in and wonder if I had left a bouquet of native flowers in there to dry out.

To an Australian I would say that Rain Tea will be written on their bones as legibly as a Bunnings sausage sizzle or hearing Flame Trees on the radio or afternoons spent swinging from your grandmother’s hills hoist. You know this smell and it knows you. To anyone else I would say that if you are a lover of a mimosa or interested in a perfume that seeks to find a beauty in great harshness, get your nose across Rain Tea and be transported for a moment to Sydney when springtime is in bloom.

SLOW WORLD (2021)

NOTES: Pu’er tea, saffron, dragon’s blood resin, malt, sandalwood, vanilla bean, incense

In most perfume house line-ups there will be lighter fare, colognes and citruses and delicate florals, and then there will be the heavy hitters: dark ouds or smoky ambers, deep leathers and dense gourmands.

Colour is often the first signifier of this delineation, either in the liquid itself or in the packaging, and I could see immediately from the rich russet red of this perfume that Slow World is Chasing Scents’ heavyweight.

The tea component in Slow World is pu’er, a fermented tea that has a strong and slightly funky aroma, similar to other fermented products like soy sauce or kombucha. Your nose can tell that there’s something a little odd going with fermentation, but once you become accustomed to it that oddness become a scent that you crave.

The problem with reading a note list that contains something like pu’er before smelling the perfume is that you go hunting on the blotter: an expectation has been set and if the answers aren’t to your satisfaction, the entire perfume is a wash.

The rich ochre-red promise of Slow World translates to a delightfully russet spray on the blotter. There is no waiting to let the alcohol dissipate before bringing the blotter up to your nose: this perfume is racing out of the bottle to knock you about the head. There is certainly a tea note kicking around in the background here, but the rest of the perfume is overshadowing it with an intense and powdery saffron-amber.

There are countless amber perfumes in the world, and Slow World is a pretty good one when measured against the rest. It’s rough, almost coarse in texture, the saffron and the sandalwood jagged and spiky as if they’ve been scraped over with sandpaper. But this is to its credit - there is a place for sophisticated ambers and there’s a place for their punk rock cousins too.

The make it or break it element of a modern amber is always in its sweetness, and though there’s a vanilla note here it is not saccharine. Though lost in its clarity as a tea perfume, the pu’er tea note helps to make Slow World a unique amber, more than the sum of its parts. There’s a powdery, faded bitterness to this scent that grows as the perfume fades, and it does indeed become something you start hunting for earlier and earlier each time you spray as you acclimate to it.

As the perfume moves to the drydown, it is overwhelmed by a smoky and somewhat dirty incense. The incredible versatility of incense is that unburned it has a clinical scent, the smell that was so pure and unearthly that it was natural for the ancient world to believe it was an offering to the gods. When burned it comes a little more down to earth with a smoky, charred, almost barbecued facet we always associate with things on fire.

Slow World’s incence is the chewier, earthier second kind, which plays well with its warm amber and dark pu’er notes. I do wonder as I smell it if the scent couldn’t have benefited from that cleaner, harsher incense, to counteract all the indulgence of this almost gourmand perfume rather than adding to its lush feel.

If a delicate tea perfume is like a classic brew with no additives, tinged yellow or amber but still translucent, then Slow World is a boba tea or a London Fog, where your focus is on all the moving parts and not just the tea flavour.

This is the perfume of the Chasing Scents set that feels least tea-like. If you follow Chasing Scents on social media you will know Wong will occasionally mention an interest in creating perfumes inspired by coffee, and Slow World feels like a step in the direction of a scent construction that would work well with a coffee note.

I remain a great sceptic about the possibility of ever creating a good coffee perfume - but I’m beginning to think that if there was ever a perfumer who could capture the scent of espresso, it might just be this one.

WEEPING ROSE (2021)

NOTES: Rose bud tea, red apple, juniper berry, fig leaf, orris root, maple, amber, vanilla bean

Though rose is too ubiquitous and too beautiful to ever fall out of use in perfumery, the rose soliflore is definitely out of current fashion. If your rose smells too much like a rose, you risk the perfume getting the fragrance equivalent of the scarlet letter: it will be called an old lady perfume.

Cultural perceptions around women and aging are too many to tackle through the lens of any perfume, no matter how complex, but nonetheless this is a very real part of the culture of fragrance. There’s a pejorative attached to smelling like something your grandmother would wear, as if by spraying them you are reminding yourself and everyone around you that you, too, shall someday die.

Towards aging and towards rose perfumes I have a different mindset: I think both are incredibly beautiful. I think that they’re a gift. I think that there’s something lovely about smelling a perfume and being reminded of your grandmother or an earlier time, a younger world - that perfume can be a living thread between the past and the present.

One of the best rose perfumes on Earth is the aptly named Tea Rose (Perfumer’s Workshop, 1977), which can be bought for $14.99 at your local chemist. A nearly perfect rose soliflore, it captures a rose in the the prime of its life; stem still green and petals covered in dew. In smelling it you can smell every rose that has followed after it, including this one from Chasing Scents.

Weeping Rose is an old lady perfume and that is what is loveliest about it. Its old fashioned, dusty rose comes tumbling out of the sprayer immediately. On smelling it my mind jumped straight to Tea Rose, old fashioned perfumes, hard boiled rose candies, and soap wrapped in vintage paper.

It’s been such a long time since I’ve smelled a rose that isn’t deconstructed of its powdery, soapy, unfashionable elements that smelling Weeping Rose felt like saying hello to an old friend.

Though its rose note has a beautifully old fashioned feel, like a painting by Alphonse Mucha, the scent subverts this by using a sharp apple accord in the opening to cut through the pastel hues. The scent follows Rain Tea’s lead by being delightfully abstract so that the notes list becomes almost irrelevant, even though the sharp fruity opening and floral heart almost veers towards a chypre structure. You can’t pull out a maple leaf or an orris or a vanilla here, only different dimensions and shades of that rose, that Billie Holiday soundtracked rose, that beautifully complicated old lady smell.

There’s a daintiness to Weeping Rose that makes me think of white gloves and fine china teacups and women wearing fancy hats. But there’s also something sharp here, a little barbed, as sweetly vicious as the gossip that always accompanies a really good afternoon tea. I’m not sure why this rose is Weeping, but I think it might be from laughing so hard that tears form - this is a perfume with the well earned grooves of crow’s feet and smile lines.

Weeping Rose is the Chasing Scents perfume that conveys the brand’s ethos of ‘personal interpretations of conversations and bonding over tea with loved ones’ best for me - this is a perfume that smells like women talking. The perfume has a soft but persistent sillage, the rose and apple given longevity from a handful of notes that should skew gourmand but never get sweet enough, so the result is instead a wonderfully multidimensional rose. This is the smell of the kind of conversations you have when there are women from multiple generations at the table, eating together, laughing together, sharing their lives together.

The natural tinctures Wong is putting in her perfumes are so evocative that smelling them is almost painful - but it’s the good pain, the kind that’s followed by a soothing touch and a fading bruise. There is an unspoken (and sometimes challenged) rule in perfumery that besides gourmands, people don’t really want to smell like what they eat. I have always felt that this was because there is an unpleasantness to smelling food once you’re done eating it, but Weeping Rose and the other Chasing Scents perfumes make me think that taking these scents, the food we eat and the drink we drink, and turning them into art is to cast a lens on our own lives that is so monumental it threatens to overwhelm us.

I never knew I remembered the feeling of sitting around a table scattered with empty mugs of coffee and cups of tea while I laughed with a group of women over something ridiculous; I never knew that I remembered the sillage that hovered around us, our different perfumes mixing together like a veil between us and the rest of the world. It’s there in this perfume, this unremembered memory, living in its chameleon rose that is old and young and harsh and soft all at once.

How could you not remember something and yet cherish it so deeply at the same time?

I find myself reaching for Weeping Rose more than I ever thought I would because I want to bask in that memory. I wear it and I smell like an old lady, and it is so beautiful, and I think about the gifts of perfume and of time.

PRIVATE TEAHOUSE (2024)

NOTES: Peach, cacao, smoke, lapsang souchong tea, cedarwood, labdanum, peach sap

If you have even a passing interest in fragrance you will end up smelling hundreds of leather perfumes in your life. Pump enough smoke and birch tar into a perfume and it won’t smell like anything but a barbecue. Private Teahouse is one of these scents.

It would be disingenuous to say that this perfume opens with anything but the tarred, smoked, beaten leather that lives at its heart. But it’s the peach note that fades fastest so that’s the one we will discuss first. It takes a minute or ten to get your nose used to the leather in Private Teahouse but once you do the peach becomes clearly legible, way down there in the footnotes.

As a fruit note I really like peach. Its plush, lactonic scent always makes me think of Mitsouko (Guerlain, 1919) and can be tart or powdery or slightly leathery, a characteristic all stone fruits share.

Private Teahouse’s peach reminds me of peach flavoured sour candy, the kind that’s ridged in citric acid and makes your mouth pucker. That’s exactly how I like my peach candy, so I’m pleased to find such a realistic smelling note buried in this leather-and-tar perfume. The lactones that are typically used to create a peach accord give this perfume a velvety, well rounded feeling. It’s always so refreshing to smell a fruit note that’s not half heartedly cheerleading at the top of a saccharine gourmand.

This is an intelligent, thoughtful interpretation of peach buried in the heart of what is named as a tea perfume but is actually a leather perfume. But then everybody likes peach tea, don’t they? And if this really is the smell of a private teahouse, it’s not a stretch to imagine the scent of different tea mingling in the air. This imagined geography is deepened when one pictures a room with lacquered walls and wooden furniture, a place you duck into on a cold morning for a warm drink - that’s the smell of Private Teahouse all over.

This effect is achieved by a leather accord that on the surface appears traditional but has a lot of interesting parts moving under the hood. On first spray of Private Teahouse my mind immediately jumped to Tom of Finland (Etat Libre d’Orange, 2007), a brilliant leather and saffron scent. Both perfumes take their leathers in a medicinal direction - Finland using saffron and Teahouse using labdanum - that gives the scents a satisfying bite.

All great perfumes should have something a little bit wrong about them, a thread that the human nose recognises as not right. Private Teahouse does this by smelling like peach cough syrup being poured into your mouth by a hand wearing a dark leather glove, and by coincidence it’s happening in a tearoom.

As someone who likes cough syrup, rough leather, and wood polish, all of this combines into a turpenic brew that makes me wince and then makes me smile. What’s missing in all the funk is a clearly discernible tea note, but I don’t think that’s the purpose of the perfume.

Anyone who has smelled or tasted lapsang souchong knows that there is a strong smoky flavour to it - it has an aftertaste that can, in its most dire moments, taste of sizzling bacon - and that smoke is lingering all over Private Teahouse.

The tea I’m most familiar with with a smoky note is Russian Caravan, which has lapsang souchong in the blend. The smoky flavour of the lapsang is traditionally attributed to the tea’s exposure to campfires on the overland journey between China and Russia. The aesthetics of this tea has a strong crossover with perfume, in which there is a grand Russian leather tradition that goes back centuries.

One of the primary materials used to create a leather accord is birch tar, which was used on Russian leather exports to preserve them from infestation. Russian leather and Russian caravan have the same story, which is how long journeys can change you; the transformation is contained in the smell.

Private Teahouse is not a birch tar leather - perhaps this is something Wong will work on in the future - but there is a woodiness to its drydown, the smoke and the leather trapping that transformation of raw to final form. In fact it’s a little claustrophobic, this perfume. The image it conjures for me is not the open skies of a journey but small wooden boxes with treasures kept inside them. There’s a feeling inside this scent of a frozen moment, of still air.

It’s only after smelling it for hours that I come to a realisation: Private Teahouse is a leather perfume, but it’s not an animalic perfume. There’s no castoreum or civet or any of the typically thick notes perfumers use to enhance and deepen a leather accord - there’s no musk here, no skin; at the heart of this perfume there’s no animal and there is no human.

It’s a brave choice that takes the perfume in a noticeably synthetic direction. On the Chasing Scents website, Private Teahouse is described as “a warm invitation to the fragrant sanctuary separate from the daily world”. And this it certainly is - this is what perfume, and perhaps the world, smells like when you take out all the people and only stillness remains.

It’s an odd thing to smell, seeing as you are a person smelling it, and you feel like perhaps you’re sullying the whole thing - adding humanity back to the center of a story where it doesn’t belong. Private Teahouse is indeed private - it is keeping its secrets from even its wearer.

What a strange and interesting thing, to feel like a transgressor into the private and scented world of a perfume. I find a strange beauty in my distance from Private Teahouse, as if I have watched a film in another language - I have seen it, and I enjoyed it, but I know that something in translation has been lost and there are things it has said that I am not meant to understand.

TEA SERVICE (2021)

NOTES: Jasmine, oolong tea, goji berry, osmanthus absolute, white peach, musk

There are many flavours, motifs, and feelings it is difficult to accomplish through the medium of scent. A realistic coffee accord, as I have mentioned before, is one of them; reconstructing the scent of flowers that cannot be harvested for fragrance, like lily of the valley or gardenia, is another. I believe a third type of perfume that is difficult to create is one that conveys the sense of translucency, of gossamer weightlessness, that we associate with water.

There are two types of perfumery that try to convey a feeling of water: the genre of blue-bottled beach themed scents we call aquatics, and a handful of bilge water nightmare perfumes that to try convey a sense of the deep ocean that I like to call marine perfumes. Both are terrible in their own unique ways, and neither genre has ever effectively given an impression of water, artistically or otherwise. Water is like sugar and salt -that is to say it is a taste and not a scent - and that makes it incredibly hard to convey in a perfume.

Water is also half of the story when it comes to tea as humans consume it. The ethos of Chasing Scents is to convey tea through perfume, but specifically drinking tea, not simply the living plant or the dried leaves. Water, milk, or any other substance that tea is steeped in gives tea a body, a weight, a new shape - it is transformative. You could argue that a tea perfume that cannot convey this is missing its core purpose entirely.

Anyone who has been hypnotised by the lull of a wave meeting a beach shore can understand why water has been used as a motif for transformation for thousands of years. Mermaids and selkies and kelpies, the sinking of Atlantis and the great wave of Kanagawa, voyages and baptisms and drownings: you go into the water and you transform. You go into the water and what comes out is not the same.

Tea Service is the first release from Chasing Scents, and as a perfume it is inarguably their most technically competent. On its face a jasmine and osmanthus floral, this scent is the only perfume I have smelled from any brand that somehow conveys the scent of tea and the feeling of the water it is steeped in.

The tannic, dry black tea accord that may well be Chasing Scents’ version of a Guerlinade is here from the first spray. In Tea Service it is playing harmony with a radiant jasmine that has been given the same dried, dusty treatment as Weeping Rose - it smells like a jasmine that has been lovingly pressed between two pages of a book.

There’s nothing indolic here - in fact, there’s so little that is customarily floral about the floral notes from Chasing Scents. They are less like a real flower - or even the attempt to recreate a real flower - and more like those 19th century botanical paintings of flowers, realistic and comprehensive and yet so completely their own creation, a flower preserved in paper and ink.

Both jasmine and osmanthus have a reassuring softness in Tea Service, playing against the bitterness of the black tea. Yet even that is not too urgent or punchy, because the entire perfume is buffeted and cast with a gossamer sheen from a radiant musk note that seems to want nothing more than to enhance everyone else’s beauty, like the people who stage lighting at the theatre. Radiance, that what’s the musk in Tea Service brings - what a white musk should always bring to a perfume when it’s used with a deft hand.

Like the best perfumes I can see the moving parts of Tea Service, osmanthus and jasmine and tea and peach, but these all diffuse together at the edges into something more abstract, into a scent that is entirely its own, a novel creation. There’s a greenness at the beginning that moves and flows into a rounded floralcy that is somehow both a traditional perfume and not, because the natural materials are complicating and muddying everything.

Tea Service does not smell wet and yet it nonetheless smells watery, as if all the materials have been submerged in the mineral-tinged bite of a mountain spring. It is incredible; I find myself marvelling at the blotter, wondering what’s the trick? The balance of the natural materials with the musk? The extracts themselves, somehow conveying a weightlessness to what are typically quite dense olfactive notes like jasmine and musk? Or is it simply my own brain firing up, making connections, saying I know this smell, I know this taste?

It’s there, the water. I can feel it in the peaks and troughs of this perfume, in the webbing and the structure that brings all the parts together in symphony.

I think there’s something deep in the human psyche that craves the ocean. We know, on a biological level, that we came from the water and we feel an urge to return; or maybe the sensation of being underwater, both weighted down and weightless, is the closest we can find to a womb.

When Batu Khan and the Golde Horde swept through Russia in the 13th century, there’s a legend that the people in a city called Kitezh prayed for salvation from the invaders. The legend says that a thousand fountains burst forth and pulled Kitezh to the bottom of Lake Svetloyar, where it remains to this day; sometimes people claim that they can hear the bells from the city chiming, or the chant of a procession in song.

They prayed for a miracle and the city flooded; the water surrounded them, protected them; the water kept them safe.

When the world is burning down around you I suppose there’s solace in thinking that somewhere there is a part of it that isn’t broken. Submerged in the water the people of Kitezh will live forever, frozen in time and yet eternal because the people above need to remember them that way.

Tea Service surrounded me in a feather light halo for an entire day as it dried down, and I tried to puzzle out why it had summoned up the memory of Kitezh. There are more than enough stories that are waterlogged, after all - Titanic, Atlantis, Virginia Woolf and John the Baptist, the climate crisis, flood narratives the world over. Water is the one universal, the beat in every mythology, the only thing that’s equally important to all of us.

It was the third or fourth time that I wore Tea Service that I could finally name the feeling that connected its radiant tea and flowers blooming in water scent and the image of a villager leaning over the edge of a lake to catch a glimpse of the cathedral peaks in Kitezh and hear the chime of its unbroken bells.

Peace.

It was peace.

PART THREE: DRINK

I’ve always liked that tea is sold in little boxes.

When I go to the tea aisle in the supermarket, it’s usually to grab a box of matcha and then move on to the coffee. But every so often I linger; the tea is so strong that you can smell it even from the other side of the aisle, like a wall of tannins wafting out at you, and they look so perfect all lined up together in their colourful little boxes, the brands that you can’t remember when you first heard of because you’ve just sort of known them all your life: Lipton, Tetley, Twinings.

The Englishness of the boxes holding a very un-English thing feels so pointed, a thorny history boiled down to a little boxes of vanilla chai and Assam bold.

Understanding tea is a hurdle I’ve never been able to cross. But to write this article there was no choice but to delve into this infused world. I bought the little boxes and began my own journey: I drank tea cold and hot and lukewarm, with sugar and milk and lemon, green and black and oolong, peppermint and chamomile and Earl Grey.

My body, used to its one coffee in the morning and one in the afternoon, did not handle the extra caffeine well; I have spent many weeks in a state of leg-twitching jitteriness as I have written this article. Its completion will be of deep relief to my nervous system.

What shocked me most during my camellia katabasis was the the dryness of tea, as opposed to the round fullness of coffee or a sweetened drink. It’s not a pleasant sensation but there is something satisfying about the unpleasantness of it; the bitter tannins hitting your tongue satisfies the part of your brain that craves the ache of pressing on a bruise.

It’s how you know you’re alive, I think - the pains that are big enough to notice but too small to harm.

The tea I liked best was iced black tea, brewed strong and with no additives. The great appeal of coffee is that you taste it most on the back of the palate, but I found tea to be the opposite - you are hit with all its flavours immediately and then there is little to no lingering taste, only that feeling of dryness.

The gossamer thinness of the tea was not a flaw but an attribute: I felt like I could drink about five cups of the stuff. I began to appreciate its bitter herbaceousness, its harsh dryness, that ghostly touch of floralcy. I began to understand why every culture in the world is obsessed with tea.

We have a different relationship to flavour than we do to scent. The two are closely intertwined but discrete, brothers but not twins. I think that part of what gives scents like Weeping Rose and Tea Service such a heavy impact is that they are engaging both scent and taste, that place at the back of your nose where the two intertwine, so that in smelling them your brain lights up lights a firework. There’s a feeling of consumption when you smell these perfumes, like a hunger you didn’t realise you had is being sated.

Humans are hardwired to experiment, to test their surroundings, and I can only conclude that’s how we ended up picking leaves off the camellia sinensis, drying them, boiling them, and steeping them into tea. Perhaps it was only a matter of time until someone extracted tea into the potent materials that can be smelled in the perfumes from Chasing Scents.

But raw materials alone do not equal good perfumes, and the five perfumes from this brand showcase a talent in Sandy Wong that deserves all the accolades she has received and more. The fact that perfumes of this quality are available for $150AUD is an embarrassment to perfumes that are thrice the price and half the quality.

Like the aisle at the supermarket, like a cupboard full to the brim with little boxes, a Chasing Scents perfume will scent the air for weeks and weeks if left unattended. Blotters that I sprayed simply didn’t give up, the natural extracts so prominent that I decided to capitalise on the situation and put them in my sock drawers. My ankles have gently wafted the aroma of lapsang souchong ever since.

Across every Chasing Scents perfume description and instagram post there is one common theme: introspection, reflection, a sense of contemplation and peace. I can understand, as I smell these perfumes and drink endless amounts of tea, why someone could find that feeling at the end of the drydown and the bottom of the teacup. I’m simply not that person: I’m the person that steeps ten bags of tea into an iced concoction that gives me heart palpitations, and smells a perfume that makes me so emotional I have to put it in time out in another room until I’ve composed myself.

But a perfume, like a person, contains multitudes. It’s a testament the quality of the materials and the scope of Wong’s talent that the Chasing Scents set are as good as they are. To understand them requires an active mind, concentration, and a sniffer who is willing to listen to what the perfumer is trying to say; to enjoy them is unavoidable and effortless.

At the end of my experiment I’ve come to the conclusion that I don’t think I’ll ever be a tea person, but I am certainly a Chasing Scents person. In fact, I’ll make it a ritual: when Sandy Wong releases a new perfume I’ll order a sample, buy a little box of tea, brew myself a cup and let my mind rest for a moment as the blotter gets dry and the steam from the mug unfurls.

Maybe the peace will come to me in time. Until then, there is nothing to do but drink the tea, smell the perfume, and surrender. ■

Beautiful essay. Thank you. But I’m going to be that guy and encourage you to give tea another shot. If you have only had tea that came in bags from the supermarket, you have only experienced the lowest quality dregs. Seek out some good quality loose leaf and a temperature specific kettle (or thermometer) for the real deal.

My show is onnnnnnn (I absolutely adore your house review series)